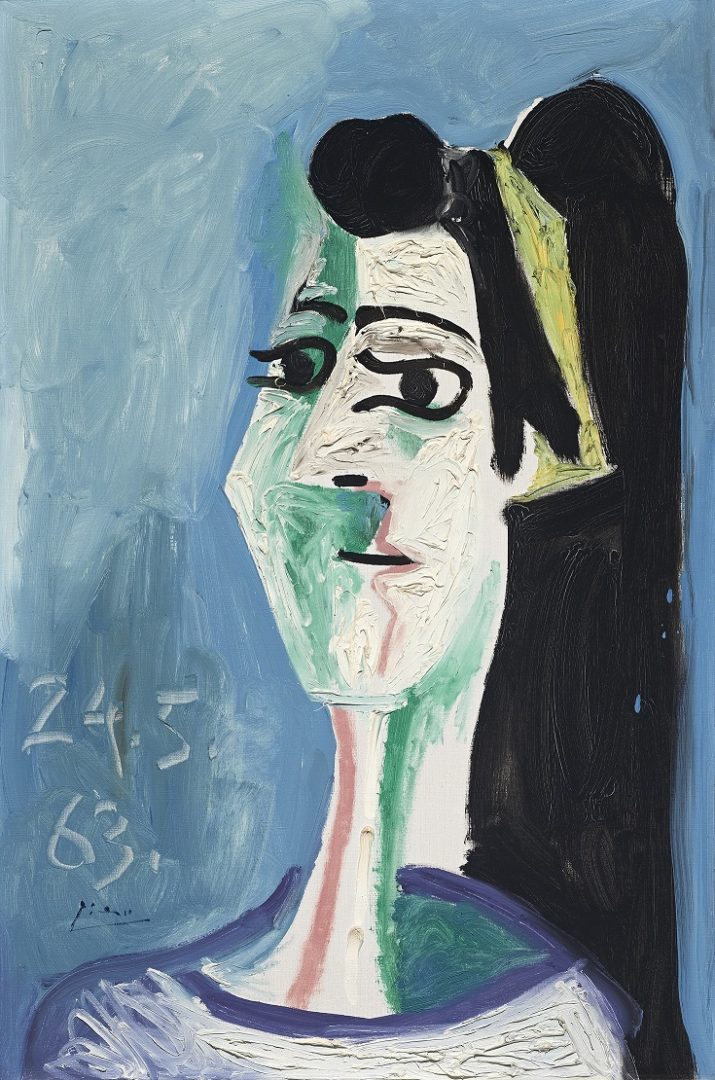

Pablo Picasso

Tête de femme, 24 May 1963

Provenance:

Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, Galerie Louise Leiris, Paris (no. 010593, ph.no.61261), acquired directly from the artist.

Berggruen & Cie., Paris, acquired from the above.

Private Collection, Switzerland, acquired from the above in 1967.

Literature:

Leiris, Picasso: Peintures 1962 – 1963, exh. cat., Galerie Louise Leiris, Paris, 1964, p. 55, no. 62.

Parmelin, Picasso: Le peintre et son modèle, New York, 1965, p. 180.

Zervos, Pablo Picasso, Oeuvres de 1962 à 1963, vol. XXIII, Paris, 1971, no. 282 (illus. p. 131).

Wofsy, The Picasso Project: Picasso’s Paintings, Watercolours, Drawings & Sculpture, A Comprehensive Illustrated Catalogue. The Sixties 1: 1960 – 1963, 28 vols., San Francisco, 2002, no. 63-164 (illus. p. 381).

Haldemann, Die Picassos sind da!: Eine Retrospektive aus Basler Sammlungen, exh. cat., Kunstmuseum, Basel, 2013.

Exhibited:

Paris, Galerie Louise Leiris, Picasso: Peintures 1962 – 1963, 15 Jan. – 15 Feb. 1964, no. 62.

Basel, Kunstmuseum Basel, Die Picassos sind da : Eine Retrospektive aus Basler Sammlungen, 17 March – 21 July 2013, no. 109.

Despite its impersonal title, Tête de femme is a portrait of Picasso’s second wife Jacqueline, his muse and constant companion during the final two decades of his life. It was painted on 24 May during a period of heightened productivity in the spring of 1963. As she is in other portraits, Jacqueline is immediately recognisable by her exaggeratedly large, dark eyes; her long black hair; and the ribbon headband she often wore.

Picasso met Jacqueline Roque sometime between the summer of 1952 and 1953 (the timeline is uncertain) in Cannes, when she was employed as a salesgirl at the Galerie Madoura, rue d’Antibes, which sold the Ramié editions of Picasso’s ceramics. She first appeared in his work in the summer of 1954. Picasso liked the fact that Jacqueline resembled a figure in one of his favourite paintings, Delacroix’s Women of Algiers, from which he had sketched in the Louvre. Jacqueline, in turn, was quickly smitten with the charismatic Picasso, and their affair eventually drove Françoise Gilot, his long-term mistress, to leave him, taking their children Paloma and Claude with her. Picasso and Jacqueline were married on 2 March 1961, several years after the death of his estranged first wife, Olga, and moved from La Californie in Cannes to Notre-Dame-de-Vie, a farmhouse just outside Mougins.

Jacqueline’s image dominates Picasso’s work from the summer of 1954 until his death nearly two decades later, twice as long as any previous inamorata. For seventeen of the twenty years they were together, she was his only model and muse. Devoted to Picasso, as well as submissive in a way the independent Françoise never was, Jacqueline was content to sit for hours in Picasso’s studio while he painted. Although she did not pose in the traditional sense, she appeared time and again in Picasso’s paintings, drawings and sculptures, in forms both realistic and abstract. Picasso found her presence calming, as well as inspiring, declaring: ‘Jacqueline possesses to an unimaginable degree the gift of turning into painting.’ She was also fiercely protective of Picasso, and did her best to shield him from the demands and obligations of fame so that he could devote all his time and energy to his art.

In Tête de femme, the 36-year-old Jacqueline – at this point Madame Picasso – appears serene, depicted bust-length against a a blue ground. Her black hair is secured with a yellow ribbon, a style she favoured, as we can see in contemporary photographs and in a sculpture executed the previous year. It is one of two portraits of Jacqueline that Picasso painted on the same day. The other, which is likewise on a blue ground, and slightly larger in dimensions, depicts the sitter frontally rather than in three-quarter profile (sold Christie’s, London, 2 Feb. 2010, lot 29.)

Tête de femme was included in the 1964 exhibition Picasso: Peintures 1962 – 1963 at Galerie Louise Leiris in Paris. The gallery was established in 1920 by Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, one of the earliest supporters of Picasso and Cubism, who opened his first gallery in Paris in 1907. Originally known as Galerie Simon after Kahnweiler’s partner, André Simon, it was renamed in 1940 when Kahnweiler’s sister-in-law Louise Leiris took over its management. The picture was then purchased by the present owner’s family in 1967 from Berggruen & Co., and it has been in this collection for half a century.

The ‘K’ inscribed on the stretcher bar indicates that this was a painting Picasso designated for Kahnweiler, much as paintings inscribed with ‘R’ were intended for the Rosengart gallery. It was Picasso’s normal practice later in his career to leave works unsigned until he intended to sell them. As the photographer David Douglas Duncan recorded, Jacqueline was always on hand to assist Picasso with these final touches: ‘She helped tirelessly, silently, on canvas-signing days, until the final “K” (Kahnweiler) was printed on works for Paris, for their journey from his studio to a future life of their own’ (D. Douglas Duncan, Goodbye Picasso, London, 1974, p. 212).