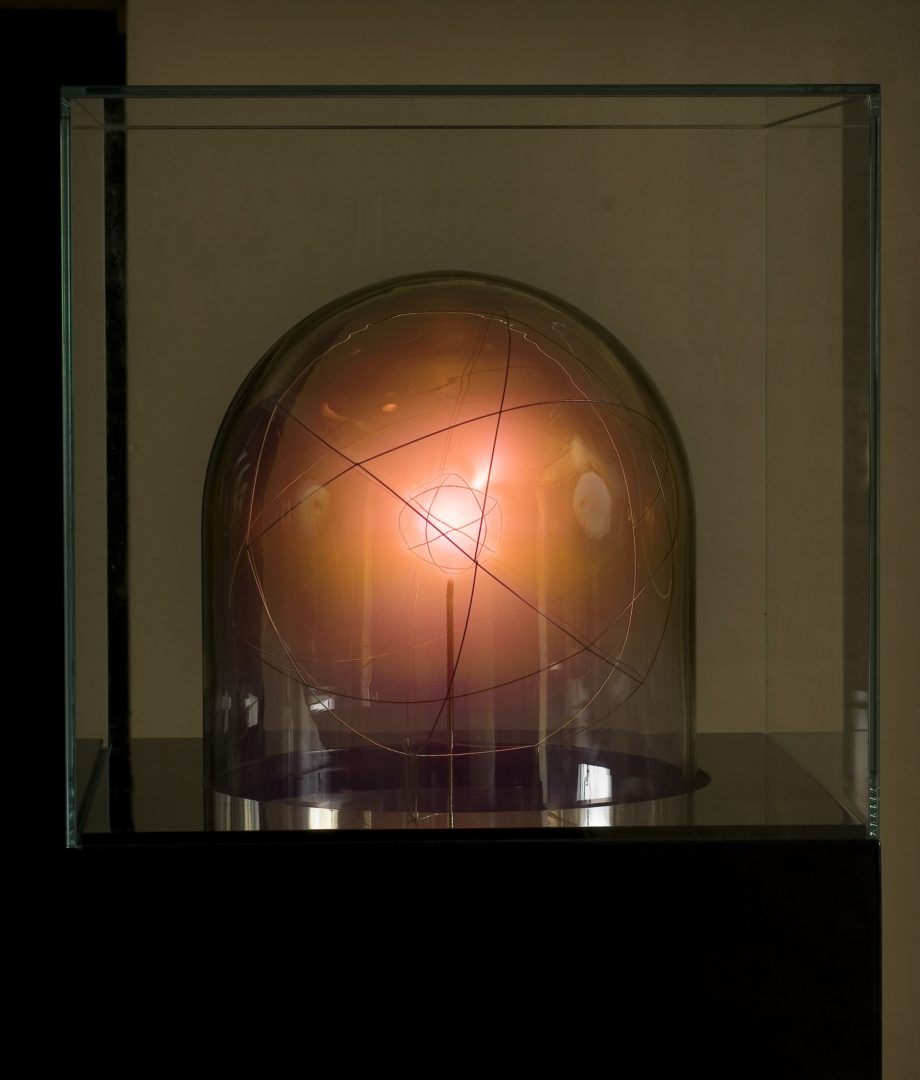

Paul Fryer

Perpetual Study in Defeat, 2006

Provenance:

Private Collection, UK.

Exhibited:

Gloucestershire, Sudeley Castle, Reconstruction 1, 1 July – 31 Oct. 2006.

London, Fire Station 1 Chiltern Street, Paul Fryer: Potential and Ground, 8 Feb. – 10 March 2007.

London, One Marylebone, The Age of the Marvellous, 14 – 22 Oct. 2009.

‘Fryer’s Perpetual Study pulsates with a luminous breathing glow. Staring into the baby star, we climb momentarily clear of the world’s edge on a vertical rainbow, peeling away the cosmos in the heart’s jam jar. It reels you into its mystery. You are involved in something you perceive as natural and supernatural at the same time, yet something assembled out of the nuts and bolts and wires of our existent world. How strange! In this way, the life-support system of science produces art’ (A. Harlech, ‘Wreathes and Nests’, in P. Fryer, Radiations, London, 2007, p. 14.) Hans Ulrich Obrist has described the hypnotic effect of the work: ‘There’s something about the rate at which the star breaths…Almost appearing to be alive…it’s […] you just get drawn in. I actually noticed after a while that I’d synchronised my breathing to the rate of the star’s breathing.’ (H. Ulrich Obrist, P. Fryer & C. Dancer, “In Conversation”, from P. Fryer, Radiations, London, 2007, p. 18.)

As Paul Fryer has explained: ‘The star in a jar is basically a simple fusion reactor in a bell jar. What you see when the machines are activated is a small sun inside a glass dome in a vacuum almost as empty as outer space. The work comprises two sets of metal hoops (or grids), one 12 inches in diameter and the other, the central grid, approximately one fifth of this. These are contained within a borosilicate glass jar, which is connected to a high-vacuum system. Then the air is pumped from the system, and the inner grid is charged to around -8kV in waves that last about seven seconds. The outer grid remains earthed, and so any residual particles of gas are accelerated at close to the speed of light towards the centre of the inner grid, where they collide and form a superheated plasma ball. This happens because there is nothing to stop them being accelerated, and the vacuum also insulates the heat, which quickly builds up due to these collisions and the accompanying shock and compression waves. Temperatures of 10,000,000˚C are easily exceeded, this being proved by the readiness with which deuterium will fuse when introduced into a system like this. It is not a thing we would normally observe from closer than 93,000,000 miles. It is a tiny nuclear furnace held in place by the mysterious forces of electrostatic confinement, a ball of incandescent elemental gas stripped of its electrons…’ (P. Fryer and C. Dancer, quoted in A. Harlech, ‘Wreathes and Nests’, in P. Fryer, Radiations, London, 2007, pp. 13-14.).

We are grateful to Paul Fryer for his assistance with the preparation of this catalogue entry.