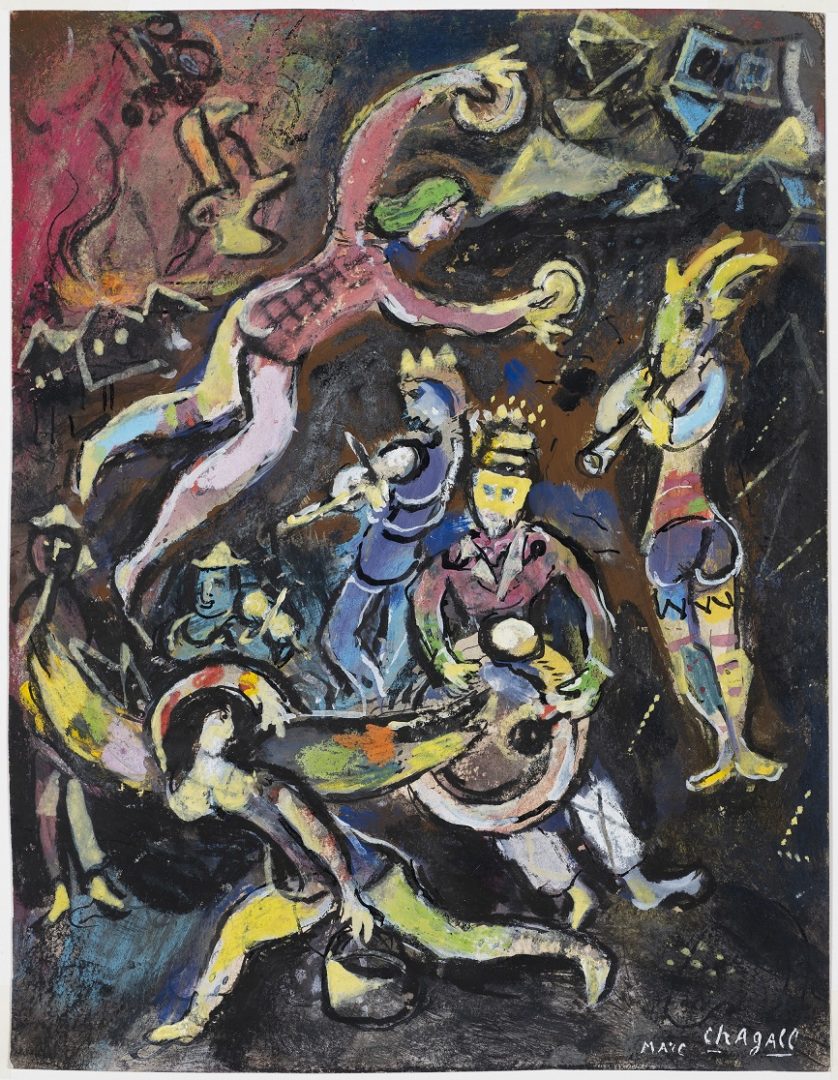

Marc Chagall

Le Cirque du Paradis, 1959-60

Provenance:

Private Collection, Switzerland.

Private Collection, Switzerland, by descent from the above.

Le Cirque du Paradis features a visionary image of Chagall’s most iconic motif: the circus. The spectacle of the circus and its performers had fascinated Chagall from his childhood days in Vitebsk, Russia, where travelling acrobats and equestrians often came to entertain crowds at village fairs. With time, the circus came to lie at the very heart of his personal mythology. In his art, he summoned the spectacle of the experience in all its colourful variety as a vivid metaphor for the life he had decided to lead. As he wrote in 1967: ‘For me a circus is a magic show that appears and disappears like a world. A circus is disturbing. It is profound…It is a magic word, circus, a timeless dancing game where tears and smiles, the play of arms and legs take the form of a great art.’ (‘Le Cirque’, 1967, in P. Southgate, trans., Le Cirque: Circus Paintings, exh. cat., Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York, 1981, n.p.)

In Le Cirque du Paradis Chagall combines human and fantastical figures in powerful primary colours, floating against a dream-like black background. A daring trapeze artist floats freely above her fellow circus performers as they play musical instruments: on the violin, a woman painted head to foot in purple, and accompanying her on the clarinet, a centaur dyed all the colours of the rainbow. A knife thrower in garish green strides purposefully to the right, her cloak flapping violently as her assistant with a glowing yellow face trails behind banging a drum. Chagall’s vision is a vividly-coloured, musically-charged, whirlwind band of circus performers. They are presented as if from a fever dream: removed from ordinary reality, closer in kind to the extra-ordinary – the spiritual. This richly imaginative scene reveals the close association between the circus and religion for Chagall. As he wrote: ‘I have always regarded clowns, acrobats and actors as beings of tragic humanity, to my mind they resemble the figures of certain religious paintings’ (quoted in op. cit., n.p.) Indeed, the 1950s saw Chagall engaging with religious iconography with a new vigour, no doubt encouraged by his second journey to Israel in 1951, and he devoted a major series of paintings – the Message Biblique – to Biblical themes. In both Le Cirque du Paradis and this series, begun in 1958, one sees Chagall’s skilful union of religion and pageantry, of the worldly and ethereal, in a powerful and engaging composition.

This work is accompanied by a certificate from the Comité Marc Chagall dated 2012 and numbered 2012086 A.