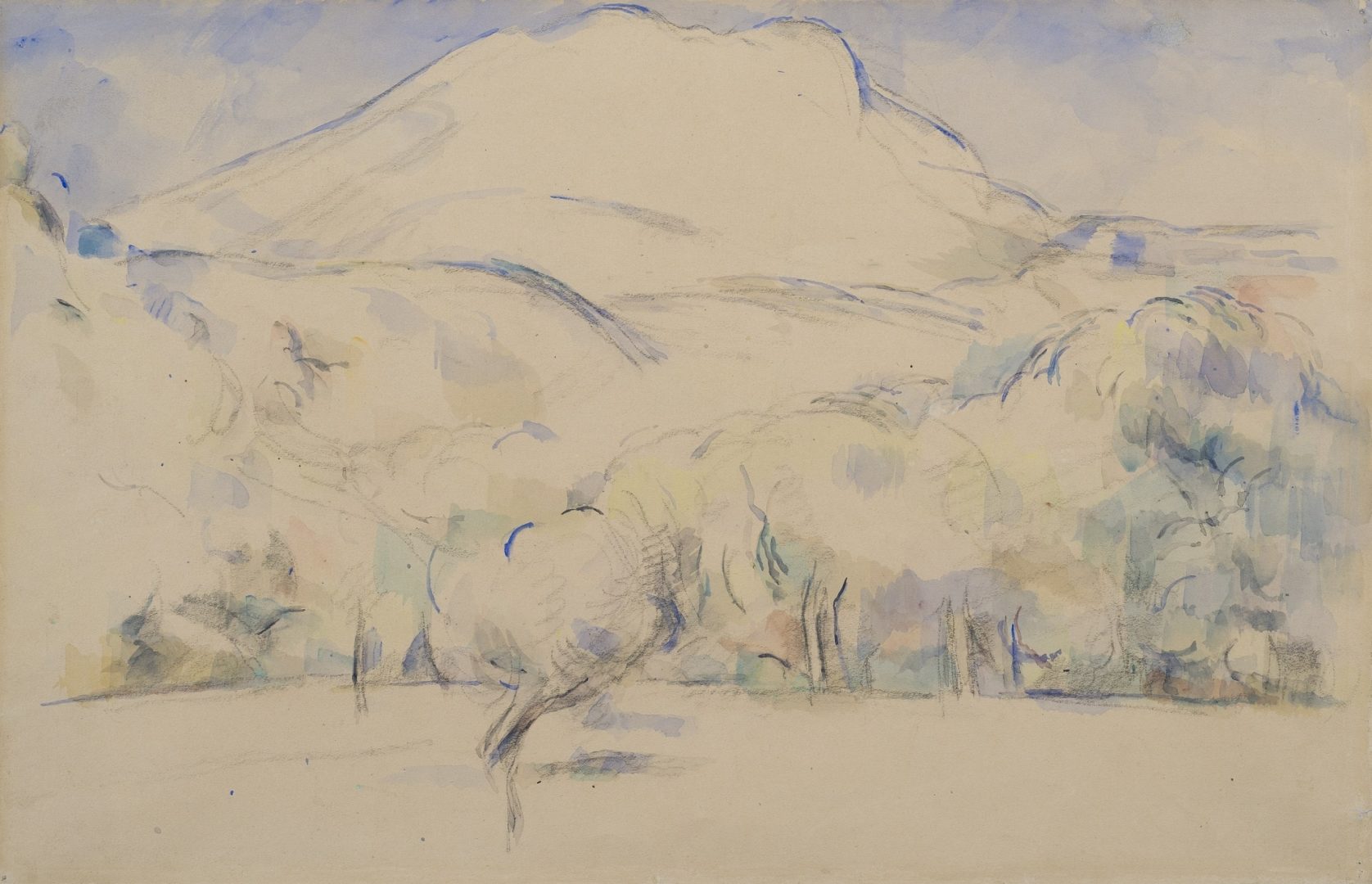

Paul Cézanne

La Montagne Sainte-Victoire, c. 1890

Provenance:

Ambroise Vollard, Paris.

Leo & Gertrude Stein, Paris, acquired from the above, by Jan. 1909.

Gertrude Stein, Paris, by 1913.

Paul Rosenberg, Paris.

Justin K. Thannhauser, Paris and Berlin.

G.Perron, Berlin.

Gustav Schweitzer, Berlin, by 1937.

Dalzell Hatfield Gallery, Los Angeles.

Norton Simon, Los Angeles.

His Sale; Sotheby’s Parke-Bernet, New York, 21 Oct. 1971, lot 74.

E.V. Thaw & Co., New York, acquired at the above sale.

Benjamin E. Bensinger, Chicago and Beverly Hills.

His Sale; Christie’s, London, 15 Apr. 1975, lot 27.

Private Collection, Switzerland.

Literature:

Vollard Archives, photo no. 151.

E. Bernard, ‘Les Aquarelles de Cézanne’, Amour de l’Art, Feb. 1924, p. 34 (illus.)

L. Venturi, Cézanne, son art, son oeuvre, Paris, 1936, no. 1563 (illus. vol. II, pl. 395).

J. Rewald, Paul Cézanne: The Watercolors, A Catalogue Raisonne, New York, 1984, p. 154, no. 288 (illus. p. 340, colour pl. 25).

D. Coutagne et al, Les Sites Cézanniens du Pays d’Aix, Paris, 1996, p. 157 (illus.)

P. Conisbee and D. Coutagne, Cézanne in Provence, exh. cat., National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2006, p. 170 (illus. pl. 61).

R. McD. Parker, ‘Catalogue of the Stein Collections’, in The Steins Collect: Matisse, Picasso, and the Parisian Avant-Garde, exh. cat., ed. J. Bishop et al, San Francisco, New York and Paris, 2011, p. 397, no. 18 (illus. in a photograph, p. 366, pl. 351; p. 368, pl. 353; p. 372, pl. 357).

Exhibited:

(Possibly) Paris, Vollard Gallery, 1895.

Paris, Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Exposition Paul Cézanne (au profit de la caisse du monument Cézanne), 3 – 22 March 1924.

Basel, Kunsthalle, Paul Cézanne, 30 Aug. – 12 Oct. 1936, no. 152.

San Francisco, Museum of Art, Paul Cézanne: Exhibition of Paintings, Water-colors, Drawings and Prints, 1 Sept. – 4 Oct. 1937, no. 47.

Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Special Exhibition for the College Art Association, 1965.

Tübingen, Kunsthalle, Paul Cézanne: Aquarelle, 16 Jan. – 21 March 1982, no. 31; this exhibition later travelled to Zurich, Kunsthaus, 2 April – 31 May 1982.

Aix-en-Provence, Musée Granet, Sainte-Victoire, Cézanne, 16 June – 2 Sept. 1990, no. 15 (illus. fig. 186).

Aix-en-Provence, Musée Granet, Cézanne in Provence, 9 June – 17 Sept. 2006, no. 61; this exhibition later travelled to Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, 29 Jan. – 7 May 2006 (but this work was not included in the Washington exhibition).

‘I try to render perspective through colour alone…I proceed very slowly, for nature reveals herself to me in complex form, and constant progress must be made. One must see one’s model correctly and experience it in the right way, and furthermore, express oneself with distinction and strength.’ (quoted in J. Rewald, Cézanne, New York, 1986, p. 159).

To the east of Aix-en-Provence, in the Sainte-Victoire Massif range, towering above the River Arc, stands the distinctive grey limestone silhouette of Mont Sainte-Victoire. The landmark remained a seminal motif for Paul Cézanne between 1877 and his death nearly three decades later, appearing in both oils and watercolours, either dominating the page or hovering on the distant horizon, and clearly identifiable by its flattened summit. In Cézanne’s watercolour La Montagne Sainte-Victoire of circa 1890, the mountain looms large, its top nearly touching the upper margin of the page. With a provenance that reads like a who’s who of Post-Impressionist dealers and collectors, La Montagne Sainte-Victoire depicts the mountain as at once both timeless and ephemeral, ‘a weightless, hovering form, suffused with light like the sky’ (T. Reff, in Cézanne: The Late Work, exh. cat., Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1977, p. 29).

At the time he painted La Montagne Sainte-Victoire, which Venturi dated slightly later than Rewald (1890 – 1900, later revising to 1895 – 1900), Cézanne was in his mid-50s. He had recently come into a sizeable inheritance following the death of his father, Louis-Auguste, in 1886. Although he now had the means to travel abroad, Cézanne preferred to remain in the vicinity of Aix-en-Provence, where until 1899 he was based at the family home, Jas de Bouffan, bought by Cézanne père in 1859. Cézanne had established a studio there in 1880, painting near the house as well as at Bellevue, to the southwest, where his sister owned a farm.

Although it can be difficult to determine the precise spot from which some of the Mont Sainte-Victoire views are taken, many of those from the 1890s were painted in the area around the Bibémus quarry and the Château Noir, roughly halfway between Aix proper and the mountain. Given the perspective of our view, which is clearly taken from a relatively proximate vantage point, with the mountain surging upward, it can certainly be included in that group. After 1899, when Jas de Bouffan was sold, Cézanne mainly painted from Les Lauves, a spot that was both to the north (so that the silhouette of the mountain appears slightly different) and more remote.

Our watercolour can be compared to, for example, a contemporary view of La Montagne Sainte-Victoire, on the reverse of which is noted that it was made near Bibémus. It might also be compared to a version Rewald dates to circa 1900. In both of these, and in others, the mountain stretches nearly to the top of the page, and is not separated from the viewer by the Poussin-esque repoussoir tree Cézanne had employed in earlier landscapes.

Cézanne’s watercolours are seldom directly associated with his oil paintings and were generally conceived as independent thoughts rather than as preparatory studies. While his early efforts are more dependent on a pencil skeleton or sketched framework, his late watercolours are constructed almost entirely in translucent wash, with the white of the paper assuming a new prominence. Beginning in the late 1870s, Cézanne adopted his signature ‘constructive stroke’, a square and diagonal brush mark that declared the supremacy of surface pattern over the perceived texture of the subject itself. Cézanne’s friend and correspondent, fellow Post-Impressionist Émile Bernard, visited Cézanne in Aix in 1904, and described his working method as ‘remarkable, absolutely different from the usual process, and extremely complicated. He began on the shadow with a single patch, which he then overlapped with a second, then a third, until all those tints, hinging one to another like screens, not only coloured the object but modelled its form’ (quoted in J. Rewald, op. cit., 1983, p. 238). Significantly, Cézanne also allowed each patch to dry fully before applying the subsequent one, so that the translucent colours appear as overlapping yet distinct planes rather than bleeding into one another as in the wet-in-wet technique. It was to Bernard that Cézanne penned his famous 1904 letter, in which he recommended Bernard ‘deal with nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere and the cone, all placed in perspective…’ (15 April 1904).

It was also around this time, circa 1890, that Cézanne moved away from his earlier repoussoir compositions, preferring instead to let the mountain stand on its own. Increasingly too, the white of the paper assumed a greater prominence, meaning that – as Rewald reminds us – the substantial areas of visible white paper do not necessarily indicate that the work is unfinished (although some of Cézanne’s watercolours are). In views such as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire, in which the titular mountain appears largely unpainted amid the pastel washes defining the sky and trees, the ‘harmony’ (to borrow Rewald’s term) that exists between the areas of white and colour is very likely deliberate.

The appeal of La Montagne Sainte-Victoire is enhanced by its impressive provenance. This watercolour view was first owned by the dealer Ambroise Vollard, who began representing Cézanne in 1895, having been urged to do so by Degas, Pissarro, and other admirers whose own reputations were more secure. The show staged at Vollard’s premises in November of that year included a number of watercolours, and helped to establish a market for them. The artist’s son, also called Paul, assisted his father in selecting works for the 1895 show, and contributed again in 1905 when Vollard staged an exhibition dedicated exclusively to Cézanne’s watercolours. Works on paper, it seemed, were easier to sell, because they represented a less substantial investment on the part of collectors in the work of a painter still considered controversial; Vollard typically paid around 200 ffr for oil paintings, and about a fifth as much for watercolours. This watercolour, executed around 1890, may have been included in the first Vollard exhibition, for which there is no extant list.

La Montagne Sainte-Victoire passed subsequently into the collection of Leo and Gertrude Stein, the great American sibling modern art collectors, who presumably purchased it from Vollard. When Leo and Gertrude had a falling-out in 1914, the watercolour remained with Gertrude, and indeed a letter penned that year from Leo to Gertrude describes the division of the art collection; he specifically notes ‘The Cézannes had to be divided’, although ultimately he left them all with Gertrude apart from a Still Life of Five Apples (Barnes Collection, Philadelphia).

From Gertrude’s collection La Montagne Sainte-Victoire passed to Paul Rosenberg, the great Parisian dealer in Impressionist and Modern art, and thence to Justin Thannhauser, a German Modernism dealer based in Berlin. In 1936, it appeared in an exhibition in Basel, where it was most likely either number 72 or 73 (Rewald records it as no. 152, but the catalogue only went up to no. 147). After a period in two other Berlin collections and dealerships, the watercolour next made its way to a Los Angeles gallery from whence it was acquired by the American industrialist collector Norton Simon, much of whose collection is housed in the eponymous museum in Pasadena. La Montagne Sainte-Victoire, however, appeared in one of the three Norton Simon sales at which Norton Simon dispersed part of his collection in the 1970s. There, it was purchased by the great works on paper collector Eugene V. Thaw for his New York dealership. Thaw, in turn, sold it to Benjamin Edward Bensinger, the Chicago and Beverly Hills-based scion of Brunswick corps and real estate mogul. His collection was offered at Christie’s in London in 1975, whereupon the Cézanne was acquired by a Swiss collector.

In October 1907, shortly after Cézanne’s death, a retrospective exhibition was staged at the Salon d’Automne. His sculptural style, with its focus on dimensionality and the depiction of volume and space, inspired the development of cubism, as artists like Braque and Picasso experimented with the fracturing of forms and the representation of multiple simultaneous viewpoints. Picasso later proclaimed Cézanne ‘the father of us all’. Another admirer, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, was particularly struck by the watercolours, declaring them ‘…very beautiful. They show as much assurance as the paintings and are as light as the others are massive. Landscapes, very slight pencil outlines upon which falls only here and there, as though to emphasize or to confirm, an accident of colour, a series of washes, admirably arranged and with great sureness of touch: like the echo of a melody.’ (R.M. Rilke to P. Modersohn-Becker, 28 June 1907, quoted in Rewald, op. cit., 1983, p. 39).