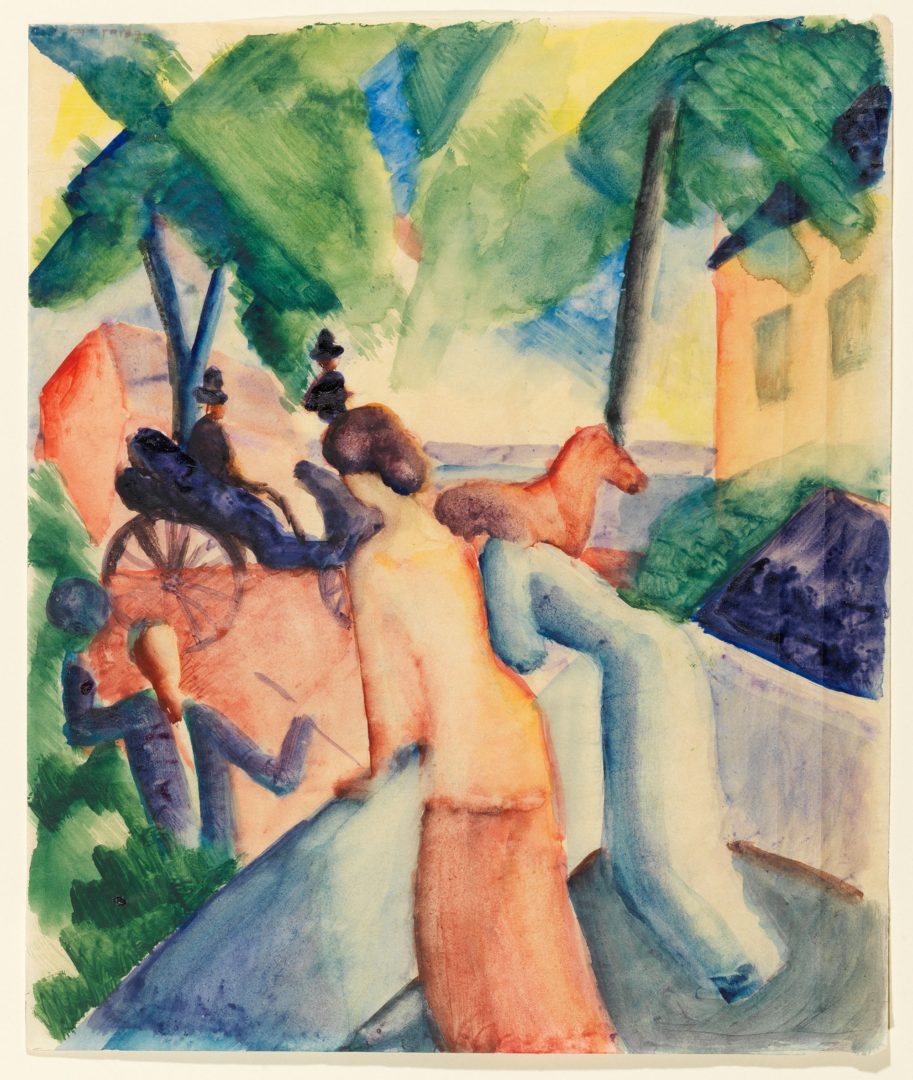

August Macke

Bergrüssung (Greeting), 1913

Provenance:

Collection Rech, Bonn.

Marianne Storp, Bonn, by descent.

Anon. Sale; Galerie Kornfeld, Bern, 20 June 1997, lot 81.

Private Collection, USA, acquired at the above sale.

Literature:

G. Vriesen, August Macke: Catalogue Raisonné, Stuttgart, 1953, no. 275 (illus. p. 287).

J.M. McCullagh, August Macke and the Vision of Paradise: An Iconographic Analysis, Ph.D., University of Texas, Austin, p. 108.

U. Heiderich, August Macke: Acquarelle. Werkverzeichnis, Berlin, 1997, no. 383, p. 310 (illus. in colour p. 114).

Exhibited:

Bielefeld, Städtisches Kunsthaus, Macke, Acquarell-Ausstellung, 23 June – 21 July 1957, no. 275.

This work reflects an array of influences that played a key role in the development of Macke’s mature style. The use of bright, radiant tones and their application in wide, spontaneous brush strokes show Macke’s debt to the Fauve painters, while the overlapping, broken planes clearly reflect Paul Klee’s influence. Macke was one of the first members of the Der Blaue Reiter group to recognise the importance of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art, and to adapt the colour theories of the French avant-garde painters to his own use. He first visited Paris in 1907, but it was not until 1909 that he saw the works of the Fauves, whose bold use of vibrant colour made a strong impression. In 1912, the twenty-five year-old Macke saw the pivotal Italian Futurist exhibition organised by Herwarth Walden at Galerie der Sturm in Berlin. The impact of this exhibition on the German avant-garde and Der Blaue Reiter in particular was phenomenal. The young Germans were confronted with paintings that were quintessentially different from the more traditionally Impressionist pictures of Max Liebermann and Lovis Corinth. Shortly afterwards, in late 1912, Macke and Franz Marc visited Robert Delaunay in Paris. Delaunay’s work was already familiar to them as were his avant-garde theories regarding pictorial composition and the new language of ‘Orphism’. From the Futurists, Macke and Marc learned the importance of dramatic light effects and the way to convey movement in two dimensions.

In this piece, Macke adapted his painting method to accommodate the subtleties of painting in watercolour, devising a feathering technique that produces an extraordinary surface and lends subtlety to the sheet. It displays Macke’s virtuosity in colour modulations, particularly in the saturated hues of red, green and blue, which are set apart by volume, tone and light qualities rather than through strict linear separations.

The composition is arranged in a steep perspective, progressing from the women in the foreground, via the man offering a greeting and horse-drawn carriage in middle ground, to the water and dramatic diagonality of the trees beyond. This scene is representative of Macke’s mature period, with people walking on a street or in a park. The work relates to a less-finished watercolour which reveals much about the construction of Bergrüssung. Unlike other Expressionists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Macke’s representations have a soft tone, and his figures appear to be at ease in their environment.

Although Macke’s paintings often focus on the depiction of male and female figures, he shows no interest in their individuality, their facial features or expressions. Whilst retaining the recognisable, figurative subject matter, he shows an increasing move towards abstraction. As he did in this watercolour, Macke relied on form and colour to communicate meaning and emotion. The composition has its own internal structure of pictorial means independent of naturalistic devices and details. Influenced by contemporary trends towards abstraction, Macke retained the traditional theme of figures in a landscape, but broke them down into basic pictorial elements of colour and form. It was in 1913 that colour became the single most important element in his painting. Macke wrote in 1913: ‘The most important thing for me is the direct observation of nature in its light-filled existence /…/ What I cherish is the observation of the movement of colours. Only in this have I found the laws of those simultaneous and complementary colour contrasts that nourish the actual rhythm of my vision. In this I find the actual essence, an essence which is not born of an a priori system or theory’ (quoted in G. Vriesen, August Macke, Suttgart, 1953, p. 120).

On the 4th August 1914 the First World War broke out and Macke was drafted into the German army. On the 26th September he fell at Perthe-les-Hurles in Champagne, leaving the works of the summer of 1914 as his last major series of paintings.