“Always read stuff which will make you look good if you die in the middle of reading it.” (P.J. O’Rourke)

What to do when museums, galleries, theatres, restaurants, shops and other sources of entertainment are all closed, and the weather is gloomy and frosty? For many of us, the answer is: read! When Dickinson team members aren’t chasing consignments from our home offices, we’re working our way through stacks of books, many of which address topics in art. In case you also find yourself short of entertainment, here are a few of our recent favourites to inspire your next book choice. Happy reading!

Molly Dorkin, Associate Director and Head of Research:

G.L. Bernini, Elephant and Obelisk, 1667, Piazza della Minerva, Rome

I was delighted to lay my hands on a copy of An Elephant in Rome: Bernini, The Pope and the making of the Eternal City (Pallas Athene, 2020) by fellow Bostonian (and PhD classmate at Magdalene College Cambridge!) Loyd Grossman. I already knew Loyd’s writing style, like his manner of presenting, to be both engaging and deeply informative. The tone of this book – its prose accompanied by nearly as many pages of photographs, historical maps, prints, paintings and other imagery, as is fitting for an art history text! – is that of a knowledgeable companion on a walk through the city. In the current world climate, when travel (and, indeed, Roman sunshine!) feels very remote, it was a most welcome substitute.

John Swarbrooke, Specialist:

Timothy Behrens, Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach and Michael Andrews at Wheeler’s Restaurant in Soho, London, 1963, photograph by John Deakin

I came to Modernists and Mavericks (Thames & Hudson, 2018) by Martin Gayford after reading the author’s excellent ‘Man with a Blue Scarf’ about his sitting for a portrait by Lucian Freud. Here he draws on 30 years of interviews to paint a captivating picture of London bohemia from the Second World War to the 1970s. Including first-hand accounts of the British art scene from such key figures as Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach, David Hockney, Bridget Riley, Frank Bowling and Howard Hodgkin, among others, there are many riches to discover in this book and much new to learn about the varied movements which emerged in the period (and some excellent accompanying illustrations). Highly recommended.

Lilly Dawson, Senior Sales Associate:

Barkley Hendricks in the Nasher Museum, 2008, photographer unknown

Duke University’s Nasher Museum presented the first career retrospective of African-American artist, Barkley L. Hendrick’s paintings in 2008, titled ‘Birth of the Cool’. The exhibition featured his bold portraits and landscapes created between 1964 and 2007. Call this show and its contributors cool, hip, spiritual (you’ll know why if you’ve read the catalogue) or whatever you like, but if you weren’t able to see this exhibition in person (or its subsequent venues at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Hendrick’s alma mater, the Santa Monica Museum of Art, and the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston) this is a must-read (republished in 2017 in memory of the artist). Curated and edited by the Nasher’s contemporary curator, Trevor Schoonmaker – with contributions by Richard Powell/Duke University, Thelma Golden/Studio Museum and Franklin Sirmans/Menil Collection – you are immediately taken in by the enthusiasm, respect, love and admiration that exists between Schoonmaker and Hendricks: they ‘get’ each other and the work. As a result the reader can’t but help fall in love too. The pictures are grounded in old master iconography and method, undeniable technique and talent, and simultaneously sprinkled with aesthetic audaciousness, allure, confidence, sexiness, playfulness, honesty, emotion, sarcasm, irreverence and undeniable beauty. His life-size portrayals of the African-American and Latino culture was challenging to the status quo, but presciently then as it does now, his work illustrates a bold and empowering sense of self and community. Hendricks is an artist, in his own words, that ‘seeks to live with and cultivate the energy, the mystery, and the muses.’ I say you have done that and more, Mr. Hendricks – thank you!

Julie Stelzer, Senior Sales Director, New York:

Cover of the book. © 2019 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Boom: Mad Money, Mega Dealers, and the Rise of Contemporary Art (Public Affairs, 2019), written by Michael Schnayerson, chronicles the ascent of today’s ‘Mega’ dealers and gives the reader an inside look on how the current art market came to fruition. Filled with interviews with top dealers as well as other art world insiders, I thought ‘Boom’ was really successful at breaking down the timeline of how things started and the evolution of where we are today. I couldn’t put ‘Boom’ down and I would recommend it to anyone who wants a bit of an insider look into the industry.

Emma Ward, Managing Director:

Monuments Man James Rorimer, with notepad, as he supervises American GIs hand-carrying paintings down the steps of the castle in Neuschwanstein, Germany in May 1945, photographer unknown

Robert Edsel’s The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History (Cornerstone, 2010) is a fascinating account of what happened to Europe’s best art and antique treasures under Nazi occupation: the brave individuals – art historians and curators, not soldiers – who tirelessly fought to trace, recover and then to preserve and return the history and culture we all can enjoy today in many museums around the world. (And the movie made after the book starred George Clooney – need I say more?!)

William O’Reilly, Senior Director, New York:

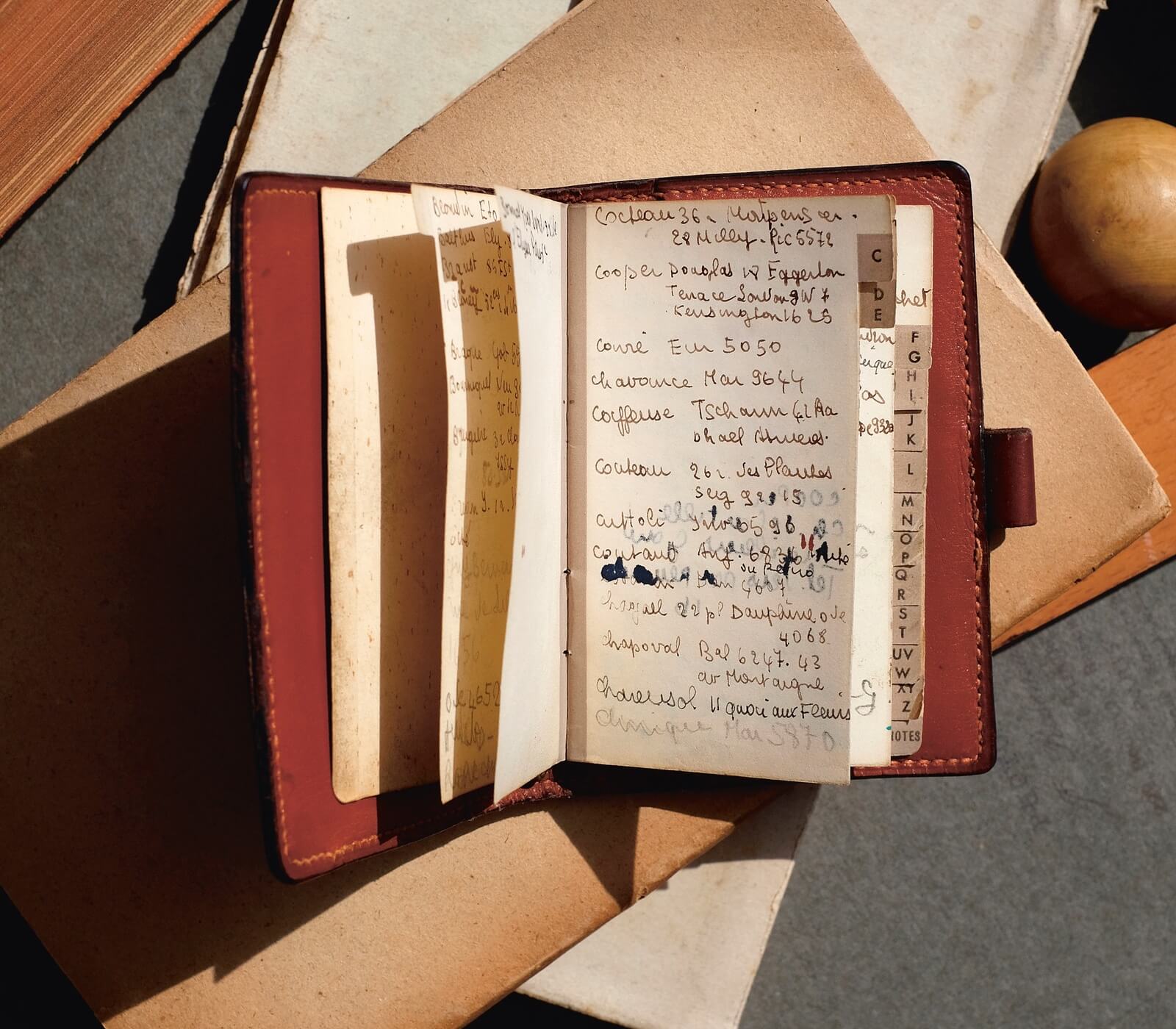

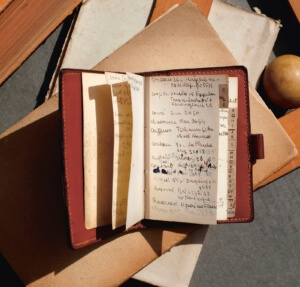

Dora Maar’s Hermès address book turned up via an eBay sale, photograph by Roxane Lagache

Some books resist classification, and by their unique perspective refresh an already well documented subject. Fittingly, I came across Brigitte Benkemoun’s Finding Dora Maar last summer, somewhere down a lockdown research rabbit hole. Benkemoun’s husband had mislaid his Hermès diary, with its time-patinated removable leather cover, and she tracked down a vintage replacement on eBay. Tucked into the back flap when the package arrived was an address book insert belonging to the previous owner, dated 1952. So begins a personal journey which takes Benkemoun across France, through Parisian archives and remote villages in the Midi. Carefully inscribed in the paper insert were the addresses and telephone numbers of almost all the luminaries of the French avant-garde, André Breton, Alberto Giacometti, Jacques Lacan, Georges Braque, Marie-Laure de Noailles and more. Intriguingly, Picasso did not feature. The handwriting was however not his, so he was ruled out, but by a process of elimination and deduction Benkemoun uncovered the identity of the former owner. Triangulating country houses and past lovers leads her to the answer. Dora Maar had been Picasso’s lover, the fabled ‘weeping woman’, in the 1930s and 40s, before being cast off in 1945. The abandonment precipitated a mental collapse and the beginning of Maar’s path towards religion and reclusiveness. The 1952 address book charts the shattered fragments of her heyday as an artist, her former life with Picasso and the artists and writers who stayed loyal. Maar was almost unique among Picasso’s consorts in having been a bold and successful artist before they met, a leading Surrealist photographer and a fixture on the Left Bank. In Finding Dora Maar, Benkemoun skillfully proceeds through the dramatis personae of Maar’s life to paint a picture of this complicated woman. Taking key figures such as Paul Eluard, Jean Cocteau and Roland Penrose, interrogating their descendants and their personal archives for echoes of the artist, she explores Maar’s own genius, the cannibalistic presence of Picasso and the febrile, fertile atmosphere of Paris before, during and after the Second World War. Along the way are gossipy sidelights on the ‘scene’, such as a description of a terrible dinner Maar endured with the Vicomtesse de Noailles and a very drunk Oscar Dominguez. A common danger working in the art world, beset on one side by the commercial pressures of the market and on the other by the ever-rolling tide of academic Art History, is to forget that every work of art is the physical expression of the social, emotional and psychological development of the artist at a specific place and time. Finding Dora Maar manages the very difficult task of providing the personal and very human context for one of the most fascinating moments of European Art.

James Roundell, Director, Impressionist & Modern Art:

Cover of the book

This is a book review with a difference! I am reviewing my own book, published back in 1974 when I was 22 years old. The subject of my book was the English 19th Century watercolourist, Thomas Shotter Boys (1803 – 1874) (Littlehampton Book Services Ltd., 1974). I had alighted on T.S. Boys’s magical watercolours of 1830s Paris while I was interning at the Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester during my vacation from Cambridge University. Being required to write a Thesis for my History of Art degree I hit upon the idea of writing about T.S. Boys, as nobody had written about him since the 1930s.

Following Cambridge I joined the Front Counter at Christie’s, hoping to be judged suitable material to join a Department. Somehow my Cambridge Thesis came to the attention of Malcolm Horsman, an avid collector of T.S. Boys watercolours. He had conceived the idea of publishing a book on the artist, and being the only person to have recently worked on him I was the natural, probably the only, choice. Horsman’s budget stretched to allowing me to visit Paris where I sought out the locations and viewpoints of Boys’s topographical images, often surprisingly unchanged 150 years on.

Next we needed a publisher who would take on such an obviously loss-making project. 1973-74 saw a global shortage of paper (in the U.S. referred to as the time of the Great Toilet Paper Shortage!) However as C.E.O. of Bowaters, the premier paper manufacturer and importer, Horsman was in prime position to negotiate supply for the publisher of his choice. A deal was struck and 2,000 copies were produced. Today copies are rarer unsigned than signed!

As I look back now on the book I still feel a sense of pride. The research was solid, and the design and production was admirable, if to our eyes in 2021 somewhat dated. One hiccup at the last moment came when Malcolm said he would like to write a Foreword. As he was paying for the whole enterprise I could hardly refuse, but I said I would like to read it through before printing. On being presented with it I quickly realised that he needed to change the first line which read, ‘I became attracted to Boys at an early age’! I am not sure I would ever have lived that down.