As seasoned collectors know, a substantial part of the value of any artwork lies in its condition. A painting may have begun its life as a portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence or a devotional panel by Jan Gossaert, but if it has been damaged or otherwise over-conserved, its value will be severely impacted. But when you request a condition report from a gallery or auction house, what does it actually mean? A reference to paint that is ‘tenting’ makes it sound like your Canaletto has gone on a camping trip, while ‘foxing’ on your Turner watercolour suggests you need to call the horses and hounds. Worry not – we’re here to help explain! Here are a few terms and expressions you’re likely to come across:

‘The panel has been cradled and this appears to be ensuring a stable structural support’

Example of a cradled panel

This has nothing to do with childcare! The wooden boards used for panel paintings are susceptible to environmental factors such as temperature and humidity, and changes – especially sudden ones – can cause the panels to warp. A cradle in conservation terms is a grid of thin, interlocking strips of wood applied to the back of a panel to hold it in place and keep it from warping. Modern cradles are designed to be more flexible than traditional ones, and can slide and shift a bit, in order to exert less force on the boards and prevent cracking.

‘This painting has a firm lining that has flattened the impasto.’

Verso of a relined artwork

Where panels can have cradles, paintings on canvas can be relined by applying a second canvas to the back of the original one (and in the past days they sometimes used aluminium!). While the intention is good – to strengthen and protect an old, and possibly very fragile, piece of material – the method itself can be surprisingly rough. Historically, conservators would apply a binder (glue or, worse, wax) to the reverse of the original canvas and then iron the new canvas onto the old one. This tended to heat, and flatten, the desirable original raised texture of oil paint, called impasto – and once impasto is flattened there is nothing you can do to return it to its original condition. Although modern conservators have more advanced techniques, including strip lining (strips of canvas! – what did you think we meant?), this explains why unlined paintings are so desirable and rare.

‘The drawing has been laid down on board.’

This is the works on paper equivalent of a canvas relining or a cradle support – paper is perhaps the most delicate of all materials and a drawing that has been ‘laid down’ has been glued or pasted to a more stable material, usually board or canvas. In this case it is often the glue or the support that can be problematic, especially if either contains acid that could damage the paper. A good conservator can advise on whether a drawing should (or indeed can) be removed from its support or is better left alone.

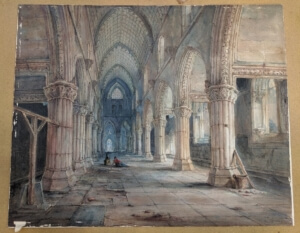

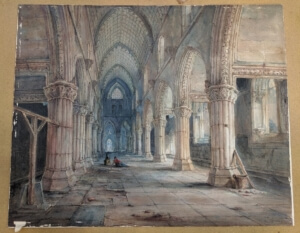

Unknown artist, Rosslyn Chapel, watercolour and gum Arabic on paper laid on board

On a related note, you can find pretty much any material laid down on other materials in an often misguided (albeit well-intentioned) attempt at preserving it: plaster frescoes can be removed from church walls and laid down on canvas; paper or canvas can be laid down on board or panel; panels can be shaved down to millimetre-thickness and laid down on canvas (this technique is called marouflage). A general rule of thumb is that the less intervention a picture has the better, especially when we’re talking about old conservation methods, but a reputable conservator can advise you further.

‘The restoration focused on the stabilisation of the tented, flaking paint layers through the consolidation and flattening of the lifting paint.’

Different stages of consolidation of tented paint

Again, moisture and humidity are to blame for this one. Over time, the binders that hold the paint to the canvas can lose their strength and the paint itself can lift away from the surface of the canvas (or panel) to form blisters that look like small tents – a dangerous development, because the next step is for the paint to flake off and be lost. A good conservator can flatten and stabilise the tented paint in order to preserve the painting’s surface. Be cautious of paintings where there is tenting that has not been addressed.

‘There is considerable foxing in the upper left-hand corner of the drawing.’

Attributed to Peter de Wint, River sketch, watercolour and pencil on paper. Small amount of foxing visible in the top left corner

While this assessment might call to mind a bucolic English country scene, it actually refers to the scattered spots of age-related browning often seen on old drawings, prints or watercolours. They’re caused by a growth of fungus or mildew relating to – you guessed it! – excessive dampness or humidity. (The term may come from the reddish-brown colour of most stains.) The good news is that foxing – unlike the other common problem seen in works on paper, fading due to light exposure – is often treatable, and a capable paper conservator can diminish or even erase the spots.

‘There is scattered retouching [or strengthening, or inpainting] to the costume of the foreground figures.’

Dickinson’s Molly Dorkin examining the condition of The Virgin and Child, by a Follower of Dieric Bouts, The Elder

These comments all point to the hand of the restorer at work, and are generally used interchangeably – although retouching or inpainting is perhaps more likely to indicate areas where the restorer has replaced missing paint, while strengthening suggests that the original paint is present albeit abraded or otherwise weakened. Sometimes these descriptions can be vague (rarely can anyone estimate that, for instance, 5% of the surface is retouching) so it is always best to look at a picture under black light, as modern retouching will fluoresce a darker colour. Except, that is, when the picture is covered by a masking varnish, which conceals – either deliberately or inadvertently – the amount of restoration in a picture. A masking varnish typically has a greenish glow under UV (ultraviolet) light.

And finally….

We should add that as Dickinson specialists we are trained to look closely at artworks but we are not trained conservators, so we make sure to call in the best in the business to prepare our condition reports – and that means specialists for works on paper, paintings, or sculpture, as needed. The conservators we work with are independent businesses so you can be sure you are getting a straightforward, non-biased opinion on each piece. And we would be pleased to meet with you to discuss any questions you may have about the condition of works in your collection, or to go through a condition report with you. Happy collecting!