“I suppose nothing brings the real air of a Tuscan town so vividly to mind as those pieces of blue and white earthenware… like fragments of the milky sky itself, fallen into the cool streets, and breaking into the darkened churches” (English critic Walter Pater, writing on the work of the Della Robbia family in 1888)

Luca della Robbia (1399/1400 – 1482), the patriarch of a Tuscan family of artists, was singled out as early as 1436 by Leon Battista Alberti in the prologue of his seminal treatise De Pictura as one of the principal protagonists of the ‘rebirth’ of Florentine art in the early quattrocento. At that time, he was practicing as a carver in stone, engaged in sculpting the marbles for the monumental cantoria of the cathedral in Florence. He made his name, however, with his rediscovery and popularisation of terracotta invetriata, applying bright, durable lead-tin glazes that fired to a distinctive shine. Luca’s closely-guarded technique – perfected and passed down to his sone Andrea (1435 – 1525), and then to his nephews Giovanni (1469 – 1529) and Girolamo – became one of the most recognisable and admired of the Florentine Renaaissance, giving rise to followers and imitators over the course of more than a century. As much an achievement in science as in art, Luca’s terracottas attracted the attention and praise of his near-contemporary Leonardo da Vinci, who saw in them a means of lending painting the permanence of sculpture.

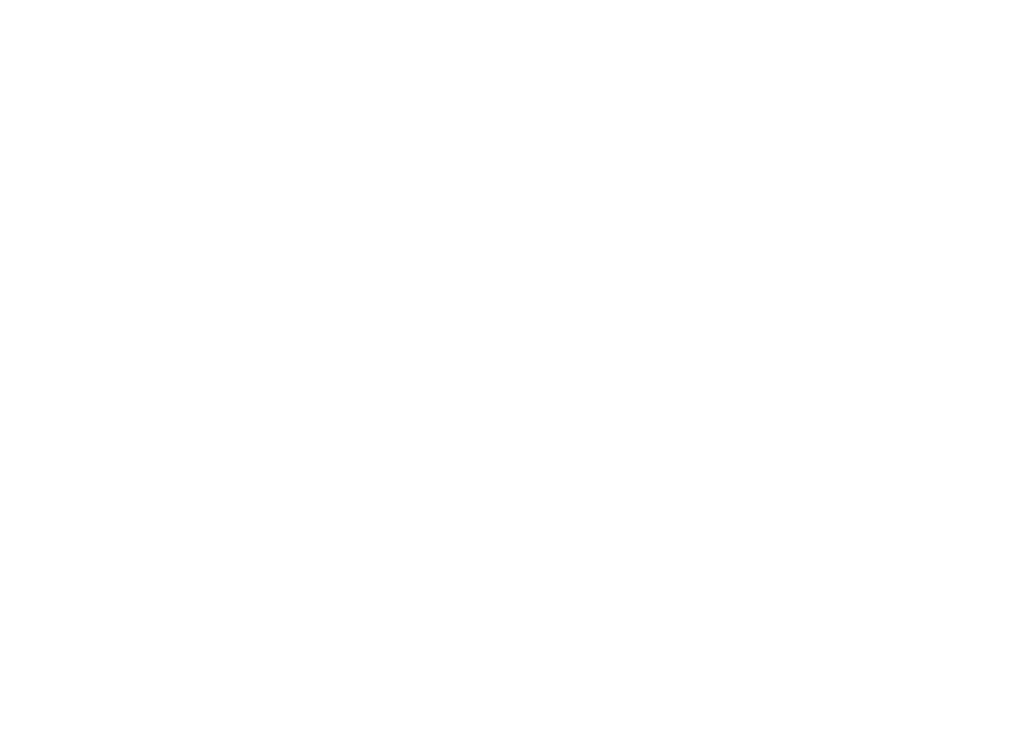

Luca della Robbia, Madonna of the Rosebush, 1450-60, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence

By 1451, Andrea is recorded as working in his father’s studio, and he took over its management following Luca’s death in 1482. Five of Andrea’s children, of whom the best known are Giovanni (1469 – 1529) and Girolamo, joined the family business, expanding the output from religious and devotional subjects to include secular ones such as portraiture, allegories and still lifes. According to Vasari, three of Giovanni’s five sons – Marco, Lucantonio and Simone – went on to join the workshop, but all three died in the mid-1520s, presumably as casualties of the plague that decimated Florence. By this time, the Della Robbia workshop had competition: Benedetto Buglioni (1461 – 1521) had probably worked as an apprentice to the Della Robbia, although, according to Vasari, ‘from a woman, who came out of the house of Andrea della Robbia, he got the secret of glazed earthenware.’ Buglioni took his knowledge to Rome, where he crafted the coat-of-arms of Pope Innocent VIII (c. 1484-92), and then passed his knowledge on to his nephew and pupil Santi Buglioni (1494 -1576).

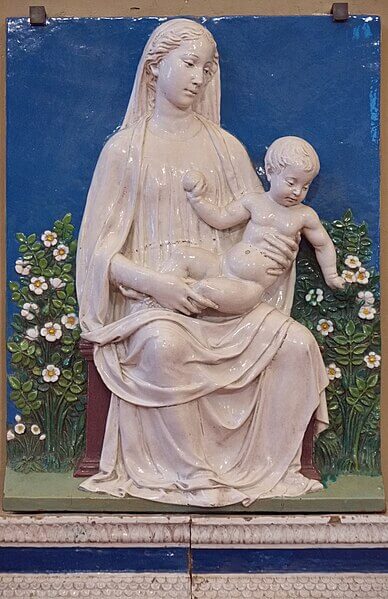

Giovanni della Robbia, Fountain from the Sacristy of Santa Maria Novella, Florence, 1498-99, Santa Maria Novella, Florence

Given the breadth and output of the Della Robbia family workshop, and the difficulty at times of attributing specific artworks to a single hand, it is interesting to consider how Della Robbia sculpture has performed on the market. The record price for any artwork by the family was achieved in 2021 for Luca della Robbia’s Relief of the Madonna and Child (c. 1450), a rare example of a securely attributed work by the master. It was deaccessioned by the Albright-Knox Gallery and sold by Sotheby’s for $2,016,500. A list of the top ten most expensive prices for pieces by the Della Robbia workshop illustrates the relative scarcity of pieces attributed to Luca and the comparable value of examples given to Andrea, Giovanni, or a family collaboration:

Luca ($2,016,500)

Andrea ($1,650,500)

Andrea ($895,500)

Andrea ($552,500)

Andrea ($485,000)

Andrea and Giovanni ($425,000)

Giovanni ($413,000)

Andrea ($377,496)

Giovanni ($350,000)

Luca ($306,497)

Luca della Robbia, Relief of the Madonna and Child, c. 1450,

sold at Sotheby’s New York, 28 January 2021

As Rachel Boyd observed in her 2020 doctoral thesis Invention, collaboration and authorship in the Renaissance workshop: The Della Robbia family and Italian glazed terracotta sculpture, c. 1430 – 1566 (Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, New York), the collaborative nature of the workshop was key to its success, and modern notions of ‘authorship’ were less important to Renaissance patrons than were the intrinsic qualities of the objects themselves. When Andrea inherited the workshop, he expanded production while remaining faithful to Luca’s original manner, relaying on deep, subtle modelling and a palette dominated by clear blue and white glazes. After his death, the workshop continued to produce impressive pieces but they rarely reached the same levels of purity or quality of modelling. Both Giovanni della Robbia and Buglione introduced a broader range of colours, which lent themselves more readily to secular subjects such as vases of seasonal fruits and flowers, but on a whole the highest prices are achieved for works considered to be by Luca or Andrea.

If we expand to look at the top 20 examples and include works by the rival Buglioni family, we can see other factors coming into play, including condition and subject:

Luca ($2,016,500)

Andrea ($1,650,500)

Andrea ($895,500)

Andrea ($552,500)

Andrea ($485,000)

Buglione ($458,500)

Andrea and Giovanni ($425,000)

Giovanni ($413,000)

Andrea ($377,496)

Giovanni ($350,000)

Luca ($306,497)

Giovanni ($281,000)

Workshop of Andrea ($227,538)

Luca ($221,911)

Giovanni ($197,702)

Giovanni ($195,552)

Giovanni ($172,645)

Giovanni ($161,150)

Attr. Buglione ($134,146)

Workshop of Giovanni ($122,500)

Benedetto Buglioni, St John the Baptist and Christ, c. 1450,

sold at Sotheby’s New York, 28 January 2021

It seems clear that, when it comes to selling artworks that originated in a collaborative working environment, now – as then – the quality of the object itself is of primary importance, but at the same time collectors recognise that Luca and Andrea were crucial to the production of the highest quality works.

Having spread from Florence to collections throughout Europe in the quattrocento and cinquecento, Renaissance enamelled terracottas can be found in major museums around the world. They were also prized among Americans travelling to Europe in the 19th and 20th Centuries, their distinctive colouring making them ideal souvenirs of Tuscany. In 2016-17, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts and the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. hosted Della Robbia: Sculpting with color in Renaissance Florence, the first exhibition dedicated to the Della Robbia to take place in the United States. Other recent shows included Émail et terre cuite à Florence: les oeuvres des Della Robbia au Musee national de la Renaissance in Écouen in 2018 and Da Brooklyn al Bargello: Giovanni della Robbia, la lunette Antinori e Stefano Arienti at the Bargello in Florence in 2017.