Claude Monet can without doubt be considered the Impressionist artist-gardener. And yet his renown as a painter often overshadows his horticultural success. For Monet himself, it was the gardens that he built at Giverny that were his greatest work of all and it is to his efforts there that we are indebted for his painterly masterpieces.

Although born in Paris, Claude Monet was a very private man and the countryside – to which he was more drawn than the city – allowed him, as it did many others, greater freedom and seclusion. As his popularity grew with the success of his career, this became all the more important. The threatening sprawl of Paris, which had been newly redesigned under the regime of the Second Empire, must have also encouraged him to take up residence in the depths of the Seine Valley. What was perhaps of most consequence to him, however, was his desire to build a comfortable home, a paradise of sorts, for his growing family.

Claude Monet, Monet’s garden at Vétheuil, 1880, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Monet’s Garden at Vétheuil (1880) is evidence of his success in this regard. The figures in this painting – Monet’s two sons and perhaps their nanny – are not immediately clear to the viewer; they are immersed in the garden, camouflaged by the haze of sunflowers swaying about their heads. The loose manner in which the artist has finished the image undeniably contributes to the boys’ relative disguise, as does the limited colour palette of blue, white and yellow, and it is helpful in giving the impression that the whole Monet family was cocooned within their father’s creation. It is clear that they revelled in the gentle pace of country life. Here, the children could explore, and Monet could continue to develop his growing passion for gardening.

Having created gardens at each of his homes throughout his life, such as that at Vétheuil, it is no surprise that Monet created the now world-famous gardens at Giverny so skilfully and these became his horticultural swansong. From the moment he arrived at Le Pressoir, his new home in the village there, Monet spent his time almost exclusively in the garden. Indeed, the first dozen years were devoted to designing and planting, rather than painting. He prioritised his obsession for gardening over his painterly profession, and Monet’s commitment to the garden in these early years speaks of his determination to create something truly beautiful, and something which he could later capture on his canvases.

In the original garden around the house, the Clos-Normand, Monet made major alterations, tearing up the kitchen garden and orchard, and articulating the space instead with wide flowerbeds and long paths. Here, Monet experimented with an ever-changing scheme, trialling endless flower and colour combinations. Even when he was away from the garden, it filled his thoughts and he is known to have sent detailed letters to his gardener, Félix Breuil, with plant lists and instructions to fill the borders to the brim.

Claude Monet, Main Path through the Garden at Giverny, 1901-02, Osterreichische Galerie, Vienna

In his painting, Main Path through the Garden at Giverny (1901-02), we can see just how successful this bountiful approach was. The painting is centred upon a pathway which divides the canvas evenly from top to bottom, and over which the bows of red spruce trees bend, shielding Monet’s house from view in a feathery haze. Beneath these trees, sporadically daubed brushstrokes in shades of red, pink, green, orange and white – each representative of a flowerhead – make up the colourful flowerbeds that dominate the lower portion of the canvas. Spilling out over the path, these borders are full to bursting and remind us of Monet’s deep love of horticulture and his determination to find a home in his garden for every one of his favourite plants.

In the Water Garden, which was developed later and is perhaps the most well-known part of the Giverny estate, Monet increasingly relaxed his horticultural approach. While the Clos-Normand had a somewhat rational layout, with regular borders and straight pathways, the Water Garden was an exercise in informality. Monet took great pains to secure the land for this new aquatic garden, which itself seems to demonstrate the depth of his passion for gardening. In its construction, which took place over many years, he made use of the River Epte, diverting its course in order to expand the size of his water-lily pond. The result was a highly naturalistic space, glade-like with its dappled shade and reflective pool.

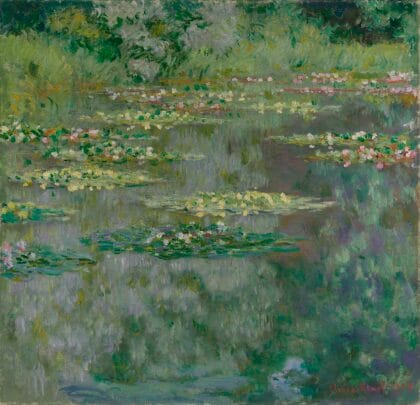

Claude Monet, The Water Lily Pond, 1904, Denver Museum of Art, Colorado

Water is very much at the centre of this garden and Monet’s paintings of it almost exclusively focus upon the pond. Indeed, he was fascinated by the play of light, particularly upon water, and one might argue that the Water Garden only came into being so that Monet could study these effects first-hand. In The Water Lily Pond (1904), for example, it is the pond rather than the planting of the garden around it that takes centre stage. It covers at least three quarters of the canvas, and even then, it is unclear where the water ends and the bank beyond begins. In fact, there is little reference to any dimension beyond the flat surface of the canvas, save perhaps for the waterlilies, and this painting is arguably an abstract piece. It is almost as though rather than attempting to capture a snapshot of the garden, Monet has instead distilled its essence, its feeling and its colour in order to provide a sensory experience of the place.

Claude Monet’s creative career perfectly typifies that of the Impressionist artist-gardener and demonstrates how the practices of gardening and painting are deeply intertwined. Just as visitors flock to view his paintings hung on gallery walls around the world, so too do they travel to Giverny to see his garden, such is its status as one of his great masterpieces.