In the world of Old Master art dealing, the question of authorship is of paramount importance. Unlike most modern and contemporary artworks (which either are, or are not, by an artist in question), the authorship of Old Master pictures is usually located somewhere on a sliding scale from autograph, through the varying levels of studio involvement, all the way down to a mere copy. As a result, attributing Old Master paintings can be a laborious process that involves scientific analysis, connoisseurship and provenance research.

Provenance research comes with its own issues. The most problematic period in art history is almost certainly 1933 – 1945, the years of the European Nazi regime. During this time, many thousands of works of art were plundered, destroyed, or forcibly purchased, often from Jewish owners. Consequently, it is imperative that when an artwork is sold today, the art market makes sure that it understands entirely the artwork’s 1933-45 provenance, so as to avoid selling a potentially stolen artwork. However, these waters are further muddied when fake pictures, painted to deceive, have been sold to the Nazi leadership.

This is exactly what Han van Meegeren did in the 20th Century’s most notorious case of art forgery.

Henricus ‘Han’ van Meegeren was born in the Netherlands in 1889 and, after an abortive education in architecture, decided to pursue his passion for painting and drawing as an artist. During his early (and legitimate) career, Van Meegeren painted portraits and made pictures to be mass produced as Christmas cards. He also painted copies of works by Dutch Old Masters such as Frans Hals, which, although technically proficient, were disregarded by critics as derivative and unoriginal. Van Meegeren’s solution to this lukewarm response was to cease copying Old Masters and to start creating them in as convincing a way as possible.

Van Meegeren devised an ingenious plan for getting his forgeries accepted. He would fake supposedly lost early works by the great Delft painter Johannes Vermeer, a genius 17th-century painter with a disappointingly small oeuvre almost entirely made up of interior genre scene of everyday life in Delft. However, in 1901 a large, boldly painted religious composition, Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, was discovered to be an early work by the artist. The picture, now in the Scottish National Gallery, shows an awareness of Italian religious painting, and led scholars to (wrongly) believe that Vermeer must have trained in Italy and that, consequently, there were many more early biblical works waiting to be discovered. Van Meegeren was more than happy to oblige them.

Johannes Vermeer, Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, c. 1655, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

Working on 17th-century canvases and using paints he mixed himself, Van Meegeren set about trying to create paintings that looked three hundred years old. One of the main characteristics of old pictures is craquelure – cracks in the picture surface that appear as the paint hardens over decades and centuries. In order to achieve this effect in freshly painted works, Van Meegeren devised a technique of mixing his pigments with phenol formaldehyde (the plastic-like substance also known as Bakelite), which, after he baked his paintings, would harden, forming cracks.

The stage was set for Van Meegeren to fool the art world. In 1937, he completed his best fake Vermeer yet, The Supper at Emmaus. To make the picture chime with art historical thinking at the time, he based his composition on Caravaggio’s treatment of the subject, leading scholars to draw the conclusion that he had studied the Italian’s work when he was living there.

Han van Meegeren, The Supper at Emmaus, 1937, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

The picture was shown to Dr Abraham Bredius, a pre-eminent scholar of Dutch Golden Age paintings, who, taken in, declared the painting to be ‘the masterpiece of Johannes Vermeer of Delft’ (quoted in The Burlington Magazine, 1937). The picture’s attribution was not only confirmed by Bredius’ supposed connoisseurship, but was supported by satisfactory testing by x-rays, pigment analysis, and inspection under a microscope. The picture was bought for 520,000 Guilders (equivalent to over €4.5 million today), and donated to the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam.

Now a wealthy man, Van Meegeren continued to produce fake early Vermeers, including a monumental Last Supper, as well as forgeries of other artists such as Pieter de Hooch. With the Second World War and its accompanying Nazi occupation came opportunity for Van Meegeren, who sold another of his creations, Christ with the Adultress, to the Nazi art dealer, Alois Miedl. Miedl, a Dutch citizen, made a career of forcibly buying (or looting) Jewish-owned artworks for sale to the occupying forces.

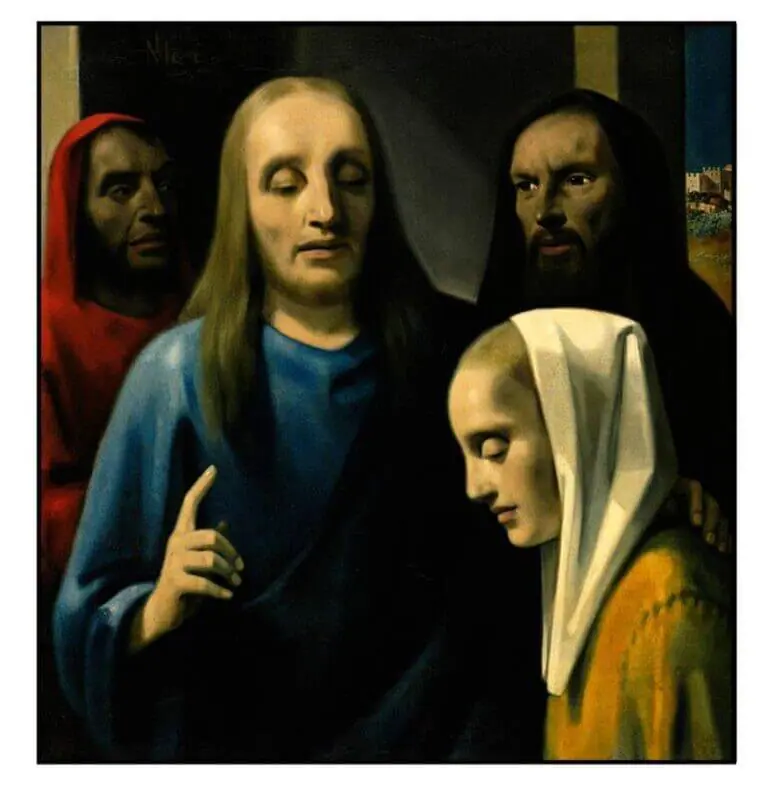

Han van Meegeren, Christ with the Adultress, 1942, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

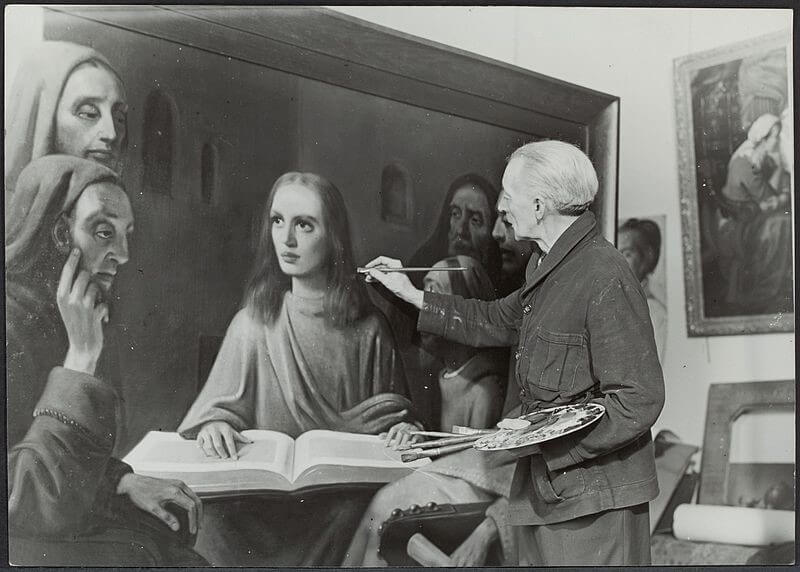

Miedl then sold the work onto the most prolific of the Nazi looters, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, who gave Miedl 137 stolen pictures in return for the supposed Vermeer masterpiece. The picture was stored in an Austrian salt mine and was recovered by the American army in 1945, after which they eventually followed the paperwork trail back to Van Meegeren. The forger was duly arrested and charged with aiding and abetting the enemy, a crime which carried the death penalty. Seeing confession as his only way out, Van Meegeren proclaimed the work to be a fake, stating ‘The picture in Göring’s hands is not, as you assume, a Vermeer of Delft, but a Van Meegeren! I painted the picture!’. Given this extraordinary revelation, Van Meegeren was ordered to paint another forgery whilst imprisoned and under the supervision of the court, to prove his claim that he was the artist. The result was his final forgery, Jesus among the Doctors. As Van Meegeren could no longer be accused of selling Dutch cultural property to the Nazis, the case was dropped.

Van Meegeren painting Jesus among the Doctors, 1945

There was one problem: by evading collaboration charges, he had proved himself a forger and thus soon found himself facing charges of fraud and forgery for the works sold before the War, many of which had ended up in state museums. This, and the discovery that he had used Bakelite, confirmed his guilt and he was sentenced to one year in prison, although he died in 1947, shortly before he was due to be imprisoned.

Amazingly, Van Meegeren’s downfall gave him not only incredible fame, but also popularity. The fact that he had knowingly committed fraud (against the Dutch state even) was apparently unimportant when compared to his reputation for fooling the despised Göring. Indeed, a 1947 poll named the forger the second most popular Dutchman, after the prime minister.

As the decades have passed (and without the immediacy of the war to cloud our judgement), Van Meegeren has inevitably become a somewhat less palatable figure. He was a known anti-Semite and there is evidence to suggest he harboured Nazi sympathies. We should be very cautious of the notion that he sold his pictures to the Nazis in a noble bid to defraud Hermann Göring. The historical record shows that he had no scruples when it came to cheating the Dutch state and we must assume he was as willing to profit from the Nazi occupation.

This extraordinary case therefore highlights the dangers of forgery in the art market. Today, it is hard to imagine any of Van Meegeren’s pictures bearing an attribution to Vermeer. Aside from the works’ obvious painterly weaknesses, museums carry out far greater due diligence when it comes to technical analysis and provenance research. Indeed, had these checks been done correctly in the 1930s and 40s, it would not have taken long to realise that Van Meegeren’s pictures had no provenance. That said, the Second World War removed the resources required for such research to take place and left the door open to people who wanted to exploit the system.

This story is also a reminder of the difficulties that arise when a picture has an uncertain mid-20th-century European provenance. Van Meegeren is a rare example of an individual who profited from Nazi intervention in the art market. In the vast majority of cases, works that passed through Nazi hands did so at the cost of others, meaning that art dealers and auction houses now have to prove that all reasonable steps are taken to avoid selling a picture that, in reality, should be restituted.