When browsing an exhibition of Impressionist paintings, it is not uncommon to spot a work with a signature that looks a bit different to what we might expect. Look more closely, and the raised edges of the text betray an interesting fact: the ‘signature’ is a stamped facsimile of the artist’s handwriting. This distinction is significant enough for galleries and auction houses to note in their catalogues when a signature is stamped rather than signed, but how does this affect the value of the artwork in question?

Signatures on artworks first began to be commonplace during the Renaissance, when the identity of the artist became more important to a work’s value, and certain artists gained a level of celebrity. (On the other hand, originality and uniqueness was less important than in the modern era, which meant that the master in an active studio might sign works painted largely by apprentices – but that is a different discussion) Artworks were signed when they were completed, which is why you would rarely find a signature on a sketch, which was considered a studio tool rather than an artwork. In the 18th and 19th Centuries, however, this began to change, and when artists died, the works – finished or otherwise – remaining in their studios is not one we see in the modern era, and they can most commonly be found on 19th and 20th Century artworks, typically Impressionist examples.

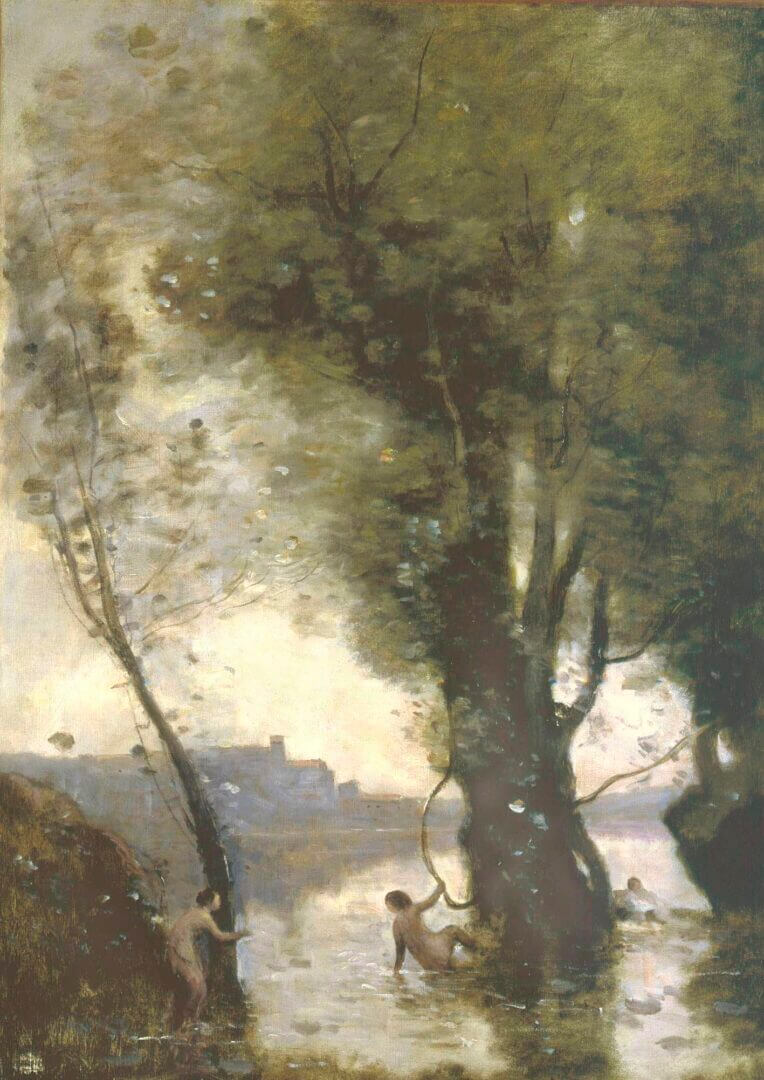

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Les Baigneuses des Îles Borromées, c. 1872, previously with Dickinson; traces of the studio stamp are visible lower left

One artist whose works frequently appear on the market with a studio stamp ‘VENTE Corot’ was Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, who died on 22 February 1875. Corot was a pivotal figure in the emergence on the plein-air landscape tradition, anticipating the work of the Impressionists with his oil sketches executed on site. This is likely the reason so many artworks remained in the artist’s studio at his death; they took three days to sell at Hôtel Drouot in Paris, from 26-28 May 1875. While, prior to the 18th century, there had been a firm demarcation between sketches made on the spot – which were considered tools rather than finished artworks worthy of conservation or display – and studio paintings, by the time the Impressionists were at work in the 19th and early 20th Century, no such distinction remained. Corot, working in the 19th Century, bridged the gap between the plein-air oil paintings – many of which were painted for the artist’s own education and enjoyment, and conserved during his lifetime – were deemed worthy of sale and stamped ‘VENTE Corot’.

Of the top 50 works by Corot sold at auction, three feature studio stamps rather than signatures. All these of these, however, are the sort of small-scale, plein-air landscape that resonates with modern taste and with collectors familiar with Impressionism.

Claude Monet, Falaises, temps gris, 1882, previously with Dickinson; signed and dated lower right Claude Monet 82

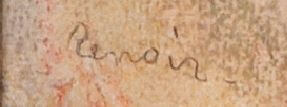

Monet’s signature

Monet signature stamp

Similarly, of the top 50 works by so-called ‘Father of Impressionism’ Claude Monet sold at auction, only five of them have stamped signatures, for 10% of the total. This seemingly suggests that collectors are more interested in works that are signed, but the story runs deeper than that. What is interesting to consider is which stamped works fetched high prices at auction: all five were waterlilies, probably the artist’s most enduringly popular subject and one that captivated him towards the end of his life. Indeed, the second most expensive work by Monet sold at auction has a stamped signature; not only is that a waterlilies scene, but it was also part of the legendary Rockefeller collection, and it would seem logical that its significant provenance also contributed to the high price it fetched.

The evidence of Monet’s paintings sold at auction would seem to indicate that, although in general collectors prefer signed works to stamped ones, with the understanding that a work signed by the artist bears his guarantee that it was completed to his satisfaction, the appearance and subject can outweigh that in importance when it comes to price, and the highest prices are fetched by an artist’s most desirable and appealing subjects and compositions. Another contributing factor is that Monet’s late waterlilies are very loose and painterly, and thus the demarcation between a ‘finished’ and ‘unfinished’ painting becomes hazier. In some cases, late, signed waterlilies can look very similar to late, stamped ones. Thus, buying a stamped Monet waterlilies does not necessarily mean buying an unfinished or unsatisfactory picture: it might be a work that is deliberately loose or that remained unsigned and in the studio when Monet died. The artist was notorious for working and reworking his paintings, and was also known to destroy unsatisfactory paintings, so there could potentially be an assumption that a stamped work remaining in his studio was satisfactory enough not to be destroyed.

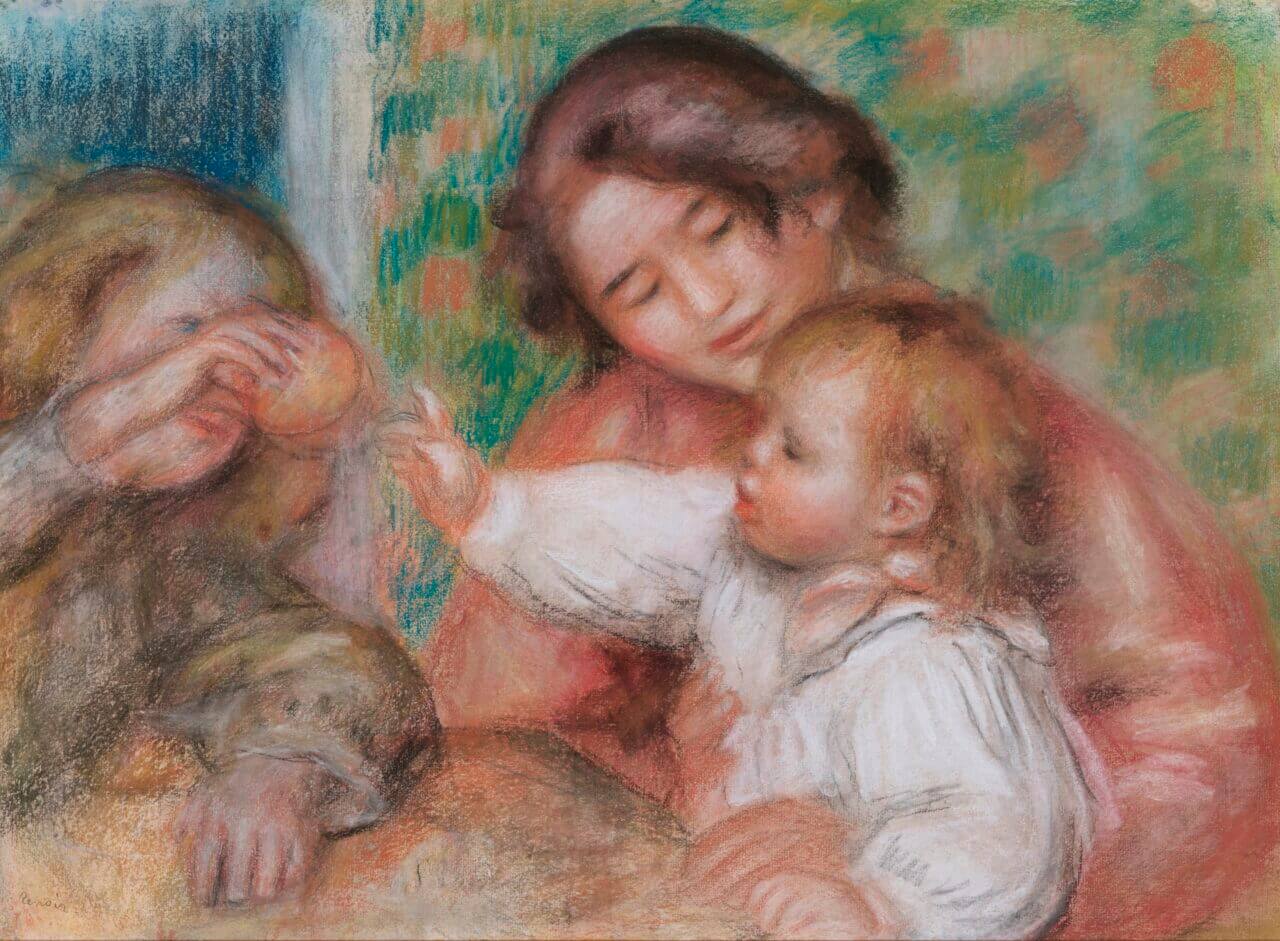

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Jean Renoir, Gabrielle et Fillette, c. 1895-96, previously with Dickinson; signed lower left Renoir

The third case study we are looking at is that of the Impressionist Pierre-Auguste Renoir, best known for his voluptuous, Rubensian nudes and luminous colouring. When Renoir died in 1919 at the age of 78, the contents of his studio were inherited by his wife Aline and the couple’s three sons, Pierre, Jean and Claude. It was presumably at their behest that unsigned paintings remaining in the artist’s studio were stamped with a signature before finding their way on the market over the years.

Interestingly, none of the top 50 works by Renoir to appear at auction bears a stamped signature. There is not even a stamped signature within the top 100 works. The highest price fetched at auction by a work with a stamped signature appears to be the $3.4m achieved by Renoir’s painting Le Déjeuner a Berneval (1898), which makes it the 111th most expensive work by the artist sold at auction. It is not immediately clear why this painting – evidently complete, dating from mid-career, and featuring the sort of domestic interior for which Renoir was justifiably celebrated – was not signed. As it depicts members of his own family, sons Pierre and Jean and Jean’s nanny Gabrielle, the artist may have chosen to keep it for sentimental reasons. It is hard to speculate on whether it would have fetched a higher price at auction had it been signed.

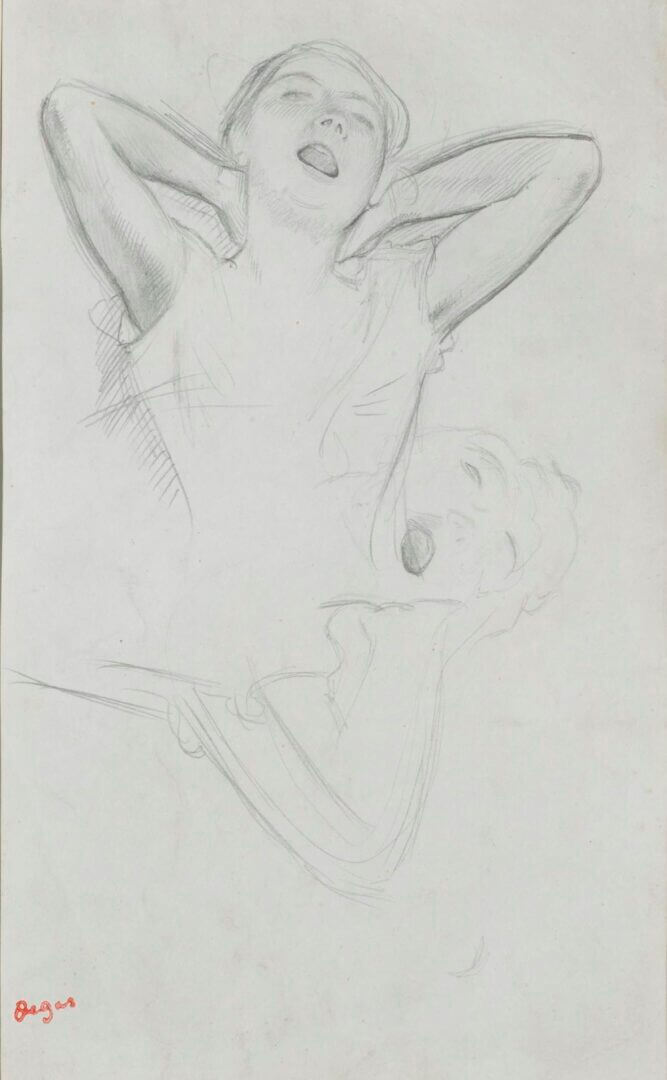

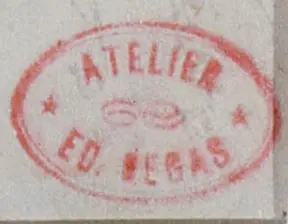

Edgar Degas, Études de Danseuse, c. 1874, previously with Dickinson; signed lower left with red Degas atelier stamp; another atelier stamp verso

Finally, we can look at the case of Edgar Degas, who died unmarried in 1917, with his estate going to family members including his younger brother René and René’s children. The Degas heirs authorised, among other things, the casting in bronze of 72 of the more than 150 pieces of sculpture that remained in Degas’ studio. (The question of posthumous casts of sculpture is a topic worthy of its own insight, to be published in future.) The Degas heirs also arranged for the red ‘Degas’ studio stamp to be applied to the paintings and works on paper left in the studio. Degas did not sign artworks until he was ready to sell them. so the lack of a signature was not necessarily an indication that a work was unfinished. It is perhaps for this reason that, among the top 50 works by Degas sold at auction, 7 are stamped rather than signed, all works on paper. Moreover, four of these dancers – the artist’s most popular subject – which tells us that, as with Monet, the subject and visual appeal remain the most important factor in establishing price.

Looking at the case studies of Corot, Monet, Renoir and Degas, it would seem that an artist’s signature, rather than a studio stamp, is desirable, and has historically impacted the price for which a work sells. A stamp does not, however, always indicate that a work is of inferior quality or unfinished. A studio stamp can signify a number of different things: that a work was left incomplete at the time of the artist’s death; that a work was never intended for sale and therefore a signature was irrelevant (either because it was considered a study or because it was a particularly personal or cherished work); or that a work was found to be unsatisfactory. What a studio stamp does tell us, of course, is that a given work can trace its provenance to the artist’s studio, which is a good sign form the point of view of authenticity.

Above all else, the qualities of the work itself – its subject, composition, and the handling of paint – remain the most important factors in determining value.