Sir Anthony van Dyck, Self Portrait, c.1640, National Portrait Gallery, London

Sir Anthony van Dyck was a painter who enjoyed tremendous success during his lifetime and who continues to appeal to collectors in the modern era. Born in comfortable circumstances and possessed of obvious talent, Van Dyck was already an independent painter in 1615, around the age of 16, and joined the Guild of St. Luke on 18 October two years later. He spent formulative years as an apprentice to Sir Peter Paul Rubens, the internationally renowned Flemish master, and six years in Italy, where he eagerly absorbed the lessons of Titian and Veronese while working for Genoese patrons. In April 1632, Van Dyck returned to London (having visited once previously, in 1621) and there he was named ‘Principalle Paynter in Ordinary’, knighted, and granted a salary of £200 per year by Charles I. He was further granted a studio in Blackfriars and a suite of rooms in Eltham Place, and catered to a noble clientele in addition to the royal family.

Even after his premature death at the age of just 42 in 1641, Van Dyck continued to exert a posthumous influence on taste and style in English portraiture – and beyond – into the 20th Century. In 1715, the artist and theorist Jonathan Richardson wrote ‘When Van Dyck came hither he brought Face-Painting to us; ever since which time… England has excel’d all the World in that great Branch of Art.’ (quoted in J. Richardson, An Essay on the theory of painting, London, 1715, p. 41). Thomas Gainsborough allegedly declared on his deathbed: ‘We are all going to heaven, and Van Dyck is of the Company.’ For the great 18th Century portraits like Gainsborough, Van Dyck continued to serve as a model, to the extent that a fashion emerged for portraits in so-called ‘Van Dyck dress’, or the style of a century earlier. This is used, most notably, in what is probably Gainsborough’s most celebrated portrait: Jonathan Buttall: The Blue Boy (1770). Gainsborough was not alone in borrowing both costume and pose from his esteemed predecessor; Allan Ramsay, Sir Joshua Reynolds, and other fashionable portraitists did the same. (For further discussion, see A. Eaker, Van Dyck and the making of English portraiture, 2022.) In the 20th Century, Van Dyck’s influence continued to exert itself on the work of society portraitists such as John Singer Sargent, about whom Auguste Rodin said in 1902 (after seeing his elegant group portrait The Misses Hunter) ‘He is the Van Dyck of our time.’

Thomas Gainsborough, Jonathan Buttall: The Blue Boy, c.1770,The Huntington Art Museum, California

John Singer Sargent, The Misses Hunter, 1902, National Gallery, London

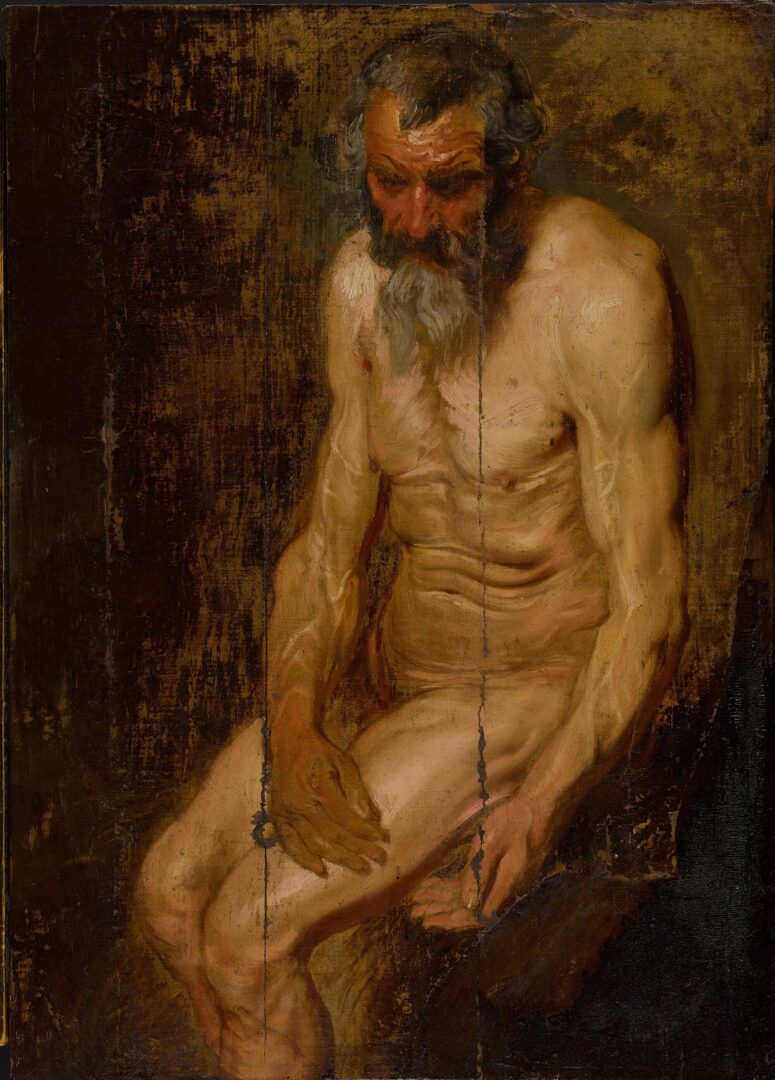

Van Dyck’s market remains robust and seemingly continues to grow. Of the top 20 prices at auction for the artist’s work, 18 were achieved within the past 2 decades, 12 within the past decade, and six within the past five years alone. The top price was set by a late Self Portrait, which fetched £8.33 million (including premium) at Sotheby’s (9 December 2009, lot 8); this was ultimately saved for the nation, and was acquired by the National Portrait Gallery five years later. The highest prices – and greatest demand among collectors – seems to be for his portraits painted towards the end of his life, particularly those featuring royal or aristocratic subjects. That is not without exception, of course; fourth on the list of top prices at auction was the $7.25 million achieved by the early Two Studies of Bearded Men (sold Sotheby’s New York, 28 January 2010, lot 176). In her article for Art Market Monitor (‘Royalty and Rediscoveries drive Van Dyck’s momentum at auction’, 12 July 2021), Angela Villa suggests that ‘the bulk of [Van Dyck’s] most expensive auction sales include museum acquisitions, rediscoveries or paintings long unseen by scholars.’ It is certainly the case that paintings by Van Dyck are regularly rediscovered and added to the artist’s canon, with recent examples of rediscoveries including:

– Study of St. Jerome, found in a farm shed in New York and sold for over $3 million at auction in January 2023

– Portrait of John VIII, Count of Nassau-Siegen, discovered in a Belgian private collection where it had descended since 1924 and sold at auction in 2020

– Saint Jerome, discovered in France in 2022 and currently for sale with Dickinson

Unlike some artists, who experienced a dip in fashion and a revival, there is no obvious period when Van Dyck fell out of favour, certainly among collectors or enthusiasts of old master portraiture. In the 19th Century, however, the sheer number of studio works and copies that proliferated and hung, under his name, on the walls of many a museum or stately home may have clouded a full and complete understanding of Van Dyck’s genius. With the 2004 publication of a new, high-colour, multi-volume catalogue raisonné, however, much of the uncertainty was clarified and the prime examples of many of his portraits and compositions identified. (Certainly not all of them, of course; Van Dyck’s reliance on studio assistance and his repetition of popular portraits – coupled with the fact that many examples are still in private hands and difficult for scholars to access and study – means that there are plenty more rediscoveries remaining to be made.)

The regularity with which international institutions stage exhibitions dedicated to Van Dyck and his circle helps to maintain his profile in public consciousness. Among the most recent are:

2019 Van Dyck (Alte Pinakothek, Munich)

2018 Van Dyck: Court Painter (Galleria Sabauda, Turin)

2017 Van Dyck: Self-portraits (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

2016 Van Dyck: the Anatomy of Portraiture (Frick Collection, New York)