Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Allegory of Winter, 1563. Kunsthisorisches Museum, Vienna.

Whilst allegorical imagery is relatively common in art, Arcimboldo’s depictions of the Four Seasons are undeniably unique. Composed of fruit and floral specimens, these “seasonal series” were first begun in 1563 and – with the exception of Autumn – the original versions of the artist’s first cycle survive to this day, including this representation of Winter. With a face and neck formed by the gnarled trunk of an old tree, the figure of Winter has a distinctly worn and weather-beaten appearance, a world apart from the abundant representations of Spring and Summer. He has a head of hair made up of tangled twigs and a mass of ivy, two fungi forming the mouth of the face, and a beard of green moss; Arcimboldo has made use of the few fruits and foliage that thrive in the depths of winter to characterise this figure. Most noticeable are the lemons hanging on a branch that grows out from the figure’s chest, perhaps a reference to the artist’s native Italy where citrus plants fruit in winter.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Hunters in the Snow, 1565. Kunsthisorisches Museum, Vienna.

In distinct contrast to Arcimboldo’s Allegory of Winter, Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s painting The Hunters in the Snow is a bountiful depiction of the winter season, one that is full of life and activity. It shows a wide, snow-covered valley or plateau peopled by animals, figures and a scattering of dwellings. To the left, three men and a pack of dogs are returning home from a successful hunt, their quarry slung on long poles over their shoulders, whilst a large group of figures gather on the frozen river down below to skate, sledge and play games. This image is very much a genre scene – a painting of everyday life – and Bruegel has carefully considered and then painstakingly rendered each and every detail of this landscape. The craggy peaks of the mountains that enclose the valley, the skeletal silhouettes of the distant trees and the glinting surfaces of the meandering waterways can all be seen with impressive clarity. The more human elements of the painting are beautifully captured too. From the swinging sign that dangles precariously above the entrance to the village inn to the figure heavily laden with a bundle of sticks determinedly crossing the bridge, the artist has created a unique sense of place and a feeling for the individual lives of its people.

Hendrick Avercamp, A Winter Scene with Skaters near a Castle, c. 1608-09. National Gallery, London.

Arguably more so than Bruegel’s painting, this Winter Scene by Hendrick Avercamp feels, thanks to its circular format, like a glimpse or view into another world. The two-pronged tree in the left foreground – beyond which we must look to enjoy the scene – and the pink castellated building, which is perfectly placed at the centre of the image, enhance the painting’s snow globe-like atmosphere. Here again, figures have congregated on the ice, seemingly dressed in their finest clothes. The two figures in the lower right foreground, skating away from the picture plane, are particularly well-dressed, and their voluminous skirt and striped hose catch our attention. Avercamp, like Bruegel, has paid great attention to detail in this painting and, despite its small scale (it measures just over 40 cm. square), we can see different acts being performed by different groups; to the left of the central tree a snowball fight is underway whilst, below the castle’s circular tower, a couple of skaters are mid-fall.

Sir Joshua Reynolds, P.R.A., Lady Caroline Scott as Winter, 1776. Private Collection.

Whilst so many anthropomorphic depictions of Winter seem to draw upon the chillier, harsher aspects of the season (such as its unforgiving weather!), Reynolds’ portrait of Lady Caroline Scott as Winter instead makes use of the sitter’s youth and hopefulness. Aged two or three, Lady Caroline Scott – daughter of the 3rd Duke of Buccleuch – is depicted here, rosy-cheeked and bright-eyed, standing by a tree before a wintry landscape. Accompanied by a faithful dog which gazes fondly up at her, Lady Caroline is dressed in a crisp white skirt and black satin cloak and appears almost as a silhouette against the frosted trees and misty skies beyond. She is, in this sense, at odds with her surroundings, and, with her hands held in a muff and a brimmed hat upon her head, she is a picture of warmth in an otherwise cold and barren landscape. Perhaps Reynolds intended Lady Caroline, with her warm, smiling face and youthful gaze, to appear as a sign of the forthcoming season of spring and the new life that it brings.

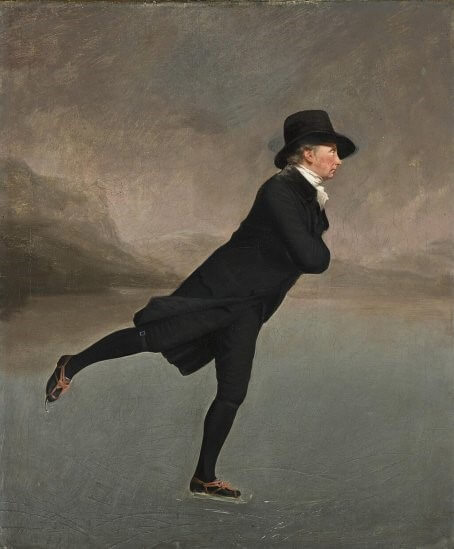

Sir Henry Raeburn, The Reverend Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch, 1790s. National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Better known as ‘The Skating Minister’, this painting by Sir Henry Raeburn of the Reverend Robert Walker is noticeably different from the artist’s other portraits. Whilst most are formal, seated depictions of aristocratic sitters, this painting shows a figure in action. A member of Edinburgh’s Skating Society (which was the first figure skating club to be formed anywhere in the world), Reverend Walker was one of a number of participants who would meet just outside of the city to skate together on Duddingston Loch. Raeburn has captured the Reverend’s movement in a way that suggests he was an accomplished skater, and the turned edge of his coat and brim of his hat appear almost blurred as though to emphasise the idea of speed. No doubt the Reverend Walker would have been a great skater, having spent some of his childhood in Holland (where his father was working at the time) and learnt to skate there. With this Dutch connection in mind, it could be said that this skating figure is reminiscent of those found in the work of earlier Dutch and Flemish artists, such as Bruegel and Avercamp; perhaps it is the icy shades of blue and grey that give such depth to the landscape, or the Reverend’s formal attire (like that of the figures in Avercamp’s A Winter Scene with Skaters near a Castle) which, to our modern eyes, hardly seems appropriate for a day on the ice!

Claude Monet, The Magpie, 1868-69. Musée d’Orsay, Paris,

Painted in Normandy during the winter of 1868-69, The Magpie is Monet’s largest and perhaps best-known winter painting. It is one of approximately 140 snow scenes that he produced in total, a testament itself to the near obsession that he and his fellow Impressionists (namely Renoir, Pissarro and Sisley) had with snow and the play of light upon it. This painting, with its low sunlight and long shadows, is a study of precisely these conditions. Here, a single magpie (which, although most likely just a compositional device, gives the painting its title) sits perched upon a gate which leads through to an idyllic landscape beyond. To the right, a clump of bare-branched trees obscures a building from view. In the middle ground, a low wall or fence topped with mounds of snow casts irregular shadows across the ground. It is undoubtedly these shadows and the contrasts between light and dark that enticed Monet to this landscape, to which his feathery brushstrokes and colour palette of subtle blues, purples, and browns with touches of yellow lend themselves so perfectly. This is a masterful depiction of a soft, snowy landscape being surveyed by a solitary bird.

Camille Pissarro, The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning, 1897. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

On 10th February 1897, Camille Pissarro took a room at the Grand Hôtel de Russie in Paris. Below, the Boulevard Montmartre – constructed only some twenty years before – bustled with bourgeois society. So inspired was he by the view from his window that Pissarro immortalised it in a series of fourteen paintings, of which this work, The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning, is one example. As a group, the Impressionists had long understood the benefits of working in series as, in focussing upon and revisiting one motif or subject, they were able to explore a variety of conditions, such as the seasons or different times of day. From the perspective of the hotel window, this painting offers a view of the Boulevard Montmartre which unfolds before us, gently curving towards the horizon. The pavements are bustling with figures, all wrapped up in hats and heavy coats, whilst carriages rattle along the main thoroughfare, slipping way into the distant mist. Much like in Monet’s The Magpie, Pissarro’s composition sees him using his daub-like brushstrokes to great effect to illustrate the crispness of a winter morning (or perhaps recently-fallen rain) in which the bustle of the city seems but a blur.

John Nash, Over The Top, 1918. John Nash, Over The Top, 1918.

Commemorating the 1st Artists’ Rifles and their active service in Northern France on the morning of 30th December 1917, John Nash’s Over The Top depicts a line of soldiers climbing out of a trench with weapons in hand, and marching off into the snow beneath a stormy sky. Their trench is like a gash in the landscape, a jagged brown tear in an otherwise pristine landscape of white snow. At the bottom of the trench, lying on the duckboards, are two fallen soldiers, casualties of the conflict in which they have been fighting. The artist’s own experience of war had an enormous impact upon his work, particularly that of the late 1910s. Indeed, two studies – both held by the Imperial War Museum – which relate to this painting, along with a number of works, suggest that Nash was, through depictions of the 1st World War, perhaps trying to come to terms with the horrors he had experience whilst fighting in France.