A fortnight of dealers’ exhibitions, auction sales and a new London art fair are over and here are some thoughts on what is happening in the market for Old Masters.

Michael Sweerts, The Artist’s Studio with a Seamstress

(Sold at Christie’s, 6 July 2023)

The market for masterpieces is growing. It is easier to sell certain works that are considered exceptional but harder to sell good quality mid-tier works. This has been a trend for at least a decade but with every passing year this trend is becoming more apparent.

The highest price at auction of last week was for a painting by Michael Sweerts. Sweerts is not a household name and therefore does not appeal to trophy hunters and yet there were at least six bidders prepared to go above the previous auction record for the artist. Estimated at £2-3 million the painting made £10.7 million (£12.6 million with the auction premium).

This painting was another discovery from a French private collection. It was, perhaps surprisingly, given a passport to leave France. Christie’s decided to sell it in London rather than Paris, a decision that might have been made to beef up their marquee London auction, but it also meant that potential bidders knew the picture was theirs for the taking; if it had been sold in Paris, the worry a museum may have pre-empted it could have dampened enthusiasm.

Why was it considered so desirable? Beautifully constructed, signed, not too large or too small, with an interesting and secular subject matter, this was a perfect auction picture. The work was dirty but seemingly in pristine condition, still unlined after 350 years. It is interesting to speculate what would have happened if it had been cleaned before the sale, which a dealer probably would have had to do if they were taking it to TEFAF Maastricht, for example. The promise is often more exciting than the reality and, conceivably, it could have made half its £12.6 million if it had been presented in ‘ready to hang’ condition.

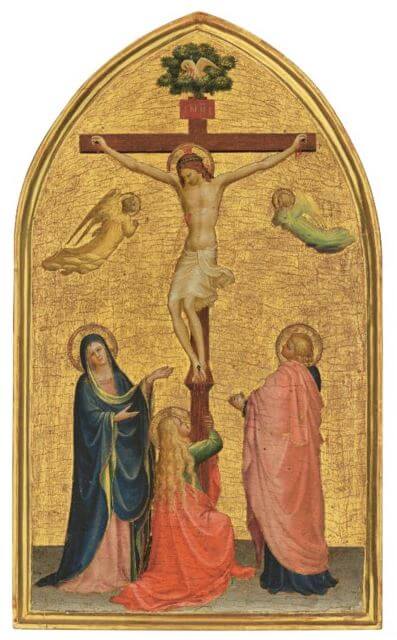

Fra Angelico, The Crucifixion with the Virgin, Saint John the Baptist and the Magdalen

(Sold at Christie’s, 6th July 2023)

This market works in strange ways and there were other artworks that may have benefitted from a different context.

Traditional works that are truly excellent examples of their kind resonate with old fashioned collectors and certain museums and would have done better to be sold privately. For example, the wonderful Fra Angelico at Christie’s had only two bids and sold for £4.2 million hammer (estimate £4-6 million) and yet in a different context its real value is probably closer to double this.

Antonio Canova, Bust of Helen

(Sold at Christie’s, 6th July 2023)

The same could be said of the marble bust of Helen by Antonio Canova. This was a faultless masterpiece in perfect condition, with an unbroken provenance from the family who had been given the bust by the artist himself. Based on comparable works, of which there are few, it was worth between £5-7 million, but estimated at £2.5-3.5 million, there were only two bidders and it sold for £2.9 million (£3.5m with auction premium). If it is exported abroad, this would be a very good opportunity for a UK institution to step in and acquire a great masterpiece with a historic connection to this country at a comparatively reasonable price.

If these works were undersold, why didn’t dealers buy them?

Understanding this is key to understanding today’s market. Even if these works were undersold, circumstances mean an art dealer couldn’t easily sell them on at a worthwhile profit. The ease of finding auction prices on the internet has changed the Old Master market beyond recognition. Before clients got a hold on Artnet, dealers would use auction as a wholesaler. When private clients could see what a dealer paid, the re-sale market became extremely difficult for dealers. Unless they can ‘add value’, by reattribution, restoration or research, Old Master dealers increasingly avoid buying at auction.

This has created an unpredictable market at auction. As dealers no longer participate as much at auction, the stabilising element they bring has been lost. Previously, if a good picture was offered with a low estimate, dealers would eye a good deal. Now, without the dealers, good pictures can sell for very little. At Sotheby’s, there was a painful run in the middle of the Evening auction where very good works by artists such as Frans van Mieris, Willem Kalf and Govert Flinck were unsold, which previously would have been bought by the trade. A lovely painting by Jacob Ruisdael made just £120,000 hammer, a price that in the past would not have been allowed to happen.

One method auction houses have used to address this unpredictability is to offer price guarantees. They guarantee the seller X amount for their painting, or persuade a third party to do so, and if there is competition above that price this is a bonus from which both sides benefit.

Sotheby’s did this extensively last week, with mixed results. They guaranteed a major private collector around £15 million for four works. For two of the pictures they guaranteed, Sotheby’s persuaded a third party to take on the guarantee instead, but approaching the sale the other two pictures were still guaranteed by Sotheby’s with their own money at risk. A pair of exquisite Canalettos, with an estimate of £3-5 million, ending up selling for £1.7 million hammer. Working on the assumption the guarantee was between £2.5-3 million, this deal would have hit Sotheby’s profits significantly. Yet, the fact that they could offer these guarantees encouraged the owner to sell through them, adding £17.7 million to their total.

The guarantee is a blessing and a curse for the auction houses. It encourages nervous sellers and reduces risk but it also affects the enjoyment of the auction itself. The gamblers see no reason to turn up and the marquee auctions become less James Bond and more KPMG.

More than ever, private collectors need to be careful and not get sucked in by hype (easier said than done).

Artemisia Gentileschi, Allegory of Sculpture

(Sold at Christie’s, 6th July 2023)

The huge growth in the market for female artists is the obvious example. Museums, particularly in America, are keenly acquiring works by female artists to address an imbalance in their collections. But they are all doing this at the same time, even though there is a shortage of decent works by female artists. A painting at Christie’s attributed to Artemisia Gentileschi, the most famous female Old Master painter, sold for an incredible £1.85 million (including premium). This painting was sold last year for €32,000 attributed to the Lombard painter Francesco Cairo. Just five years ago, Artemisia’s top price at auction was £600,000 for a major work, and now a newly attributed allegorical painting is selling for three times that.

Where does the market go from here? More of the same. At the top of the market, the competition is strong for great masterpieces and underneath that for compelling images. It is an increasingly risky auction market for sellers, where you can win big or not at all.

At Dickinson, we primarily work with private owners to help them navigate this market either as agents or advisers. There are many opportunities to buy works for good value, but the old axiom ‘buy the best you can afford’ has been proven right time and time again.

Domenico Beccafumi, The Virgin and Child with the infant St John the Baptist, St Francis and St Catherine of Siena

(Sold at Sotheby’s, 5th July 2023)