But why did so many artists have other jobs? The reasons are as varied as the examples. In the Renaissance, for instance, there was far less of a separation between fields such as architecture and engineering, or between painting in frescoes or in oils, with artists receiving a broad education through their apprenticeships. Art was very much a business, and often a family one, with sons (rarely daughters!) taking over their fathers’ workshops and artists belonging to guilds, much like other tradesmen. The concept of painting as a passion is a more modern one; thus, we regularly see 19th and 20th Century artists supporting themselves and their families by any means possible. The fortunate few – such as Caillebotte or Koons – who were or are rich enough to devote themselves full-time to art are in the minority.The old saying may be ‘don’t quit your day job’…but the art world would be considerably poorer if these and other artists had paid heed to that dictum!

Stories

Are artists lazy? Or are they the ultimate multi-taskers?

Raphael, The School of Athens, 1509-11

Renaissance

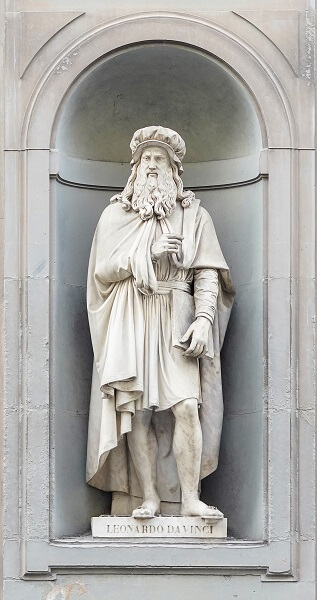

The term ‘Renaissance man’ is often used in modern parlance to describe someone with numerous talents or abilities. The original Renaissance man was surely Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519), who, in addition to his considerable talents in the creative fields of painting, draughtsmanship, sculpture and architecture, could boast achievements in diverse fields such as astronomy, botany, anatomy, cartography and engineering. Although Leonardo was unusual in the scope of his talents, it was far more common in the Renaissance for artists to work in a variety of fields; Michelangelo (1475 – 1564), for instance, was an engineer and poet as well as a painter, sculptor and architect, while Giorgio Vasari (1511 – 1574) is known primarily for his work as a historian and author of The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects although he also found success as a painter and architect himself.

Sculptural figure of Leonardo da Vinci outside the Uffizi Gallery, Florence

Other Renaissance painters were inspired in their art by a deep devotion: Fra Angelico, for instance, literally means ‘Angelic Brother’, and is the name by which Guido di Pietro (c. 1395 – 1455), a Dominican friar living in the convent of San Marco in Florence, is generally known. Having trained as an illuminator of manuscripts, Fra Angelico brought a delicacy and sensibility to the frescoes with which he decorated the monks’ cells in San Marco. Fra Filippo Lippo (c. 1406 – 1469), meanwhile, may have taken vows as a Carmelite priest, but the inspiration for his beautiful Madonnas was more earthly than heavenly: his model, a novice nun named Lucrezia Buti, became the mother of his son (and pupil) Filippino Lippi.

17th – 18th Century

It is not surprising that many artists had second careers as collectors and art dealers, among them Rembrandt (1606 – 1669) and Vermeer (1632 – 1675). Other notable artist-collectors include Royal Academy Presidents Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723 – 1792) and Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769 – 1830), with Lawrence’s collector’s stamp appearing on works from his superb collection of Old Master drawings. The successful 18th century painters in watercolour and gouache, brothers Paul (1731 – 1809) and Thomas Sandby (1721 – 1798), began their careers as military draughtsmen and surveyors, which, when you appreciate the precision and detail of their landscape watercolours, makes a great deal of sense.

Paul Sandby, Warwick Castle from the South East, 1775

Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Period

Although finding ‘Renaissance men’ among the old masters may not be particularly surprising, several artists from the Impressionist and Modern period had careers that may surprise some. The Impressionist Gustave Caillebotte (1848 – 1894) inherited a fortune from the family’s textile business, and thus was spared the need to work for an income or sell his art. Even so, he earned his law degree and worked as an engineer, before turning to painting after a period of military service during the Franco-Prussian war. Caillebotte was also a collector, whose patronage of his fellow Impressionists helped many of them out of financial straits.

Gustave Caillebotte, The Park on the Caillebotte Property at Yerres, 1875

Dutch Post-Impressionist Vincent Van Gogh (1853 – 1890) followed his older brother Theo into the commercial art world, with a period of time spent employed by Goupil & Cie, and then as a Protestant missionary, before devoting himself to his art (supported financially by Theo) at age 28. He painted seriously for just under a decade before his untimely death. Van Gogh’s close friend Paul Gauguin (1848 – 1903) was a successful Parisian stockbroker who quit that career following the 1882 market crash to pursue painting full time. Paul Cézanne (1839 – 1906) studied law at the insistence of his father, who wished him to join the family bank Cézanne & Cabassol, but he hated it and eventually abandoned the field for art. And Henri Rousseau (1844 – 1910) earned his nickname ‘Le Douanier’ (the customs officer) from his role as a tax collector; he only began painting seriously in his 40s, retiring age 49 to paint full-time.

The Modern era

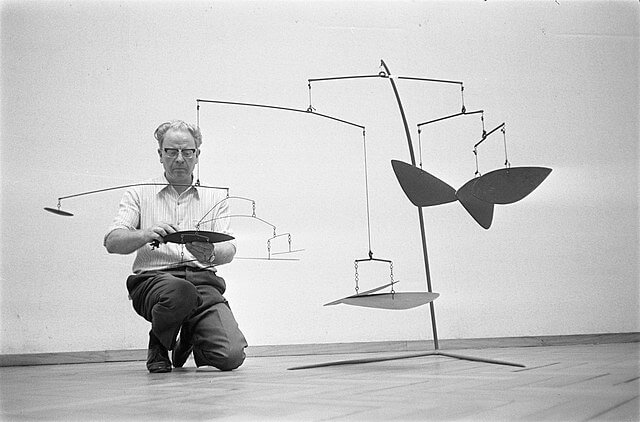

There are numerous 20th and 21st century examples of artists who became successful either later in life or after their deaths, who supported themselves with other careers. Andy Warhol’s (1928 – 1987) work as a graphic designer and illustrator, for example, led him to develop his signature form of Pop Art and screen-printing. Alexander Calder’s (1889 – 1976) work as an engineer undoubtedly taught him the skills needed to balance his kinetic sculptures with such precision. And Richard Serra’s (b. 1938) employment at a steel mill may have contributed to the development of his large-scale metal sculptures and installations. (Serra also evidently worked as a removals man…so it is perhaps ironic how difficult his signature artworks are to transport.) Jeff Koons’ (b. 1995) early success as a Wall Street commodities broker afforded him the freedom to pursue his art in the 1980s.

Alexander Calder adjusting one of his mobiles, 1969

Conclusion