Scholars and dealers throw around terms and abbreviations such as UV, infra, dendro and IR, but what do they really mean? Today we bring you a simple guide to the complex field of technical analysis, in an effort to understand what these tests can tell us – and also what their limitations are.

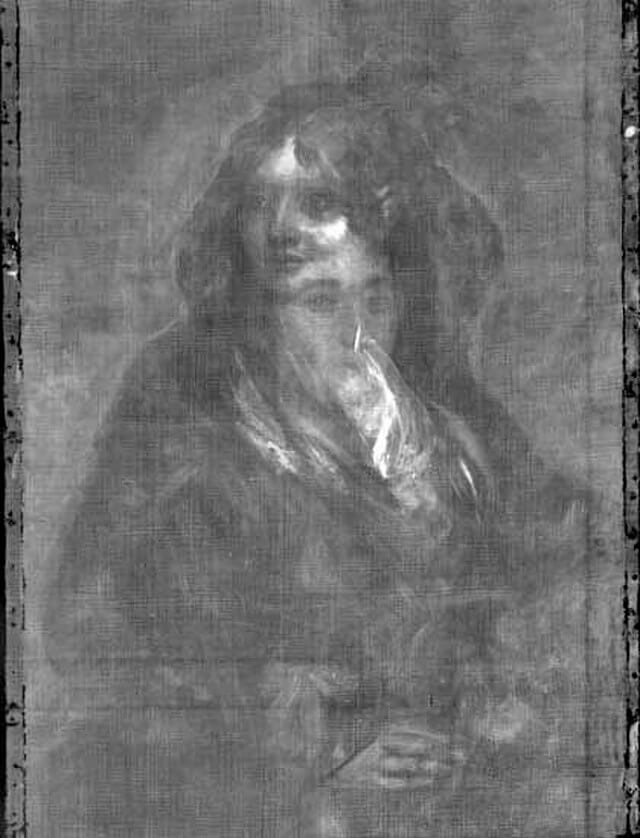

X-ray:

An x-ray of a painting uses film, just like an x-ray of teeth or bones. During the process, a sheet of radiographic film is placed against the paint layer and light is directed from beneath the painting towards the film to capture an image. X-rays can pass through many materials but they are blocked by substances made up of atoms that are especially heavy – which is why the nails used to attach a canvas to stretcher bars will show up on the film. Works on paper can be x-rayed, as can paintings on canvas and panel.

X-rays can be useful in seeing the changes that have been made to a painting over the course of its lifetime. If an image has been painted over something else – for instance, if an artist has re-purposed a canvas – then both images will appear, superimposed, in the x-ray. Areas of damage will show as dark patches, so x-rays can also be helpful in determining the condition of a work.

Ultraviolet light:

You may have seen scholars, curators or dealers shining violet-hued torches onto artworks. These are UV torches, which serve a purpose similar to an x-ray in revealing hidden information about condition. Natural resin varnish layers show up a greenish hue, so if something appears dark on top of the varnish layer, it could be a retouching or strengthening added later. If an artist’s signature fluoresces dark, then it may be a later addition by someone other than the artist him- or herself. Other dark areas may indicate that a restorer has repaired areas of abrasion, craquelure, or other damage to improve the appearance of an artwork to the naked eye. A painting may initially appear to be in excellent state until UV light reveals extensive areas of repainting to address old tears or other damage.

Infrared reflectography:

Infrared radiation shines through layers of paint until it reaches something that absorbs it, such as the carbon used in charcoal for drawing. Thus, if an artist has begun a composition by drawing a design on a canvas or panel, Infrared will reveal this. For these reasons, infrared reflectography can help in determining whether a painting is the prime (first) version of a particular composition, or a copy or version by the artist or his or her studio. The prime version will often feature changes in the underdrawing as the artist works out the composition and makes adjustments. Later versions will not typically feature such changes, as the composition has already been established to the artist’s satisfaction. Of course, there are some artists – such as Sir Joshua Reynolds – who preferred to sketch painted compositions with thinned paint rather than in charcoal, and in these cases, infrared will not be useful.

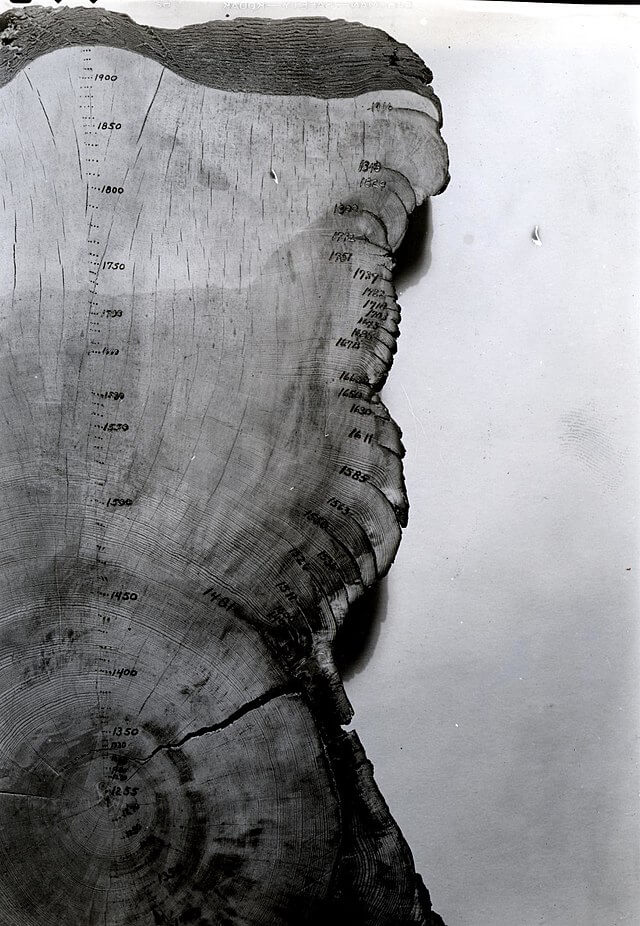

Dendrochronology:

This test (from ‘dendro’, meaning relating to trees, and ‘chronos’, or measured time) helps to establish the age of a wood panel by analysing the distances between the growth rings of the tree from which it was made. As a tree grows, its rings will thicken, and thus the grain of an oak panel can be compared to panels from different regions and dates to give an approximate age for a panel. This test is less useful for poplar, the support most commonly used in Italian panel painting, because the growing patterns of poplar are more erratic. Dendrochronology can be a helpful tool in ruling out or disproving attributions: for instance, if the test reveals that a panel was created around 1600, then the painting in question could not be by Holbein, who died in 1543.

Pigment analysis:

In this exam, scientists will take a tiny sample of pigment from a painting to analyse its materials, both organic and inorganic. This does not damage the painting itself, as the samples are so tiny. As with dendrochronology, pigment analysis can help to disprove an attribution if the pigments used post-date an artist’s lifetime. For example, if we analyse the blue pigments in a painting by Canaletto, we would expect to find Prussian blue, the first ‘modern’ synthetic pigment – which was discovered at the beginning of the 18th century. If, however, pigment analysis revealed the presence of Prussian blue in a painting attributed to Titian, who died in 1576, that would raise a red flag.

Scientific tests are yet another tool in the arsenal of the scholar seeking to make or confirm attributions, or to better understand an artist’s technique. They are not a replacement for other forms of scholarship such as archival research or visual analysis, but should be used alongside other methods in order to establish the most convincing and well-rounded opinion of an artwork and its origins.