CORONATION PORTRAITS

With the coronation of Their Majesties King Charles III and Queen Camilla fast approaching, we thought it high time to look back at some of the most (and perhaps lesser) celebrated portraits of British monarchs, right through the ages.

Queen Elizabeth I (1553 – 1603), c. 1660 – Unknown English artist

Painted by an unknown artist, this portrait is thought to be a copy of an original work dating from around 1559, now sadly lost. The composition of this painting, however, contains all the elements of a formal coronation portrait. Queen Elizabeth I is depicted here wearing an ornate gown, decorated with Tudor roses and fleur-de-lis and made of cloth of gold which, it is recorded, was first worn by Mary I and later worn by Elizabeth on the day of her own coronation in January 1559. In her right hand, she holds the Sovereign’s Sceptre – a symbol of temporal or worldly power – and in her left, the Sovereign’s Orb, a symbol of Godly power. The latter is a reminder of the Monarch’s role as God’s representative on earth and, with her palm placed firmly over it, we are aware of the determination Elizabeth had to bring order to her kingdom and people, after so many years of religious instability.

Charles II (1630 – 1685), c. 1671-76 – John Michael Wright

Equally ostentatious, if not more so, is this portrait of King Charles II by John Michael Wright. Whilst we do not know the occasion for which this work was commissioned, there are striking similarities between it and the coronation portrait of Elizabeth I. The pose of the sitter, the intricate costume details and even the symmetry of Charles II’s portrait seem to recall the earlier work, perhaps deliberately, so as to suggest an unbroken royal line and to confirm the success of the Restoration. Much like Elizabeth, Charles holds an Orb and Sceptre, which had been newly made for his coronation in April 1661 (the previous pair were melted down during the Interregnum). This same Orb and Sceptre has been used at every coronation since that date, with the Cullinan I – the world’s largest diamond – being set into the Sceptre in 1910. Seated beneath a canopy of state and dressed in vibrant red Parliament robes which cascade over his throne, Charles II appears every inch the Merry Monarch.

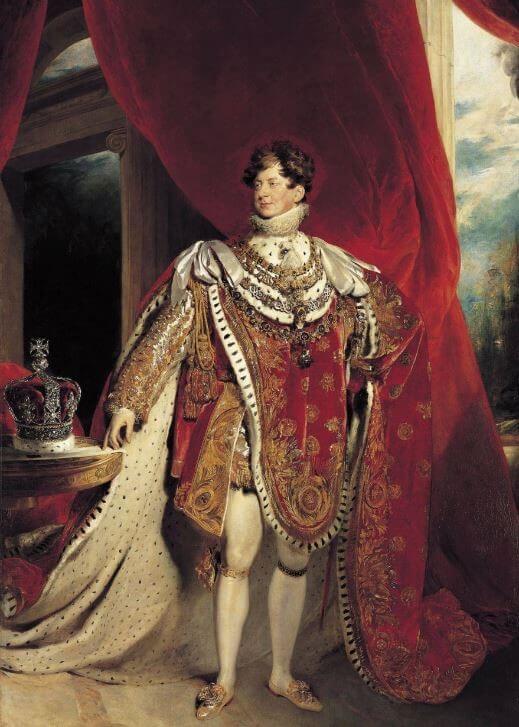

George IV (1762 – 1830), 1821 – Sir Thomas Lawrence

Sir Thomas Lawrence was “the most fashionable and also the greatest portraitist of his generation” [Royal Collection Trust]. It is of little surprise, therefore, that he succeeded Sir Joshua Reynolds as Principal Painter to George III and less surprising still that his flashy, painterly style appealed to the frivolous then-heir apparent, George IV. Commissioned as the official coronation portrait in 1821, this painting was designed for the throne room at St James’s Palace, where it hangs to this day. It remains an important visual record of the extravagant robes worn – and designed – by the King, the silhouette of which is not unlike that of the Garter robes. This detail lent itself to Lawrence who, despite the significance of the commission, created this work by painting over another portrait of George IV as Prince Regent in full Garter regalia from 1818. Consequently, he was able to follow the same outline of the Garter costume, elements of which still show through.

Queen Victoria (1819 – 1901), c.1838-40 – Sir George Hayter

Just like Lawrence, the painter of this portrait – Sir George Hayter – also held the position of Principal Painter. Whilst Queen Victoria grew to prefer the work of other artists in later life, such as that of Sir Edwin Landseer, Hayter had been instrumental in her artistic education, having helped the then-Princess with her first attempts at oil painting. This portrait depicts the Queen, dressed as she was on the day of her coronation in June 1838. She wears Coronation robes and the Imperial State Crown, the jewels for which were hired for the occasion before being returned to the Jewel House in the Tower of London. Hayter’s painting originally set Victoria within Westminster Abbey, although this was something that he later changed. In doing so, Hayter has made Victoria the sole focus of the image and, with such theatrical lighting, he has seemingly captured the innocence and vulnerability of this 19-year-old queen.

King George VI (1895 – 1952), 1938-45 – Sir Gerald Festus Kelly

Almost exactly 100 years after Queen Victoria’s commission, King George VI engaged the artist Sir Gerald Festus Kelly to paint his likeness in this portrait, along with another of his wife, Queen Elizabeth. Beginning in 1938, Kelly’s progress on the two paintings was interrupted by the outbreak of the Second World War and consequently, they were moved from his studio to Windsor Castle where he was able to continue working on them in safety. In this portrait, the King wears the star and garter of the Order of the Garter over Coronation robes and stands proudly with one hand on his hip, while the other hand supports the Sceptre (with its recent addition of the Cullinan diamond). In both this work and its pair – depicting Queen Elizabeth – the figures are stood in an interior based on the Viceroy’s House in Delhi. Having dismissed Windsor Castle’s Crimson Drawing Room as a suitable background, Kelly had his friend, Sir Edwin Lutyens, make a model of the Viceroy’s House on which he based the architectural setting of these paintings. Kelly’s choice seems fitting when we consider that George VI was the last Emperor of India, which became independent in 1947.

Queen Elizabeth II (1926 – 2022), 1953 – Sir Cecil Beaton

Praised for bringing the monarchy into the modern age, it is perhaps appropriate that the coronation portrait of Queen Elizabeth II is not a painted image, but a photographic one. Taken by the leading society photographer of the 20th century, Cecil Beaton, this portrait perfectly captures the history, magic and mystery of the British Royal Family through a thoroughly modern medium. With Elizabeth seated in profile, Beaton’s image simultaneously recalls the traditional portraits of the early Tudors – who were depicted in three-quarter view – whilst making use of the Queen’s unmistakable silhouette, as would be found on coins and postage stamps. The backdrop of Westminster Abbey too not only adheres to Beaton’s inherently theatrical aesthetic – he had taken a similar photograph of the Queen Mother in front of an image of Windsor Castle earlier that same year – but also reminds us of Sir George Hayter’s original setting for Queen Victoria’s portrait, inextricably linking these two young female leaders. Perhaps most importantly, however, Cecil Beaton has, as a person relatively intimate with the Royal Family, captured the Queen’s softness and humanity for which she is so well-remembered today.