Your move! Thanks to COVID restrictions and lockdowns, sales of board games have soared, with John Lewis reporting a 52% rise in 2020. Meanwhile, Netflix reported that The Queen’s Gambit, a scripted series about a young female chess prodigy, set a new record, with 62 million members tuning in during the show’s first month. For those of you who have found yourselves pulling out an old chess set, or perhaps dealing a hand of poker in your support bubble, we bring you some of the best paintings on the topic of gambling and games.

S. Anguissola, The Chess Game, c. 1555, National Museum, Poznań, Poland

The earliest known Western artworks depicting chess are Medieval illuminated manuscripts such as the Libro de los juegos (1283). After chess became more popular in Europe, in the 15th and 16th centuries, references began to appear more regularly in poetry, literature – and art. Sofonisba Anguissola’s The Chess Game depicts three of the artist’s sisters, two of them engaged in a game of chess and third, younger girl looking on. The work is partly allegorical in nature, with the sturdy oak in the background alluding to familial ties. Chess was considered an intellectual exercise, and thus, unlike gambling, acceptable for women. Sofonisba – who studied with Michelangelo in Rome, and served as painter to the Spanish Court – subtly underscores the achievements of her sisters by associating them with the queen, who can be defeated and recreated from a pawn.

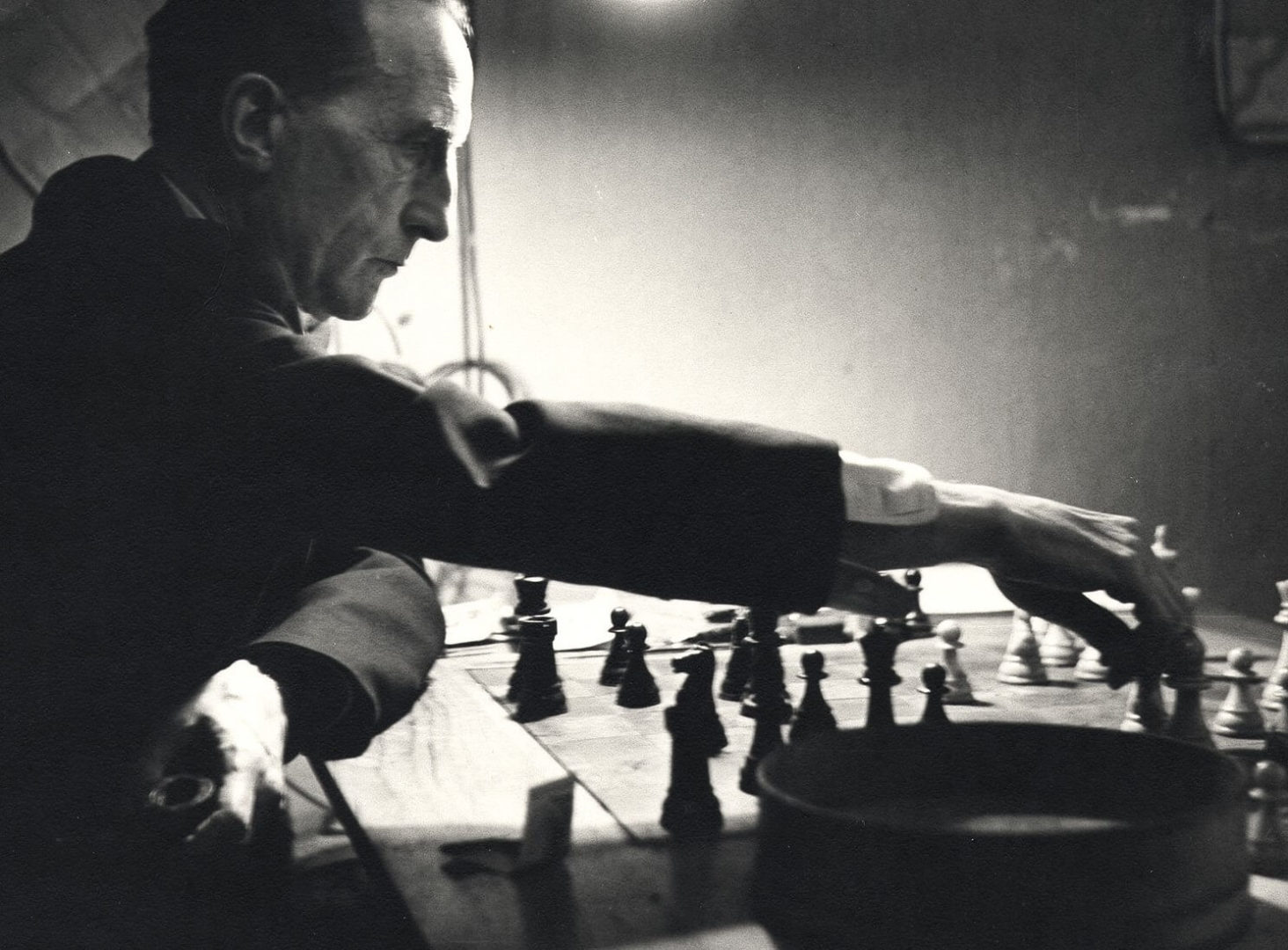

J. Lavery, The Chess Players, 1929, Tate Gallery, London

Female chess players also feature in Sir John Lavery’s 1929 painting The Chess Players, which depicts Margaret and Rosemary Scott-Ellis, daughters of Howard, 8th Baron de Walden. The sisters sit on the floor, on opposite sides of the centrally-positioned board, simultaneously relaxed and attentive.

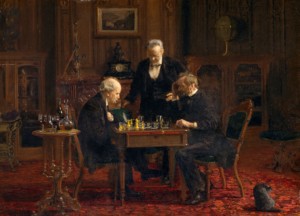

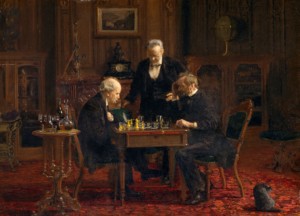

T. Eakins, The Chess Players, 1876, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In Thomas Eakins’ The Chess Players, however, the arrangement is far more formal, and shows Eakins’ own father Benjamin observing a game between French teacher Bertrand Gardel and painter George Holmes. Where Lavery’s subjects sprawl in an attitude of repose, Eakins’ players furrow their brows in concentration, not even tempted by the bottle of wine or decanter of brandy on the nearby table.

J. Steen, The Card Players in an Interior, c. 1660, Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo Collection, MFA Boston, MA

Far more susceptible to the temptations of drink – and other vices – are the gamblers in paintings by the old masters, for whom cardplaying was shorthand for all sorts of immoral behaviour. Jan Steen’s The Card Players in an Interior shows an elegantly dressed young man playing cards with a woman who, with a knowing glance at the observer, shows us a hand full of aces. The suggestion is that the scene takes place in a professional establishment; the other two men looking over the young man’s shoulder, and proffering a glass of wine, are presumably assisting in the swindle. The parallels between cheating at cards and cheating in love are clearly drawn.

M. Merisi da Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, c. 1594, Kimbell Museum, Fort Worth, TX

Caravaggio’s early work The Cardsharps also depicts an expensively dressed, but presumably unworldly and gullible, young man playing a hand of cards against an opponent, who – we can see – has several cards tucked into the waistband of his trousers. The cardsharp’s accomplice, peering over the young man’s shoulder, signals to indicate what hand he holds. The handle of a dagger, also tucked into the cardsharp’s belt, hints at the potential danger to come.

W. Hogarth, The Gaming House (part of A Rake’s Progress), 1732-33, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

Satirist William Hogarth addressed the theme of gambling in the sixth painting of his series A Rake’s Progress, which narrates the downfall of the protagonist Tom Rakewell. Tom, seen kneeling and shaking his fist in the foreground, is raging at his ill luck and the loss of his fortune at the gaming table. All around him, gamblers reveal a gamut of emotions: from jubilation to desperation, with various figures rolling dice, striking deals, and fleeing at the sudden appearance of the police. This is gambling at its least glamorous and most disreputable.

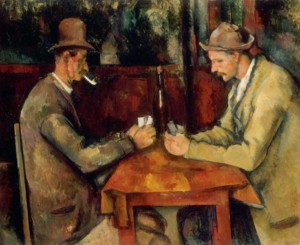

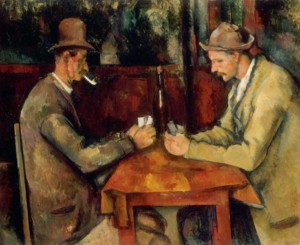

P. Cézanne, The Card Players, 1894-95, Museé d’Orsay, Paris

Paul Cézanne’s series The Card Players (early 1890s) includes five works, one of which is currently the third most expensive artwork ever sold, with a price of over $250 million achieved a decade ago. Although the paintings depict Provençal peasants at a café table, Cézanne borrowed the motif from the 17th century Dutch and Flemish genre paintings by artists such as Steen. He would also have been aware of the painting of cardplayers by the Le Nain brothers in the museum in Aix-en-Provence. Where Cézanne’s paintings differ from their 17th century predecessors is in their quiet lack of drama: while Steen’s peasants and brothel patrons sneer, leer and brawl, Cézanne’s rustic locals possess a quiet dignity that has more in common with Eakins’ chess playing pair. And where Steen’s young prostitute casts the viewer a knowing glance, making us accomplices to her ruse, Cézanne’s cardplayers maintain a quiet focus on their own game.

J. Gris, Chessboard, Glass and Dish, 1917, Philadelphia Museum of Art, PA

Cézanne was, of course, instrumental in paving the way for the emergence of Cubism at the beginning of the 20th century. When Picasso and his friend and rival Georges Braque began experimenting with the flattening of forms and the depiction of three-dimensional objects as faceted planes, they moved from Analytic Cubism to the so-called Synthetic style, which often incorporated elements of collage into the compositions. Playing cards feature in still lifes such as Picasso’s 1914 Bottle of Bass and Glass (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), not as a symbol of vice but as a collection of the sort of objects and evidence found on a Parisian café table. As in other compositions, Picasso enjoys playing with the viewer’s perception: the ‘BAS’ inscribed on the bottle represents bass ale, but the ‘AS’, standing above the playing card, is also the French word for ‘ace’. Meanwhile, Juan Gris was fascinated by the geometry of the chess board, and depicted it on several occasions in works such as Chessboard, Glass and Dish.

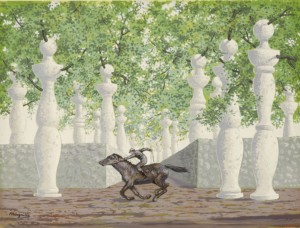

R. Magritte, Le Jockey Perdu, 1941, sold by Dickinson to a Private Collection

The Surrealists, of course, liked nothing better than a game, and specialised in artworks that played tricks on the viewer’s perception of reality. Chess pieces appear regularly in paintings by René Magritte, such as his gouache Le Jockey Perdu, where they loom menacingly, exaggerated in size. And Man Ray’s La Fortune III evokes the Surrealist fascination with chance in the form of a roulette wheel. The roll of toilet paper affixed to the sculpture implies the wiping away of the deceit with which gambling is typically associated.

Man Ray, La Fortune III, 1946-1973, available for sale at Dickinson

Whatever your game of choice while stuck at home recently – chess, solitaire, puzzles or board games – you are part of a longstanding tradition of games in art. Just be glad there’s no cardsharp looming over your shoulder, dagger at the ready!