‘It is easy now to communicate with people through abstraction, and particularly so in sculpture. Since the whole body reacts to its presence, people become themselves a living part of the whole.’

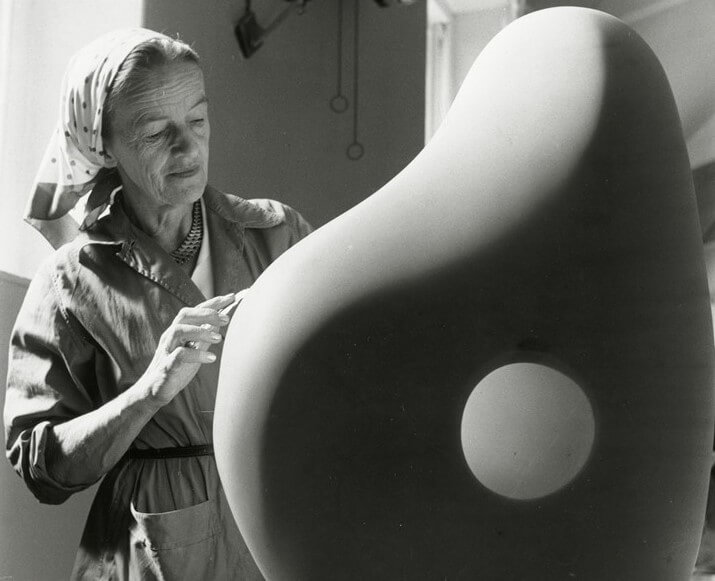

Barbara Hepworth with her Curved Reclining Form (Rosewall) in 1961, photograph by Ida Kar. © National Portrait Gallery

This week, our Artist in Focus insight looks at Dame Barbara Hepworth. As a student, Hepworth earned scholarships to both the Leeds School of Art, where Henry Moore was a fellow pupil, and the Royal College of Art in London, where she tried stone carving for the first time. An early marriage to sculptor John Skeaping had fallen apart by the time she met Ben Nicholson in Norfolk in 1931, and the two were soon married. They enjoyed a lively artistic exchange, and in 1932, Hepworth made her first foray into the pierced forms that would become her trademark. She recalled: ‘I had felt the most intense pleasure in piercing the stone in order to make an abstract form and space; quite a different sensation from that of doing it for the purpose of realism.’

Ivon Hitchens, Irina and Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson and Mary Jenkins on holiday at Happisburgh Beach in 1931

Hepworth and Nicholson left London for Cornwall in 1939 to escape the dangers of the First World War. The couple and their children arrived in St. Ives on 25 August, and, kept busy by the demands of motherhood, Hepworth focused increasingly on her drawings. Inspired by the coastline, she depicted oval and spherical forms, curved and interrupted by hollows or piercings, and crossed with lines that became cords in later three-dimensional translations.

Hepworth in her sculpture garden in St. Ives in 1963

In September of 1949, Hepworth acquired the Trewyn Studio in the centre of St. Ives – now the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden at Tate St. Ives – where she would live and work until her untimely death in 1975. After two decades together, Hepworth and Nicholson separated in December of 1950, although they remained close. Their divorce meant that Hepworth spent more time in her studio, focusing on her sculpture. The 1961 purchase of the Palais de Danse, formerly a cinema and dance hall in St. Ives, provided additional space for her monumental pieces. Meanwhile, Hepworth designed and adapted the Trewyn garden to complement her sculptures, creating an immersive and three-dimensional setting that encouraged visitors to experience the pieces from multiple angles. In 2018, Dickinson dedicated its stand at Frieze Masters to Formed from Nature, a recreation in spirit of Hepworth’s St. Ives sculpture garden, centred on the artist’s monumental bronze River Form (BH 568), conceived in 1965 and cast in 1973.

Dickinson’s stand at Frieze Masters 2018, recreating Barbara Hepworth’s sculpture garden in St. Ives

Hepworth was made a Dame Commander of the British Empire in 1965, the same year she became the first female trustee of the Tate Gallery. In 1968, she was granted Honorary Freedom of the Borough of St. Ives. Hepworth’s studio was opened to the public as a museum in 1976, according to her wishes and bequest. In 2011, the Wakefield Art Gallery in Hepworth’s hometown of Wakefield, Yorkshire, became known as the Hepworth Wakefield in her honour, and this summer the museum will mark the 10th anniversary of this tribute by staging the largest exhibition of Hepworth’s work since her death. This comprehensive retrospective will include loans from both institutions and private collections, and will encompass paintings, drawings and fabric designs as well as sculptures. The show will also feature new works commissioned from contemporary artists Tacita Dean and Veronica Ryan to be exhibited ‘in conversation’ with the pieces by Hepworth.

The Hepworth Wakefield museum, West Yorkshire, UK