To sign or not to sign? And does a signature really add that much value to an artwork? For some collectors it can, providing visible evidence of the artist’s own approval. And they’re not wrong: artists would often sign works when they were satisfied with them. Van Gogh didn’t even wait for his paintings to dry, instead sometimes etching his name into the wet paint with the handle of his paintbrush when happy with the work. Yet not all signatures are created equal, and it is essential to work with a knowledgeable dealer or advisor who can explain the differences.

Among the old masters, many paintings went unsigned, especially in the pre-Renaissance period. Consistency and quality were prized above uniqueness, and it was typical for a master painter to employ a number of able workshop assistants and to take credit for anything that emerged from his studio – no matter how much, or little, of it he executed with his own hand. It was always his name, if any, inscribed on the painting, indicating that the work was produced under his supervision. In the case of many old masters, it is quality of handling rather than the presence or absence of a signature is the most important determiner of value.

Old master drawings were even less frequently signed: historically, they were produced as workshop tools rather than as stand-alone artworks intended for preservation and display. Many of the names we find inscribed on old master drawings today are later additions, and often optimistic ones at that. The initials stamped on a drawing are rarely the artist’s own: it was traditional practice for drawings collectors to stamp their property with a collectors’ mark to indicate ownership.

How can we tell if a signature is a later addition? With a drawing, we can compare it to known examples of an artist’s handwriting, and compare the medium used in the signature to that of the drawing itself. In paintings, we can spot a later signature under fluorescent light, or even with a magnifying glass, if the painted signature is applied on top of the craquelure (age-related cracks in the surface of a painting) rather than beneath it.

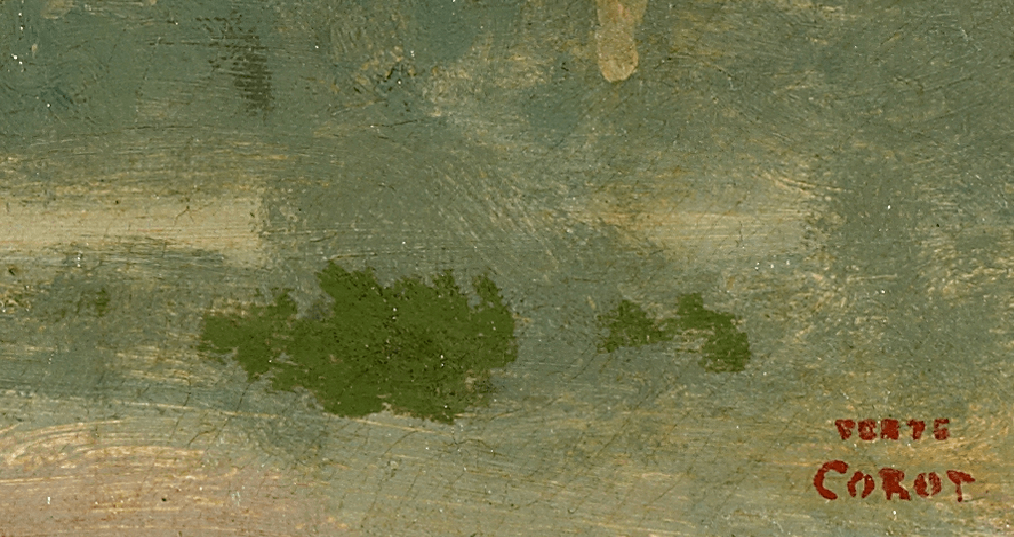

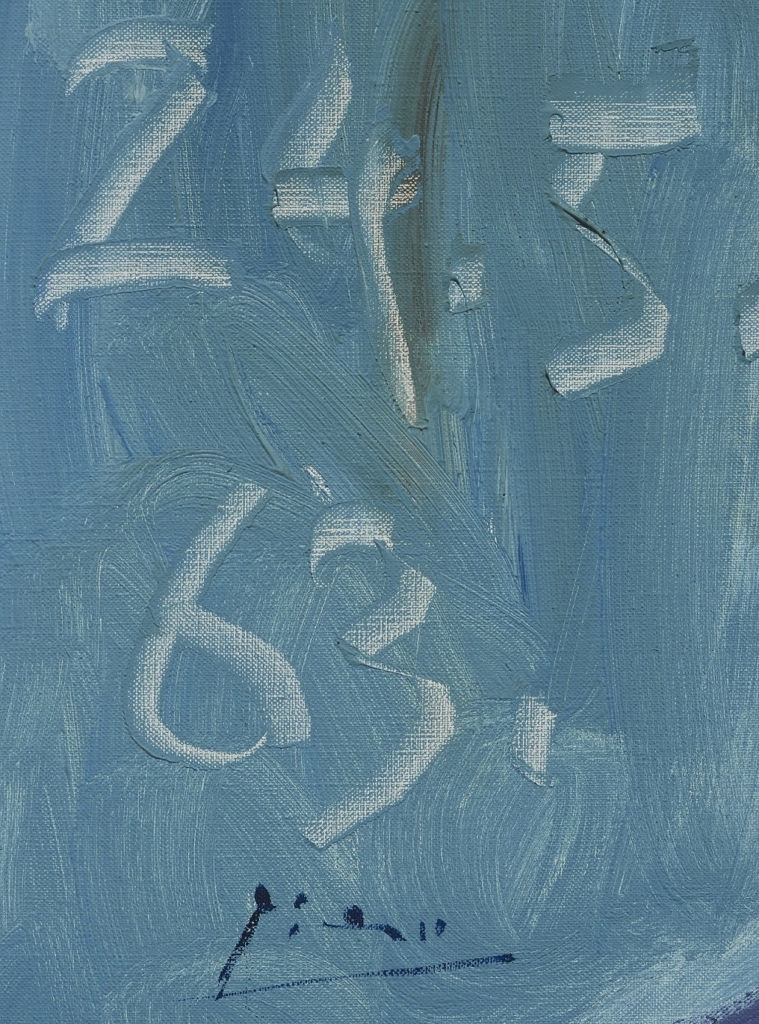

One often sees Impressionist paintings with stamped (rather than handwritten) signatures, evidence that they were left unsigned at the artist’s death and passed through his estate sale. There are many stamped works by Corot, Degas, and Monet, among others. Paintings with stamped signatures are often (albeit not always) less costly than those bearing written signatures, because some of the works remaining in an artist’s studio will inevitably be unfinished, less fully resolved, or sketchier than those paintings the artist elected to sign. Many did not sign their work immediately: in his maturity Picasso, for example, signed works when he was prepared to sell or send them to one of his dealers. He also inscribed them with the date of execution and the initial of the dealer for whom each was destined: ‘R’ on those going to Rosengart, for example, and ‘K’ on those intended for Kahnweiler.

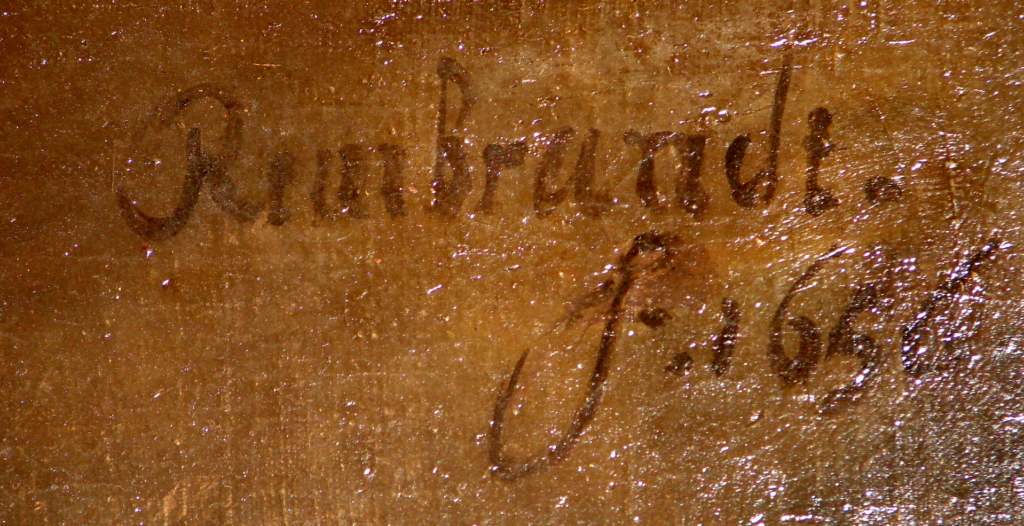

An artist’s signature can sometimes prove useful as a device for dating a work. Some artists remained fairly consistent in their signature style, while others’ signatures evolved over time. When handling a work by one of the latter, experts can narrow down a date for the work in question based on the style of signature. Rembrandt, for instance, signed paintings from the 1620s with initials, while many of his paintings from the following decade are signed with his surname ‘Rembrandt’. And Picasso evolved through a number of signature styles over the course of his lengthy career.

Not all signatures are artists’ names. Some signed their works with symbols: we think of Carlo Crivelli’s cucumber, Whistler’s butterfly, Basquiat’s crown, or Paul Gauguin’s humorous ‘P.Go.’ (a tongue-in-cheek reference to a French slang term). It is even possible, on rare occasions, to find a genuine signature on a spurious painting: very late in Renoir’s life, when his eyesight was failing, unscrupulous owners would ask him to sign paintings they alleged were his own.

The presence – or absence – of a signature on a painting or drawing can tell us a great deal about the artist and his work, but only if we know how to interpret it.