‘I don’t know why I was born in Cuba,’ Herrera once mused. ‘I should have been born in Paris.’ She had become enamored with the city during her finishing school days – memorably taking in performances by Carlos Gardel and a banana-clad Josephine Baker – and it was there, amid the city’s Postwar recovery twenty years later, that she embarked upon an extraordinary journey into abstraction. ‘That was the beginning of the awakening process,’ Herrera acknowledges, and her works from this period betray the sundry origins of her iconic, hard-edged geometry. Thwarted for years following her return to New York – ‘a Cuban? a woman?’ she shrugs; ‘they wouldn’t look at your work’ – Herrera found recognition very late in her career. Today the doyenne of geometric abstraction, she has doubtless claimed her place within the history of Postwar painting, her work featured in major museum collections and celebrated in an acclaimed retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2016.

Herrera’s seminal years in Paris followed periods of study in Havana and then, beginning in 1939, in New York. ‘There were a lot of revolutions – and I mean bloody revolutions,’ she recalls of her adolescence in Cuba. ‘The universities and high schools were closed, but I went to a place called the Lyceum, which was a kind of club that a couple of women had started.’ The institutional haven of Cuba’s historical vanguardia, the Lyceum promoted culture and the arts, offering academic lectures and classes alongside social services and vocational training. Herrera studied sculpture there, under María Teresa Ginerés, in the early 1930s following her return from Paris and before beginning to train as an architect, at the University of Havana, in 1937. ‘There, an extraordinary world opened up to me that never closed,’ she recounts of the two years she spent studying architecture. ‘The world of straight lines, which has interested me until this very day.’ Her education was interrupted by political upheaval as well as her marriage to Jesse Loewenthal, an English teacher at Manhattan’s Stuyvesant High School, and their subsequent departure for New York. Herrera made rounds at the city’s museums and galleries and enrolled at the Art Students League, but she lacked for opportunities – pointedly, she was excluded from the landmark exhibition, Modern Cuban Painters (Museum of Modern Art, 1944) – and missed the receptive community of artists that she had known in Havana.

‘We went to Paris as soon as we could after the war,’ Herrera reminisces. ‘It was a very happy time in my life – I was young, I had a wonderful husband whom I loved. . . . Paris at that time was like heaven.’ Arriving in June 1948, they soon moved into a studio in Montparnasse – in the same building, on rue Campagne-Première, as Yves Klein’s parents – and immersed themselves in the incandescent café culture of the Left Bank, circulating among artists (Arman, Serge Poliakoff, Jean Tinguely) and writers (Eugène Ionesco, Jean Genet). Herrera participated in a number of group exhibitions, including Art cubain contemporain (Musée National d’Art Moderne, 1951), organized by the Cuban Concretist Loló Soldevilla, and the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, a bastion of Postwar geometric abstraction founded in 1946. ‘The exhibition was a response to the Nazi’s anti-modern stance, and here you had the many voices that the Third Reich tried to silence; it was powerful,’ Herrera explains. ‘Everything that was in the exhibition was abstract, geometric, even pre-minimal. Albers’ paintings touched me. I was able to see more work by the Bauhaus. I felt that this was the kind of painting that I wanted to do. I had found my path as a painter.’ The Salon championed a diverse roster of abstract artists, and Herrera encountered the legacy of the School of Paris – represented by her teacher and the Salon’s creative force, Auguste Herbin, as well as Jean Arp and Sonia Delaunay – in addition to an international field that included Jesús Rafael Soto, Alejandro Otero, Victor Vasarely, and Ellsworth Kelly. ‘You would go in and show your painting, and they’d either accept it or not,’ Herrera recounts of the Salon. ‘One of the founders of the group [Fredo Sidès] said to me, “Madame, but you know you have so many things in that painting,” and I felt very good about the compliment. But then I realized that he was trying to tell me that I was putting too much in the painting.’

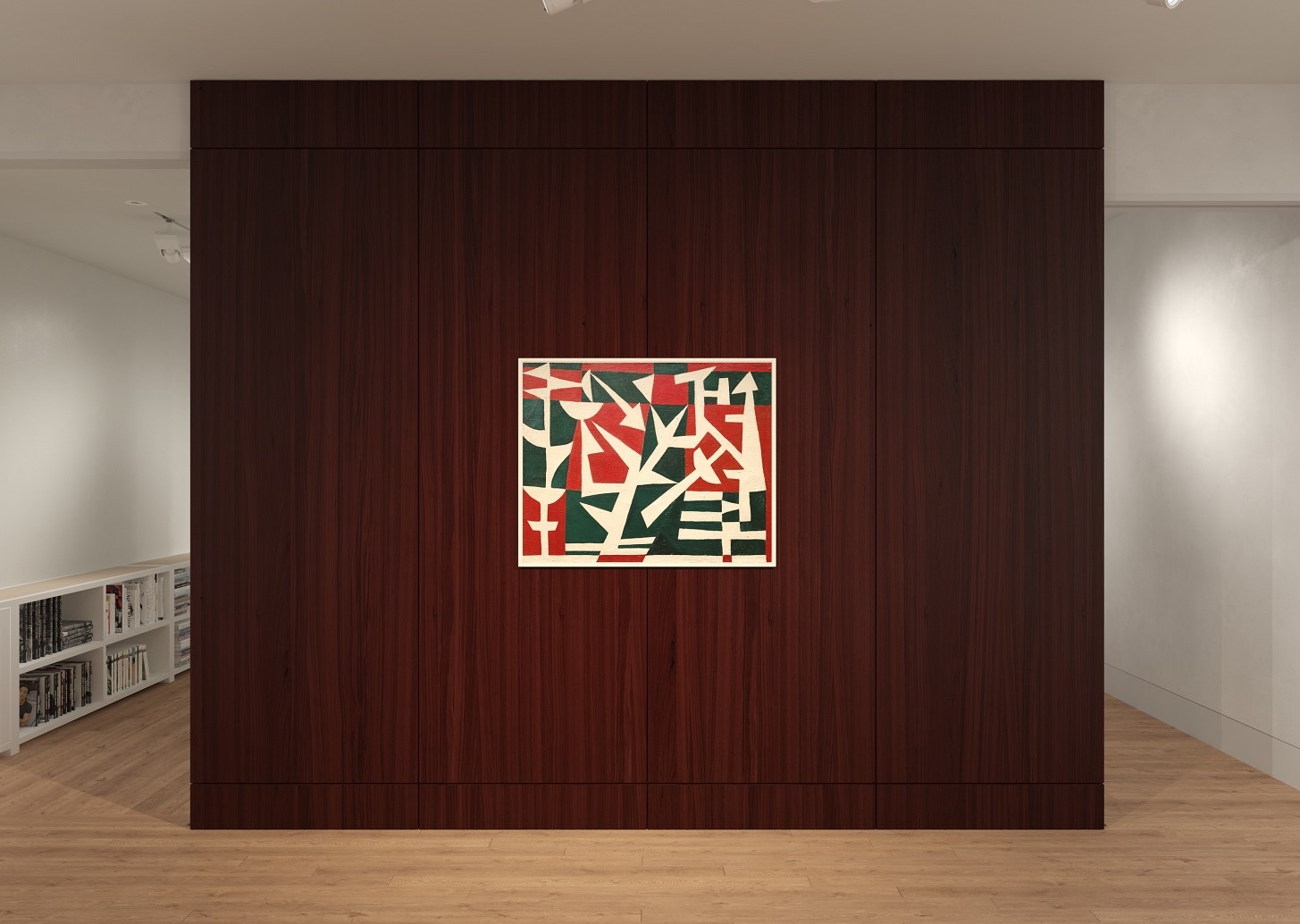

The early critique accelerated the minimalist direction of her work, which began to shed the biomorphic and gestural lyricism best seen in the Habana Series (1950-51), made during holiday visits to the island. […] Herrera experimented with concrete geometries as early as Venetian Red, White and Black (1949), reducing her palette to three austere colours and exploring the interplay of figure and ground. She reprised this progression in the dramatic Field of Combat (1952), in which the white blocks acquire angles – arrows – and allusive meaning. As in contemporary work by Wifredo Lam, Mario Carreño, Luis Martínez Pedro, Herrera’s triangles and crescent shapes have a source in Afro-Cuban ritual and symbology; marshaled dynamically here, they may also acknowledge the gravity of Fulgencio Batista’s coup d’état in March 1952 and the beginning of the dictatorship that would end in the Cuban Revolution. Field of Combat numbered among the paintings that she showed at Galería Sudamericana in 1956, her first solo exhibition in New York. Noting Herrera’s relationship to ‘the French concrete school’ and praising her ‘high, original colour,’ Dore Ashton declared her ‘one of Cuba’s best non-objective painters.’

‘There’s a saying that you wait for the bus and it will come,’ Herrera recently observed. ‘I waited almost a hundred years!’ Increasingly recognized as one of the best non-objective painters the world over, she continues to work from the Gramercy loft where she has lived since 1967, her practice still building upon principles first articulated in Paris. ‘I do it because I have to do it; it’s a compulsion that also gives me pleasure,’ Herrera reflects these days of painting. ‘I never in my life had any idea of money and I thought fame was a very vulgar thing. So I just worked and waited. And at the end of my life, I’m getting a lot of recognition, to my amazement and my pleasure, actually. . . . Only my love of the straight line keeps me going.’

Excerpted from the introduction by Dr. Abigail McEwen, Associate Professor of Latin American Art at the University of Maryland, to the catalogue of Carmen Herrera in Paris: 1949 – 1953 at Dickinson New York, 2 November 2020 – 8 January 2021.