ITALIAN SHOW

January 29th – February 28th 2014

Dickinson is delighted to present Italian Show, an exhibition featuring selected works by Post-War andContemporary Italian artists. Together, the exhibition represents some of the most significant artistic movements and attitudes of the second half of the 20th century, all of which sought to contribute to the utopian protests of the late 1960s.

The rupture with the modernist tradition began in the 1950s with the development of an art that was seeking a dynamic new mode of creation. By early 1960s, the most prominent Italian artists had departed drastically from the traditional canon. Alberto Burri, Lucio Fontana and Piero Manzoni reached beyond the limits of painting in their employment of unusual materials and innovative techniques, thereby pushing the boundaries of the canvas. Alberto Burri created his earliest works while imprisoned during the Second World War, an experiment that later led him to attack his canvases with burnt or raw materials, cut and sewed up like physical wounds. Lucio Fontana challenged the traditional flat surface of the canvas by slashing (Tagli) and puncturing (Buchi) the canvas, in an effort to create a window open to infinity and to what lies behind the opaque planarity. After discovering Yves Klein’s monochrome works, Piero Manzoni focused from 1957 onwards on his Achromes, white canvases covered with glue and kaolin on which he formed shapes using pleats and the natural texture of the canvas. Together with Agostino Bonalumi and Enrico Castellani, Manzoni founded the Azimuth Gallery in Milan, which was connected to Germany’s Gruppe Zero. Founded by Heinz Mack, Otto Piene and Günther Uecker, Gruppe Zero had similar concerns about the necessity of achieving emancipation from the artistic traditions of gesture painting. Yet another member of the Azimuth Gallery group was Dadamaino, whose Volumi featured large elliptical holes in canvases which then became frames for the voids, ultimately responding to her ongoing quest for immateriality. Turi Simeti followed in the footsteps of Bonalumi with his work on the concept of the painting-as-object. By incorporating ellipsoid elements pressed against the back of his canvas, he was able to create movement, and contribute further to ongoing artistic efforts to manipulate and reform the surface. Other artists such as Alberto Biasi pushed the boundaries of traditional art by transforming geometrical shapes into optical-kinetic, which takes its name from the optical illusions it creates. As a group, these artists exerted a strong impact on succeeding generations, and specifically on the spirit of Arte Povera. Arte Povera was an attitude rather than a movement, as the latter would have narrowed its actors to a definition. Members of the Arte Povera group shared a socially and politically engaged attitude that can be defined as a rejection of the industry of culture and more generally of the society of consumption.

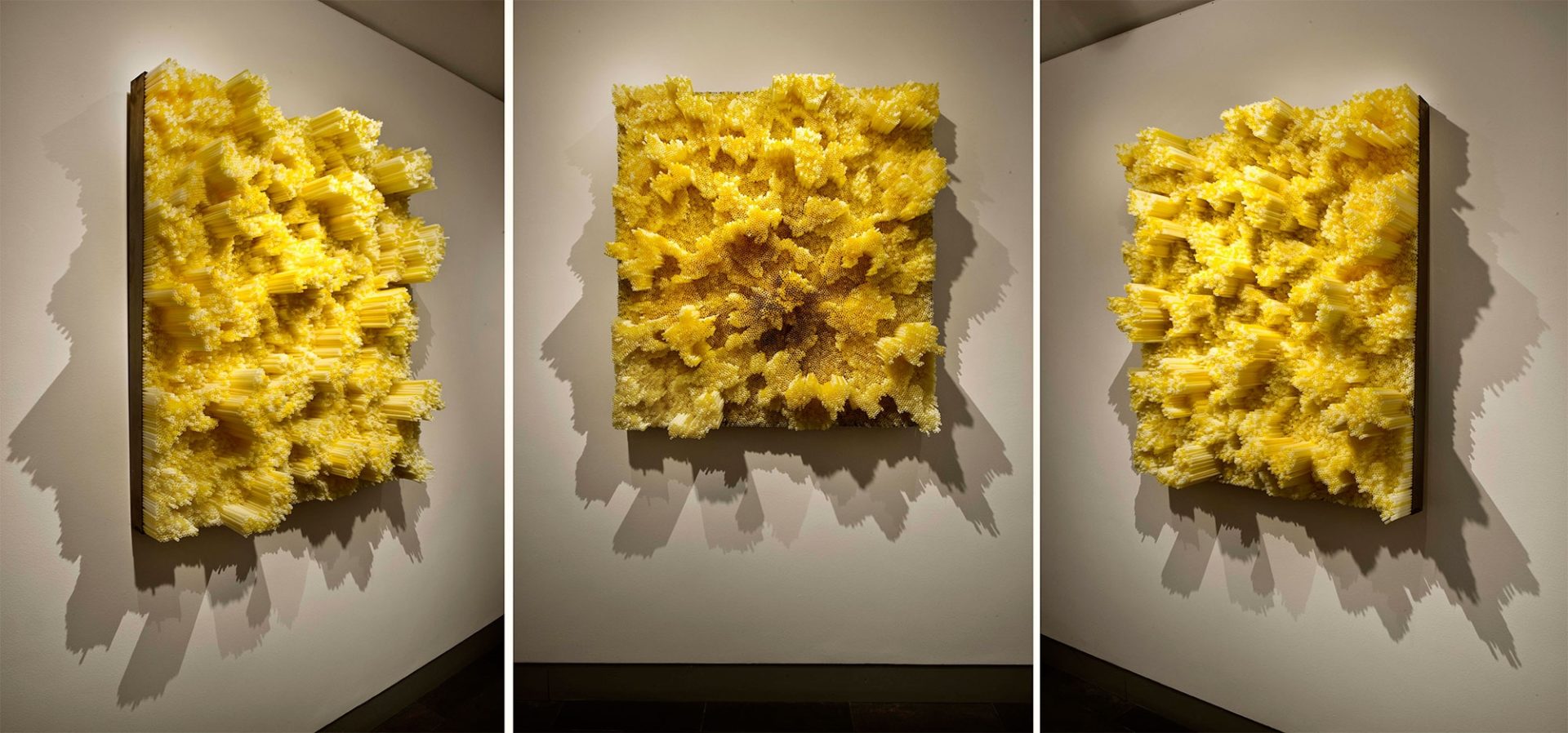

This engagement found its artistic form in the process of creation rather than in the finished object. By condemning identity and object, Arte Povera artists became completely elusive. The expression “Arte Povera” was used for the first time in September 1967 by Germano Celant to characterize an exhibition held in Genoa. “Povera” traditionally refers to the use of humble materials, though this definition has since been contested by scholars who argue that the term refers instead to simpler creative techniques, as contrasted with the intensely theoretical concepts behind the works. The Italian Show includes works by a number of artists who embraced this way of thinking. Michelangelo Pistoletto and his mirror pieces reflect the form and movement of the viewer and his environment. Alighiero Boetti whose embroidered works with their varied colours and forms, reference the evolving worldwide geopolitical situation. Pier Paolo Calzolari demonstrates his enduring fascination with the pure whiteness of frost as subject. More recently Mario Ceroli who employs burnt wood as a favourite medium, advocates a return to the origins of craftsmanship. Not all Italian artists responded favorably to the prevailing attitudes of Arte Povera. Domenico Gnoli elected to create paintings that magnified details of clothing or furniture, emphasizing the growing importance of materiality. His aesthetic was a direct protest against those artists who prized simplicity. Mimmo Rotella pursued a different direction yet again, and his work approaches that of the Nouveau Réalisme movement in France and the Affichistes. Finally, a new generation of Italian artists remain very much influenced by mid-20th century theories, as demonstrated by Francesca Pasquali, who seeks to challenge the way we see everyday objects by removing their original functions and focusing instead on their pure aesthetic forms.