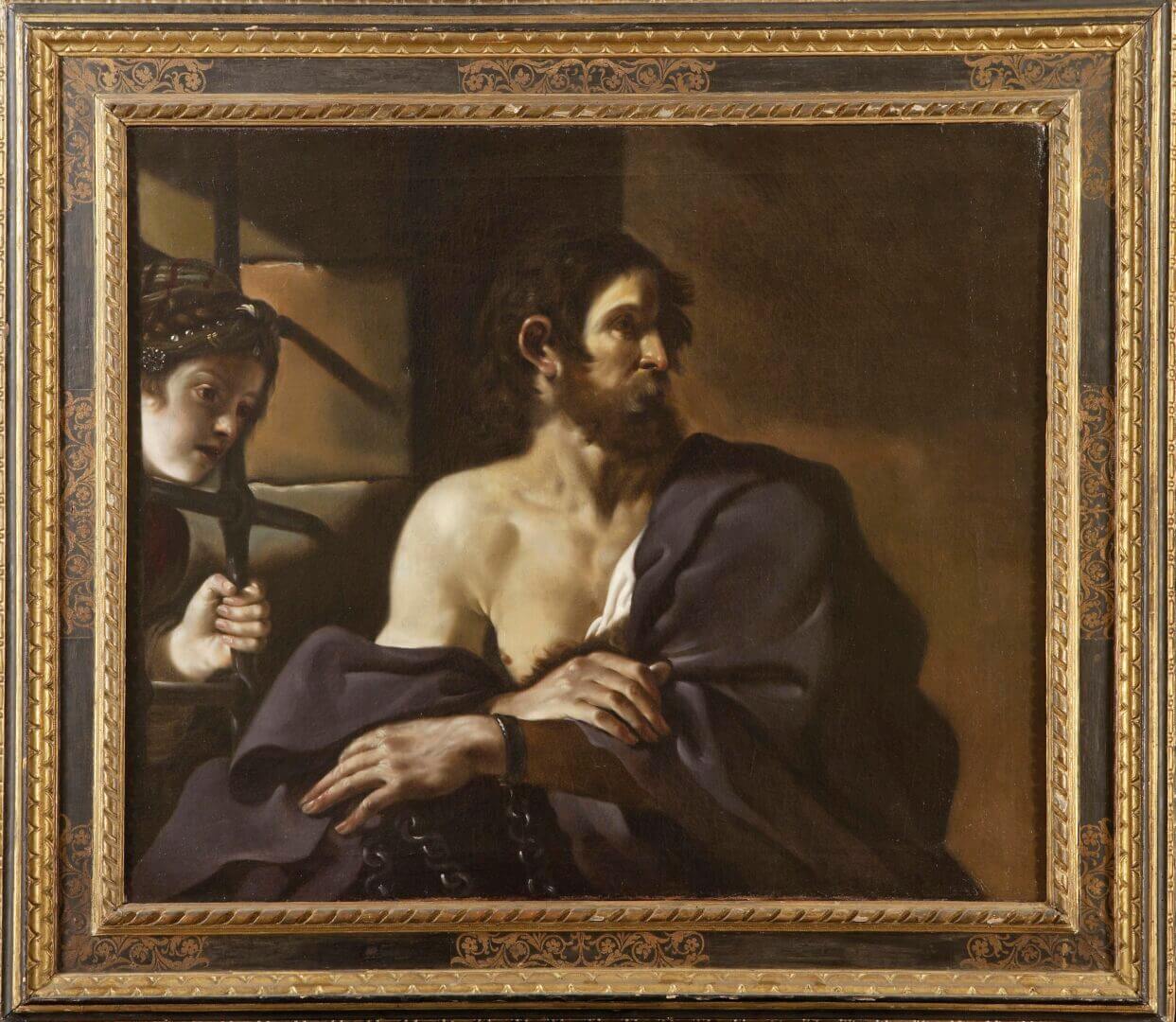

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, called il Guercino

Saint John the Baptist in Prison with Salome looking on

Old Masters

Provenance:

Stefano Bardini, Florence.

His sale; The American Art Association, New York, 23-27 April 1918, 3rd day, lot 469 (as ‘Spanish School, 17th Century’).

The Diocese of Marquette, Michigan, USA (in the Bishop’s Residence).

Private collection, UK.

Literature:

N. Turner, The Paintings of Guercino: A revised and expanded catalogue raisonne, Rome, 2017, p. 358, under no. 99.III (as a copy, on the basis of photographs. Mr. Turner has since inspected the painting first-hand and will include it in his forthcoming supplement to the catalogue as an autograph work by Guercino.)

Engraved:

Pietro Savorelli, 1786.

Damiano Pernati, 1799.

In this work Guercino depicts Saint John the Baptist in prison, where he was incarcerated for his criticism of King Herod’s marriage to his brother’s wife, Herodias. John is visited by Herodias’s daughter, Salome, who peers through the prison bars at left. It was Salome who would later, at her mother’s request, ask Herod for Saint John’s head on a platter as a reward for her dancing. Often represented as a beguiling temptress, she here appears tentative and uncertain, looking anxiously at the saint while he stares resolutely in the opposite direction.

The subject of Saint John in prison is mentioned in three documents relating to Guercino’s artistic activity. A picture described as ‘San Giovanni Battista con Erodiada’ appears in the will of Stefano Scaruffi of Reggio Emilia (dated 28 July 1621), described as ‘donatomi dal pittore Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, deto il Guerzino di Cento’. A picture representing the same subject (‘San Giovanni in carcere, mezo quadro bislongo, del Guerzino da Cento’) is listed in the inventory of Bishop (Marchese) Paolo Coccapani of Reggio Emilia (3 Dec. 1647). And, finally, there is the painting mentioned in a note sent circa 1670 to the Sicilian collector Don Antonio Ruffo, probably from his agent in Rome, Abraham Brueghel. That work is described as ‘Del Guercino di p.ma maniera di 3 p.mi S.Gio. in prigione con una Donna che lo tenta’.

In addition to our picture, two other versions of Saint John the Baptist in prison visited by Salome were accepted as autograph by Sir Denis Mahon, and some scholars now believe there to be a total of five. There are also a number of studio and later copies, evidence that the composition was widely admired in the 17th century. Scholars agree that the prime version, which shows numerous pentimenti, is that in a private collection in New York (sold Sotheby’s, London, 8 April 1981, lot 70). It is generally dated to circa 1618-21. Salerno (Dipinti del Guercino, Rome, 1988, no. 65) associates the New York version with that mentioned in the Scaruffi will.

More recently, a newly-discovered version was offered at Sotheby’s (New York, 29 Jan. 2009, lot 57), and scholars have accepted this as a second autograph version, with the attribution endorsed by Prof. David Stone, Dr. Erich Schleier, Prof. Mina Gregori, Nicholas Turner and Sir Denis Mahon, all of whom inspected that painting first-hand. Prof. Andrea Emiliani, who commented on the basis of photographs, also supports the attribution to Guercino. It is considered nearly contemporary with the New York version, and stylistically it is entirely consistent with other works painted by Guercino shortly before he left for Rome in May 1621. (While still in his twenties, Guercino earned the patronage of two significant collectors in Rome: Cardinal Scipione Borghese and his great rival, Cardinal Alessandro Ludovisi, Archbishop of Bologna. The latter called Guercino to Rome shortly after he was elected Pope Gregory XV in February 1621.) This version also reveals in x-ray analysis an image of Saint Matthew and the Angel beneath the St. John, a composition that appears to be by Guercino’s hand as well.

Mahon’s own version of the Guercino St. John (on loan to the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin), which he deemed an autograph replica, was dated by Mahon and other experts to the mid 1620s. Schleier and Stone have suggested that it was a product of Guercino’s workshop, albeit one of high quality. This is the picture once owned by Lord Radstock (1753 – 1825), which subsequently entered the collection of the Marquess of Lansdowne. It is likely, according to Mahon, that it was in the Borghese collection in Rome until around 1800, as there is an engraving of the composition by Pietro Savorelli dated 1786. (Radstock owned a second ex-Borghese painting, also by Guercino.) Mahon himself proposed, on the assumption that Salerno’s identification of the New York picture with the Scaruffi painting is correct, that his version was painted in Reggio in 1624-26, and is therefore the one mentioned in the Coccapani inventory. Marchese Paolo Coccapani, who arrived in Reggio as Bishop on 12 May 1625, was a collector from Ferrara and a great admirer of Guercino’s work. It is very probable that, shortly after his arrival, he requested and was given an autograph replica of the Scaruffi painting, executed during one of Guercino’s previous visits. (The authors of the Reggio catalogue of 1982, unaware of the existence of the New York painting, assumed that the Scaruffi and Coccapani paintings could be identical, but there is no evidence to support that assumption. Coccapani’s collection was transferred to Modena after his death in 1650, having been inherited by his nephew the Marchese Alfonso Coccapani, and it was subsequently dispersed.)

What we know about Guercino’s commissions in Reggio substantiate the argument that he painted the version for Coccapani some time between 1624 and 1626. Guarcino was in Reggio on 8 May 1625, at which point he received payment for his large altarpiece of the Crucifixion for the church of the Madonna della Ghiara (N. Artioli and E. Monducci, Le Pitture di San Giovanni Evangelista in Reggio Emilia, Milan, 1978, pp. 146-48, doc. LXI). The following day, he was contracted to paint an altarpiece of the Assumption for the Cathedral, in honour of Coccapani’s appointment (N. Artioli and E. Monducci, op. cit., pp. 148-51, doc. LXII). By 9 September, Guercino had returned from Reggio to Cento, and he was back the following May to deliver the completed altarpiece. If, however, as Schleier and Stone have suggested, Mahon’s own version is a studio work, the Coccapani inventory must refer to one of the other autograph versions.

The third document recording a St. John subject by Guercino is the 1670 note to Ruffo from his agent in Rome. Mahon originally questioned the accuracy of the given measurement of 3 palmi (67 cm.) on the grounds that none of the versions known to him conformed to these smaller dimensions (D. Mahon, Il Guercino: dipinti, Bologna, 1968, pp. 123-24, no. 52). He suggested that the unreliability of seventeenth-century measurements might allow us to conclude that the reference could relate to the present painting. However, the version offered at Sotheby’s in 2009 was somewhat reduced in size (75 x 96 cm.), and that seems the more likely candidate. (Since Mahon’s analysis, yet another version has appeared at auction, at Semenzato, Venice, 2 May 2004, lot 94. However this picture was of larger dimensions, measuring 81.5 by 99.5 cm.)

Stylistic evidence indicates, again according to Mahon, that the present version was executed during the latter half of Guercino’s Roman stay, around 1622-23. Mahon and Pepper compare the handling to that seen in Guercino’s monumental altarpiece of Santa Petronilla painted for Saint Peter’s in 1622-23, particularly in the heads and hands of the male figures on the right, which relate to the head and hands of Saint John. Mahon also observed a connection with the Saint Matthew and the Angel in the Capitoline Gallery, Rome, which likewise dates from around 1622. The present work is the largest in size of the St. John paintings by Guercino, measuring some ten centimetres higher and eleven centimetres wider than either the New York or Mahon version. The popularity of the theme, testified to by the numerous copies, explains the existence of multiple autograph versions. Furthermore, there is a precedent for the artist having executed three nearly identical versions of a composition in fairly close sequence: the three versions of The Ecstasy of Saint Francis (National Museum, Warsaw; Fava collection, Cento; and Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden). A preparatory drawing in black chalk by Guercino in the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo may be a study for the head of Salome. Mahon believes that a drawing of St. Peter in Prison, Writing and Speaking to a Youth Outside (pen and ink; Princeton University Art Museum, inv. no. 59.36) may represent a first idea for the composition.

This picture once belonged to Stefano Bardini, the well-known Florentine art dealer and restorer, whose collection was dispersed at a sale in New York in April 1918. At the time, it was sold as an image of The Roman Daughter by an unknown 17th century Spanish master. The catalogue was compiled by Horace Townsend (De Luxe Illustrated Catalogue of the Beautiful Treasures and Antiquities Illustrating the Golden Age of Italian Art Belonging to the Famous Expert and Antiquarian Signor Stefano Bardini of Florence, Italy) and the painting was illustrated in its current frame. We are grateful to Dr. Everett Fahy of the Department of European Painting at the Metropolitan Museum for kindly sharing this information with us (written communication, 8 July 1999). Much of the information for this note was compiled in 1999 by Dr. D. Stephen Pepper, in collaboration with Sir Denis Mahon. Both scholars examined the present painting first-hand, and declared it to be an autograph work by Guercino. Dr. Erich Schleier, who has also examined the work first-hand, endorses this attribution (verbal communication, March 2001). Nicholas Turner considers it autograph and will include it in his forthcoming supplement to the recently published catalogue raisonnéof Guercino’s work (based on first-hand inspection, 6 Dec. 2017). In his catalogue, Turner points out that it was only recently that scholars began to accept that Guercino repeated his compositions. Professor David Stone, who also inspected the work first-hand, believes it to be by a follower of Guercino (verbal communication, Oct. 2016).