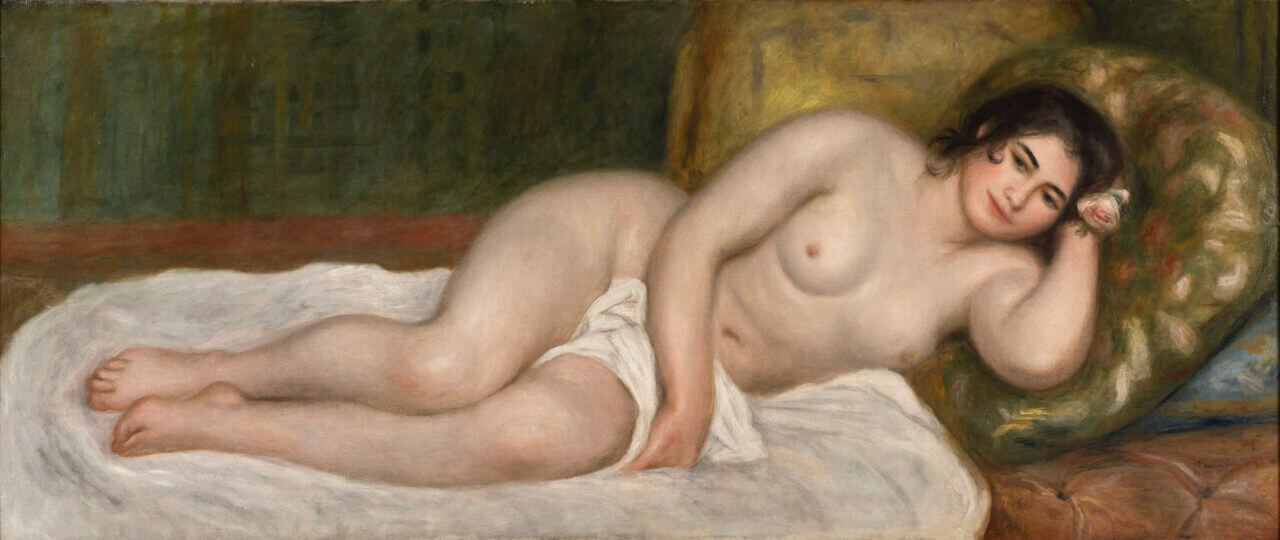

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Femme nue couchée (Gabrielle), 1903

Historic Sales

Provenance:

Galerie Durand-Ruel et Cie, Paris, acquired from the artist on 18 July 1907.

Private Collection, acquired from the above on 22 Nov. 1917 at the Hague exhibition.

Maximilian von Goldschmidt-Rothschild (1843 – 1940), Berlin, by 1926.

Jos Hessel (1859 – 1942), Paris.

Durand-Ruel Galleries, New York, acquired from the above on 12 Aug.

M. Knoedler & Co., Inc., New York, sometime after 1946.

George Embiricos, Lausanne.

Anon. sale; Christie’s, New York, 16 May 1977, lot 32 ($660,000).

Raymond & Miriam Klein, Philadelphia, PA.

Their Estate Sale; Christie’s, New York, 4 May 2010, lot 34 ($10,162,501).

Private Collection, acquired at the above sale.

Literature:

J. Meier-Graefe, Auguste Renoir, Paris, 1912, p. 176.

H.P. Bremmer, ed., Beeldende Kunst, Berlin, 1920, issue 18 (illus.)

G. Rivière, Renoir et ses Amis, Paris, 1921, p. 132 (illus.)

P. Jamot, ‘Renoir’, in Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Paris, 1 Dec. 1923, p. 322 (illus.)

A. Vollard, Renoir, An Intimate Record, New York, 1925, p. 245.

The Arts, Jan. 1927, p. 45.

A. André, Renoir, Paris, 1928 (illus. pl. 36).

J. Meier-Graefe, Renoir, Leipzig, 1929, p. 289, no. 297 (illus.)

Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum, vol. 29, no. 158, Dec. 1933, p. 20 (titled Reclining Nude, lent by Durand-Ruel).

The Art News, 16 Dec. 1933 (illus.)

A. André, ‘Renoir et ses modèles’, in Le Point, Paris, Jan., March, May and Oct. 1936.

‘Art through America’, in Art News, New York, 28 March 1936, p. 12.

Parnassus, New York, 1 April 1936, p. 27.

M. Florisoone, Renoir, Paris, 1938, p. 143 (illus.)

M. Davidson, ‘Poetic Visions of the late Renoir’, in Art News, New York, 1 April 1938, p. 22.

S. Rocheblave, French Painting of the XIXth Century, New York, 1941, p. 72 (illus.)

D. Brian, ‘This Century’s Share of Renoir’, in Art News, New York, 1 April 1942, p. 33.

P. Laporte, ‘L’art classique de Renoir’, in Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Paris, March 1948, p. 180 (illus.)

Strange, Renoir, Berlin, n.d., p. 5.

J. Baudot, Renoir, ses Amis, ses Modèles, Paris, 1949, p. 66.

D.E. Gordon, Modern Art Exhibitions 1900 – 1916, Munich, 1974, pp. 139, 237 and 534.

Hoog and H. Guicharnaud, Musée de l’Orangerie: Catalogue de la collection Jean Walter et Paul Guillaume, Paris, 1984, pp. 212-13 (illus.)

B.E. White, Renoir, his Life, Art, and Letters, New York, 1984, p. 229 (illus.; incorrectly dated 1905-06).

House, A. Distel and L. Gowing, Renoir, exh. cat., Hayward Gallery, London, 1986, pp. 271-72, no. 101 (illus., p. 271; illus. in colour p. 152).

J.B. Jiminez, ed., Dictionary of Artists’ Models, London, 2001, p. 450 (incorrectly dated 1905-06).

J. House et al., Renoir aux XXe siècle, exh. cat., Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris, 2009, p. 252, fig. 97 (illus. in colour).

Einecke, S. Patry et al., Renoir in the 20th century, exh. cat., Grand Palais, Paris, 2009, p. 252, no. 97.

G.P. and M. Dauberville, Renoir, catalogue raisonne des tableaux, pastels, dessins et aquarelles, Paris, 2012, vol. III, 1903-10, p. 489, no. 3502 (illus.)

Exhibited:

Paris, Grand Palais, Le Troisième Salon d’Automne, Peintures, Dessins, Sculptures, Gravures, 18 Oct. – 25 Nov. 1905, no. 1321 (as Femme nue).

Budapest, Nemzeti Salon, Modern francia Nagymesterek Tárlata, 1-31 Dec. 1907, no. 3 (as Pihenö asszony, 44,000 ffr).

Brussels, La Libre Esthétique, Salon jubilaire, 1 March – 5 April 1908, no. 157.

St. Petersburg, Palais Youssoupof, L’Institut Français, Exposition Centenniale de l’Art Français, 1 Jan. – 31 Dec. 1911, no. 538 (as ‘Femme couchée, coll. Durand-Ruel, Paris’).

The Hague, Panorama-Mesdag, Exhibition of French Art, Dec. 1916 – Jan. 1917, no. 87.

New York, Durand-Ruel Galleries, The Impressionists, 1 Jan. – 31 Dec. 1926, no. 19.

New York, Durand-Ruel Galleries, Paintings by the Master Impressionists, April 1929, no. 14.

Chicago, IL, The Arts Club, Paintings by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 7-26 Nov. 1930, no. 11.

New York, Durand-Ruel Galleries, Paintings by Renoir since 1900, 21 Nov. – 10 Dec. 1932, no. 14.

Philadelphia, PA, The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Manet and Renoir, 1 Nov. 1933 – 31 Jan. 1934, n.n.

Chicago, IL, The Art Institute of Chicago, A Century of Progress: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, 1 June – 1 Nov. 1934, no. 233.

Kansas City, MO, The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and The Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, One Hundred Years of French Painting, 1820 – 1920, 31 March – 28 April 1935, no. 49.

Colorado Springs, CO, Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, Retrospective Exhibition, Modern French Painting, 1 April – 30 June 1936, no. 12.

New York, Durand-Ruel Galleries, Renoir, 19 Oct. – 14 Nov. 1936, no. 1.

Philadelphia, PA, The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Renoir – Later Phases, 16 April – 19 June 1938.

San Francisco, CA, Palace of Fine Arts, Golden Gate International Exposition, 25 May – 29 Sept. 1940, no. 298.

New York, Duveen Galleries, Renoir Centennial Loan Exhibition, 8 Nov. – 6 Dec. 1941, no. 72 (loaned by Durand-Ruel).

New York, Durand-Ruel Galleries, Exhibition of Masterpieces by Renoir after 1900, 1-25 April 1942, no. 15.

New York, Durand-Ruel Galleries, Nudes by Degas & Renoir, 10 April – 5 May 1945, no. 12.

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Summer 1962 (on extended loan).

London, Hayward Gallery, Renoir, 30 Jan. 1985 – 21 April 1985, no. 99; this exhibition later travelled to Paris, Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, 14 May – 2 Sept. 1985; and Boston, MA, Museum of Fine Arts, 9 Oct. 1985 – 5 Jan. 1986 [not exhibited in Boston].

Paris, Grand Palais, Renoir au XXe Siècle, 23 Sept. 2009 – 4 Jan. 2010, no. 101; this exhibition later travelled to Los Angeles, CA, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 14 Feb. – 9 May 2010; and Philadelphia, PA, The Philadelphia Museum of Art, 17 June – 6 Sept. 2010.

This work is accompanied by a certificate from the Wildenstein Institute dated 5 March 2010 and numbered 10.03.05/11117. It also includes a letter of authenticity from Bernheim-Jeune dated 28 April 2010, signed by Guy-Patrice and Michel Dauberville. This work is accompanied by an Attestation of Inclusion from the Wildenstein Institute and will be included in the forthcoming Renoir Digital Catalogue raisonné, currently being prepared under the sponsorship of the Wildenstein Plattner Institute, Inc.

‘But his nudes…the loveliest nudes ever painted: no one has done better – no one.’ (Henri Matisse)

Introduction:

‘It was by his images of women that Renoir wished to be judged as an artist. His late works, in which the resplendent nudes represent a mythical ideal of woman…are a fitting final testament’ (A. Dumas, Renoir’s Women, Columbus, 2005, p. 85).

Renoir’s great nudes belong to his final period, when the artist – by that point a successful and widely admired elder statesman of Impressionism – was free to paint what he wished without being limited by financial concerns. Having begun his career as a painter of porcelain and fans in the 1850s, Renoir made his name as a portraitist and chronicler of the Parisian bourgeoisie, as well as an especially able painter of children. The women who populate his paintings are of a similar type, whether they are individuals or idealised: plump, rosy-cheeked, healthy and cheerful. Renoir’s late nudes conform to this preference, although they are also – on a whole – classically inspired and as timeless as his Parisian portraits are contemporary and fashionable. Throughout his career Renoir preferred painting women; indeed, almost no men at all appear in his paintings after 1886. The relationships he forged with his favourite models, including his wife Aline and Gabrielle Renard, the principal model and muse of his final years, led to many of his late masterpieces. In Femme nue couchée, Renoir combines his interests in Orientalism, the idealised nude, and historical precedents to produce a monumental and sensuous portrait.

Renoir and the Nude:

‘I like a painting which makes me want to stroll in it, if it is a landscape, or to stroke a breast or back, if it is a figure’ (Renoir)

In the late 1880s and 1890s two distinct strands of subject matter dominated Renoir’s output. On the one hand he continued to paint scenes of domestic harmony that reflected his deepening relationship with Aline Charigot, who had been his model and companion for more than a decade when he married her in 1890. He also addressed his experiences of fatherhood and family life: Pierre, the first of his three sons, was born in 1885; Jean arrived in 1894 and Claude was born in 1901.

It was during the same period that Renoir turned with renewed enthusiasm to the subject of nude bathers. Like Fragonard, Boucher and Rubens before him, Renoir was drawn to scenes of attractive girls in bucolic settings, singly or in groups, which celebrated the beauty of the female form amid the abundance and fertility of unspoiled nature. Beginning in the 1890s he produced a number of reclining nude figures set against landscape backgrounds: Nu couchée, executed in 1895, established his conception of the reclining nude in a horizontal format. He reprised this subject in La Source: Nu allongé, painted in 1902, a year before Femme nue couchée.

Renoir also experimented with reclining nudes in an interior setting, viewed from both the front and the back. Unlike his images of bathers outdoors, which explore the soft colour effects and patterns of light and shade on the female form, Renoir’s interior nudes focus on the shape of the figure itself, while the setting diminishes in importance. The models in these interior compositions often recall the odalisques of Orientalist harems. Renoir had addressed this subject much earlier in his career: in 1870 he painted Femme d’Alger (Odalisque), featuring a young woman dressed in elaborate North African costume reclining in a tapestry-draped interior. With the freedom afforded by a more reliable income, Renoir travelled twice to Algeria, in 1881 and 1882, and memories of these trips continued to inspire his work in later years.

The horizontal format of Femme nue couchée and other works from this period may have been partly the consequence of a painful physical limitation: while riding his bicycle in Essoyes on a rainy day in early September 1897, Renoir skidded and fell, breaking his right arm. Although the fracture eventually healed, he began to suffer from shooting pains in his right shoulder due to the onset of muscular rheumatism and arthritis. Left unable to raise his right arm above shoulder level, he preferred to paint on horizontal canvases when working in large format, until a system of trestles devised for his chair enabled him to return to larger vertical compositions.

Historical Precedents:

‘The limpidity of that flesh, one wants to caress it. In front of this painting one feels all the joy that Titian had in painting it. That old Titian…he even looks like me, and he’s forever stealing my tricks.’ (Renoir)

Having visited the Louvre regularly from an early age, Renoir maintained a lifelong interest in the old masters, often borrowing poses or concepts from his predecessors. As scholar Martha Lucy has pointed out, many of Renoir’s nudes adopt poses borrowed from Jean Goujon’s stone reliefs for the base of the Fontaine des Innocents, subsequently installed in the Louvre. In 1892, Renoir visited the Prado in the company of his friend the publisher Paul Gallimard, and he had the opportunity to admire works by Goya and Velázquez. But it was one reclining nude by Titian that particularly captivated him, the Venus with Cupid and an Organist. Renoir later remarked to the dealer Ambroise Vollard: ‘Ah, Titian has everything. First, mystery; then depth…In the Venus and the Organist the limpid quality of that glowing flesh is fairly alive. You actually feel the joy he had in painting it…I have really lived a second life through the pleasure I have had from the work of the masters’ (quoted in A. Vollard, Renoir: An Intimate Record, New York, 1925, p. 62). In painting Femme nue couchée, Renoir sought to emulate the glowing skin of Titian’s reclining Venus, accomplished through the translucent layering of thin glazes of paint. Renoir was also captivated by French Rococo art, whose characteristic pastel palette, lighthearted subject matter and brushy handling of paint is often mirrored in Renoir’s own work.. He once declared: ‘I am of the eighteenth century. I humbly consider not only that my art descends from Watteau, Fragonard, Hubert Robert, but that I am one of them’.

The old masters were not Renoir’s only source of inspiration, and we see direct parallels with more contemporary examples of reclining nudes. Ingres’ harem girls, such as L’Odalisque à l’Esclave, were exhibited to great acclaim in Paris, while Gérôme’s exotic fantasies of Turkish bathers earned him a considerable fortune. And he was certainly aware of Édouard Manet’s notorious Olympia, which caused such a scandal when it debuted at the 1865 Paris Salon, and was in turn inspired by Goya’s nude Maja. Yet while Olympia’s direct stare challenges the viewer, and Ingres’ odalisques submit unprotestingly to our appreciation, Renoir’s bathers and nudes frolic cheerfully or smile welcomingly, inviting and responding to the male gaze.

Model:

‘It is the artist who makes the model’ (Renoir)

Much of the charm of Renoir’s nudes derives from the fact that the young women are pretty, in the bloom of health, and in high spirits. He was constantly in search of girls whose ‘skin took the light’. The model who posed for Femme nue couchée – and for perhaps two hundred other works from this period – was Fernande-Gabrielle Renard, known as Gabrielle, a distant cousin of Renoir’s wife Aline Charigot. It was Aline who, in August of 1894 invited Gabrielle to join the Renoir household at 13 Rue Girardon, Paris, to help care for the infant Jean. She remained with the family for the next 19 years.

Gabrielle was a practical and hard-working country girl. Jean Renoir later recalled that ‘at ten she could tell the year of any wine, catch trout with her hands without getting caught by the game warden, tend the cows, help bleed the pigs, gather greens for rabbits and collect manure dropped by the horses as they came in from the fields – a treasure which everyone coveted’ (quoted in J. Renoir, Renoir, My Father, New York, 1958, p. 264). High-spirited and resourceful, as well as deeply loyal to her family, Gabrielle soon became an indispensable helpmate, and even more so after Renoir purchased a house in the countryside in Aline’s native Essoyes. She was devoted to Jean, her chief responsibility, and became practically a second mother to him. Gabrielle’s warm presence features in many of Renoir’s most charming domestic scenes from this era, including Jean Renoir, Gabrielle et fillette.

Renoir began painting Gabrielle in the nude several years later, in 1899, one summer when the family had rented a house in Magagnosc, near Grasse. As Jean Renoir recalled: ‘It was in that house that Gabrielle began posing in the nude for the first time. La Boulangère [Marie Dupuis, a servant who joined the Renoir household in 1899] had a cold, and Renoir had tried in vain to get a model from Grasse. It was the rose gathering season for the perfume industry, and all the young people in the vicinity were employed. At the same time, it is possible that the prospect of appearing naked in front of a gentleman frightened many of the girls…My mother finally had the idea of getting Gabrielle as a substitute. She had just turned twenty and she was in the flower of youth. She was so accustomed to seeing her friends pose in the nude that she took the suggestion as a matter of course. She had already appeared in countless pictures, but always fully clothed and always with me’ (J. Renoir, op. cit., pp. 365-66). At ease and unselfconscious, as well as reliably available, Gabrielle offered Renoir an ongoing source of inspiration. And as the dealer Ambroise Vollard commented: ‘After [Renoir] had got a model “well-worked into his brushes”, it was a great annoyance for him to change’ (quoted in A. Vollard, Renoir, an Intimate Record, New York, 1925, p. 83).

Technique:

While Renoir’s nudes of the 1880s explore the linearity of Renaissance classicism, the 1890s witnessed a return to the painterliness of his earlier years, and in Femme nue couchée Gabrielle’s form is defined by a mix of energetic strokes and long, elegant brushmarks that follow her rounded contours. He looked more to Rubens and Titian than to the French Rococo inspiration of his early years, applying the paint in thin, layered veils of translucent colour. His palette relies on a range of creamy reds and pinks which are contrasted against the brown, green and chartreuse tones of the divan and cushions, while Gabrielle’s dark hair and eyes provide a counterpoint to the white drapery.

To execute Femme nue couchée, Renoir evidently placed his easel close to the edge of the cushioned divan on which Gabrielle reclines. There is minimal space between the viewer and the model, and, combined with the large scale of the work, this gives the sense that she is virtually life-sized. The ground beyond her is flattened, and the drapery covering the divan unadorned, presumably so as not to compete with the model herself. Gabrielle rests on her left side with her knees drawn up slightly to create a curving S-shape, her upper thighs partially draped (likely in deference to the public space of the Salon) and she wears a pink rose in her hair. This detail, which appears in a number of works from this period, may have been inspired by Delacroix’s great Les Femmes d’Alger, another Orientalist masterpiece in the Louvre that prompted Renoir to declare to Vollard: ‘There isn’t a finer picture in the world…How really Oriental those women are – the one who has a little rose in her hair for instance!’ Above all, this is a celebration of warmth and femininity; vibrant youth, and vigorous good health.

Salon:

Renoir submitted Femme nue couchée to the 1905 Salon d’Automne, along with eight other works. He had been honoured with a small retrospective exhibition at the previous year’s Salon, at which he showed 34 paintings. The 1905 Salon featured rooms devoted to Ingres and Manet, but the most talked about section was Salle V, where visitors gathered to view recent works by Matisse and his colleagues; their strident colours stirred up a frenzy of controversy and led critic Louis Vauxcelles to dub them Les Fauves, ‘the wild beasts’. Amid this mix of past and present was Renoir, one of the few surviving grand old men of the Impressionist movement, whose work continued to evolve and was now most notable for its joyous sensuality. His late works served as an inspiration to younger painters including Matisse and Picasso.

Femme nue couchée was favourably received by critics. The Nabis painter Maurice Denis wrote: ‘Renoir, who is no longer remotely an Impressionist, triumphs here with his astonishing latest manner, with robust, abundant nudes like the Raphaels of the Fire in the Borgo and the Farnesina: note how his knowledge of tonal gradations and modelling has in no way compromised his freshness and simplicity’. The painting’s success prompted Renoir to produce two further related works before he sold the picture to his dealer Paul Durand-Ruel in 1907. Both of these are of comparable size. Femme nue couchée (Gabrielle), completed in 1906, gives a more diaphanous quality to the background drapery. Nue sue les cousins (Grand Nu) was painted in 1907 and features a red-haired model, although her recumbent pose, her left hand supporting her head on the floral cushion, remains the same. He also engraved the composition.

Provenance:

Femme nue couchée was first owned by the great French dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who began selling Renoir’s work in 1881 (fig. 21). The fact that it was not sold immediately after its execution in 1903 underscores Renoir’s own approval of the piece; very likely he already intended to paint further versions. It later belonged to the German financier and collector Maximilian von Goldschmidt-Rothschild, who was, along with his brother Adolphe Goldschmidt, the co-inheritor of the Goldschmidt family bank (fig. 22). He appended the Rothschild name following the death of his father-in-law, Wilhelm Carl von Rothschild, the last of the male Frankfurt Rothschilds, and was created Baron de Goldschmidt-Rothschild by Emperor William I. Maximilian and his wife Minna adopted the Rothschild name, and the Emperor William I gave him the title Baron de Goldschmidt-Rothschild. At one point Maximilian von Goldschmidt-Rothschild was believed to be the richest person in the German Empire. Among the works in his impressive collection were modern masterpieces by Manet and Van Gogh (figs 23-24).

Femme nue couchée next belonged to the Belgian Jos (born Joseph) Hessel, an art dealer, collector and critic based in Paris. He represented, among others, his friend the painter Édouard Vuillard. Hessel sold the work back to Durand-Ruel’s New York Gallery in 1926, after which it was owned by Knoedler & Co. More recently, in 2010 Femme nue couchée was acquired by the current owner from the Estate of Raymond and Miriam Klein, prominent Philadelphia-based collectors and philanthropists.

Conclusion:

‘Like figures painted by the aged Titian or Rubens, these nudes capture a powerful sexuality, a metaphor of life itself in the contrast between the artist’s physical deterioration and his figures’ increased sensuality. He compensated for his own sickness, emaciation, and paralysis by brilliantly expressing health, corpulence and vitality. His powerfully optimistic nudes express his resilient defiance’ (B.E. White, op. cit., p. 229).

Given the strong associations between Renoir and the female nude, it is perhaps surprising, as Sir Kenneth Clark observed, that he was relatively late in taking it up as a subject: ‘Everyone who writes about Renoir refers to his adoration of the female body, and quotes one of his sayings to the effect that without it he would scarcely have become a painter. The reader must therefore be reminded that until his fortieth year his pictures of the nude are few and far between’ (K. Clark, The Nude: A Study of Ideal Art, London, 1956, p. 154). His interest and enthusiasm for the idealised nude were renewed by his 1881 travels to Italy, during which he admired Raphael’s frescoes and classical sculpture. The linear monumentality of the early 1880s ultimately gave way to a freer, more painterly treatment of the subject, exemplified by Femme nue couchée. This richly coloured, luminous depiction of a favourite model reflects Renoir’s legacy as the premier Impressionist painter of the female form.