Many great artists have chosen London as their subject, and captured views of it in various media. Our selection of these views demonstrates not only how London has changed in 500 years, but also how artists’ attitudes towards view painting have evolved in that time.

Wenceslaus Hollar, Long View of London from Bankside (one sheet), 1647, Royal Collection Trust, London

The first artwork on our list is neither a painting nor a drawing, but rather an etching produced for publication. Hollar, the artist responsible, was born in Prague in 1607, and established himself in England as the foremost graphic artist of his day. He was known primarily for his architectural depictions and topographical works (some of which border on the cartographic), and his greatest achievement is perhaps this panorama of London. Not illustrated here in full due to its format, the entire panorama measures 47.8 x 237 cm and is comprised of several printed sheets. This work is notable for two principal reasons: First, it is hugely innovative in that it is a panorama taken from a single viewpoint (the spire of what is now Southwark Cathedral), and second, it was the most complete and accurate artistic depiction of London to that point. It is of particular interest as it shows London less that 20 years before it was ravaged by the Great Fire in 1666. It is also significant as it centres its view on St Paul’s Cathedral, the City of London then being the centre of the capital, with Whitehall being relegated to a small addition at the bottom left corner.

Canaletto, Westminster Bridge with the Lord Mayor’s Procession on the Thames, 1747, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven

The first artwork on our list is neither a painting nor a drawing, but rather an etching produced for publication. Hollar, the artist responsible, was born in Prague in 1607, and established himself in England as the foremost graphic artist of his day. He was known primarily for his architectural depictions and topographical works (some of which border on the cartographic), and his greatest achievement is perhaps this panorama of London. Not illustrated here in full due to its format, the entire panorama measures 47.8 x 237 cm and is comprised of several printed sheets. This work is notable for two principal reasons: First, it is hugely innovative in that it is a panorama taken from a single viewpoint (the spire of what is now Southwark Catherdral), and second, it was the most complete and accurate artistic depiction of London to that point. It is of particular interest as it shows London less that 20 years before it was ravaged by the Great Fire in 1666. It is also significant as it centres its view on St Paul’s catheral, the City of London then being the centre of the capital, with Whitehall being relegated to a small addition at the bottom left corner.

J.M.W. Turner R.A., The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons, 16th October 1834, 1834-35, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Painting almost exactly the same view as Canaletto, almost 100 years later, J.M.W. Turner gives us Westminster Bridge in rather more troubled times, namely the burning of the Houses of Parliament in 1834. This terrible fire razed the old parliament buildings and made way for the high gothic revival Palace of Westminster that stands today. As a painter of the early 19th century and, as such, deeply predisposed to the sublime and romantic aspects of the landscape, it is only fitting that Turner chose as his subject a moment of destruction and terror. By doing this, the artist did away with the more topographical and orderly conventions of Canaletto, and indeed the previous century, focussing his efforts on evoking the drama of the event through dazzling atmospheric effects and brilliant colouring.

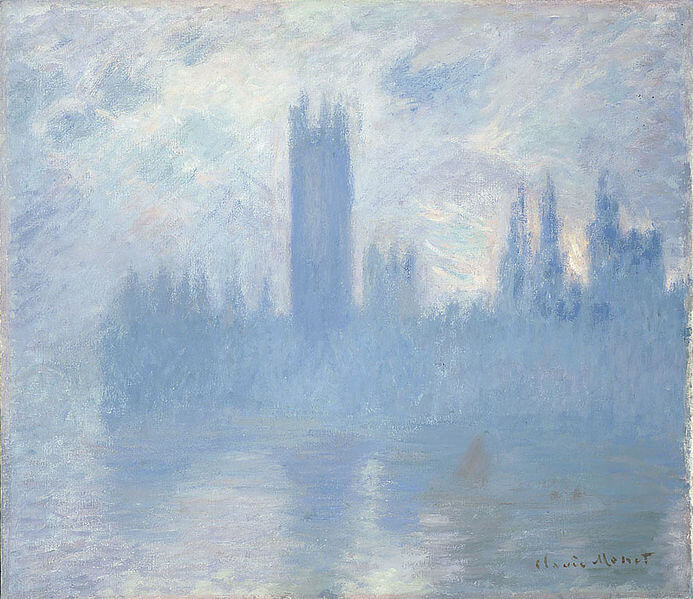

Claude Monet, House of Parliament, London, 1900-01, Art Institute of Chicago

Painted on almost exactly the same spot as Turner’s 1834 picture, Monet’s composition subjects the view of Pugin and Barry’s Palace of Westminster to a full Impressionist treatment. In many ways, Monet has picked up where Turner left off, although in this picture (and the many like it) he was not necessarily interested in recording an event, or even a view, but rather the impression of the view as dictated by the atmospheric conditions. Monet was almost certainly inspired by James Abbot McNeill Whistler, whose nocturnes of the Thames from the 1870s utilised the same semi-abstracted blues that Monet relied upon here.

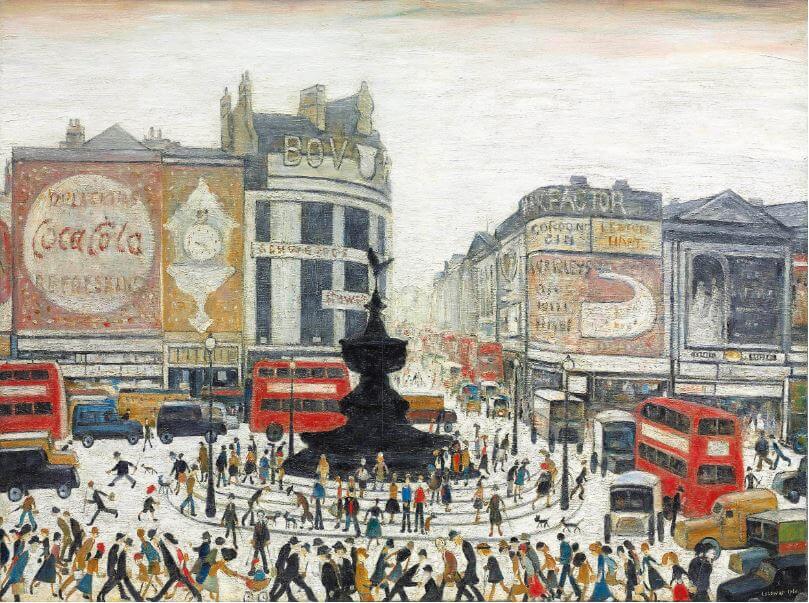

Laurence Stephen Lowry R.A., Piccadilly Circus, London, 1960, Private Collection

A far cry from the calm of Monet’s dusky river scene, we now find ourselves in the bustle of Piccadilly Circus, the hub of the West End, at the start of the 1960s. Although Lowry could never properly be described as a London artist (he is far too synonymous with the North-West for that), this picture is deeply evocative of the capital in the mid-twentieth century. The iconic red London buses are as ubiquitous a presence as the bowler-hatted businessmen and the youths congregating at the statue of Eros. Set against the colourful advertising of Piccadilly Circus, Lowry’s ‘matchstick men’ are here imbued with a kind of fun and vitality not always seen in some of his bleaker industrial scenes. The excitement of this image is only heightened by our knowledge that 60’s swinging London was only just around the corner.

Frank Auerbach, Mornington Crescent – Summer Morning, 2004, Tate Gallery, London

If Monet and Turner painted landscapes with elements of abstraction, then Auerbach here gives us what is, at first impression, an abstract painting with landscape elements. Once our eyes begin to read the colours and the shapes at play, we can understand the picture to depict buildings to the left, a street running down the centre, a block of flats to the right and some innocuous street furniture in the form of lampposts and traffic lights. Auerbach, known for his abstracted figurative pictures, worked up in heavily layered paint, is also a prolific painter of his adopted home streets of north London. Auerbach first set up studio in Camden in the early 1950s and has, ever since, looked to its streets as a reflection of his inner state, explaining: ‘it’s never just topography, it is never just recording the landscape. It always has to do with some sort of feeling about my life’. This picture, thinly painted by Auerbach’s standards, evokes the city waking up, and the dawn light hitting the buildings, but unlike in Monet’s view, here the hard, spikiness of the 20th century metropolis is very much brought to the fore.