It won’t have escaped anyone’s notice (no matter how much we might wish it) that 2024 is a year of political upheaval, with important elections held around the world. In March, elections in Russia saw Vladimir Putin elected for a fifth term, with an overwhelming majority that surprised no one. In France, two rounds of elections on 30 June and 7 July might see President Macron displaced in favour of the right-wing Rassemblement National. In the United States, the 60th Presidential Election is set to take place on 5 November. And in the UK today, citizens head to the polls for the General Election. Whatever your political affiliations, however, we hope you enjoy our selection of 10 of our favourite political artworks (from a field of many highly qualified candidates).

Sir Peter Paul Rubens, The Apotheosis of James I, c. 1632-34, Banqueting House, Whitehall, London

Rubens, then the leading artist in Northern Europe, was too busy to take on the commission for the ceiling’s of James I’s new Inigo-Jones-designed Banqueting House when he was first approached in 1621. It was only after James’s death in 1625, when Rubens was in England for eight months at the end of the decade, that he was formally granted the project by the new king Charles I. The nine-canvas cycle, which celebrated James’s peaceful reign, the unification of the crowns of England and Scotland, and then glory of the House of Stuart, was completed in Antwerp in the artist’s studio and had been installed by March 1636. In 1649, Charles I passed beneath the magnificent Rubens ceiling on his way to his execution.

Velázquez, The Surrender of Breda, 1634-35, Museo del Prado, Madrid

This monumental painting depicts the exchange of keys of the city of Breda in the Netherlands, given by the conquered Dutch leader Justinus van Nassau to the victorious Genoese general Ambrogio Spinola after the Siege of Breda during the Eighty Years War. It was commissioned from the artist by Philip IV of Spain for his Palace of Buen Retiro in Madrid, as a means of glorifying Spanish military success. Velázquez has depicted both sides with dignity, and his recollection of Spinola’s character is believed to be accurate as the two had travelled to Italy together and were well acquainted. The colouring is inspired by the painterly hues of the Venetian art to which Velázquez was exposed during that trip and in the Spanish royal collection.

William Hogarth, The Humours of an election, 1754-55, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

This four-painting series by leading satirist William Hogarth – who would undoubtedly find himself rich with inspiration in today’s political environment – explores the rampant election corruption in 18th century Britain. Like other popular series such as Marriage a la Mode and A Rake’s Progress, The Humours of an election was a project conceived as preparatory to a series of engravings sold as sets to subscribers. Hogarth’s four scenes depict the courting of the electorate by candidates to win support; the bribery of the electors; the skulduggery of the election day and the celebration of the victors. Filled with humour and symbolism, the paintings – which once belonged to the actor David Garrick – constitute a masterpiece of political satire. Other leading political satirists of the 18th Century include Thomas Rowlandson and James Gillray.

Francisco de Goya, The Third of May, 1808, Museo del Prado, Madrid

Goya’s painting, which commemorates Spanish resistance to Napoleon during the Peninsular War, highlights the bravery of the Spanish people and the tragic fate of many who were executed by French forces. In Goya’s composition, the French firing squad appears from behind, the soldiers’ faces hidden as they stand shoulder to shoulder facing their victims. The Spanish rebels stand with their backs against a stone wall, illuminated by a lantern that separates the two groups. On the ground are the dead; the viewer’s attention is drawn to the central figure, a labourer in a white shirt, his arms flung wide in surrender while other members of the group shield their eyes in terror. According to Kenneth Clark, this is ‘the first great picture which can be called revolutionary in every sense of the word, in style, in subject, and in intention.’

Eugène Delacroix, Liberty leading the people, 1830, Musée du Louvre, Paris

This, the iconic image of the French Romantic era, was painted to commemorate the 1830 July Revolution that saw the Bourbon monarch Charles X deposed and replaced by his cousin Louis Philippe, Duc d’Orléans. The Goddess of Liberty, personified by a woman waving the tricolor while carrying a bayonetted musket, leads a group of revolutionaries over a barricade and a pile of the bodies of the fallen. By the time Delacroix painted the work, about which he wrote to his brother ‘if I haven’t fought for my country at least I’ll paint for her’, he was acknowledged as the leading Academic painter in France. This work was exhibited at the 1831 Salon, where it was initially requested for purchase by the French Government but later returned to the artist as too inflammatory.

J.M.W. Turner, The Slave Ship, 1840, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

Turner’s ‘The Slave Ship’ must count among the most moving artworks painted in support of the abolitionist cause. It seems probable that Turner was inspired by a horrific account of the Zong massacre in The History and Abolition of the Slave Trade by Thomas Clarkson (2nd ed. Published 1839). In 1781, the crew of the slave ship Zong, running short of drinking water, murdered over 130 enslaved Africans by throwing them overboard in order to claim for the loss on insurance. The tragedy fuelled the abolitionist movement, and the exhibition of The Slave Ship at the Royal Academy the year it was painted coincided with two significant anti-slavery conventions. Turner’s painting features an ominous, blood-red sky against which is silhouetted a ship with furled sails. In the foreground, limbs emerge from the turbulent waters, still chained and beset by a frenzy of fish and gulls.

Emanuel Leutze, Washington crossing the Delaware, 1851, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Ask anyone – even an art historian – who Emanuel Leutze was, and you may well get a quizzical look. But mention his most famous painting and the story is very different. Leutze, a 19th Century German-American artist associated with the Düsseldorf school, initially painted Washington Crossing the Delaware to inspire liberal reformers in Europe with the American Revolutionary model. The painting actually existed in three versions: the first, formerly in the Kunsthalle Bremen, was destroyed in a World War II bombing; the second, largest version is in New York’s Metropolitan Museum, and a third, smaller version sold at auction in 2022 for $43 million. The painting depicts General George Washington’s campaign against the Hessians in Trenton New Jersey on Christmas Day 1776. Although inspiring, the painting is not historically accurate: in fact, Washington’s army crossed the river at night to avoid detection.

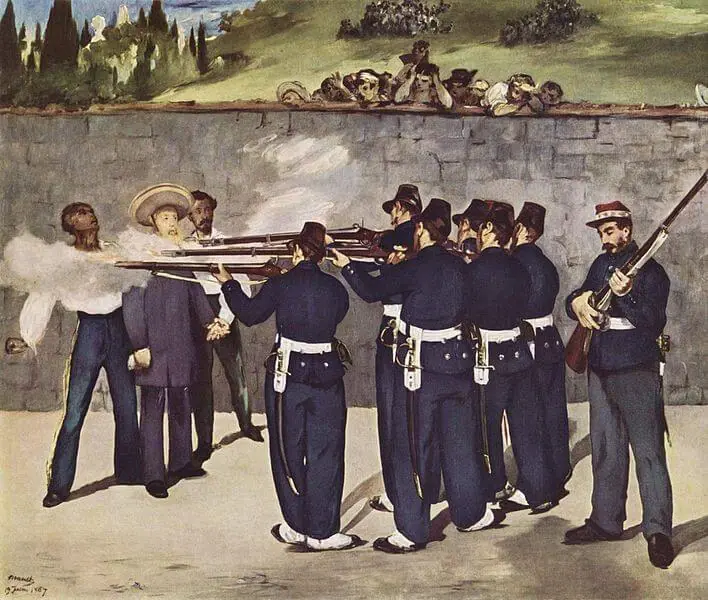

Edouard Manet, Execution of the Emperor Maximilian, 1868-69, Kunsthalle Mannheim, Mannheim

This composition was directly inspired by Goya’s The third of May, and exists in three large paintings, a smaller oil sketch and a lithograph of the subject. Having been put forward by Napoleon III to become Emperor of Mexico following the French occupation, Maximilian arrived in May of 1864 but was left unsupported when French forces withdrew in 1866. He was captured by those loyal to the deposed president Benito Juárez, tried, condemned, and executed on 19 June 1867. Although Manet was a republican in his politics, and disapproved of French intervention in Mexico, he was moved to depict the event after reading about it in the papers. Due to its political nature, the painting was not accepted at the Salon, nor was Manet’s lithograph permitted to be sold, sparking a debate on censorship.

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937, Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid

Picasso’s Guernica is probably the artist’s best-known work as well as his most moving. Having wrestled, without success, in search of a theme for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair, Picasso was struck by inspiration following the tragic 26 April bombing of the Basque town of Guernica by Francisco Franco’s Nationalist army. Picasso’s creative process was documented in photographs by Dora Maar, his muse at the time. Motifs include the Spanish bull and a screaming, wounded horse, while a dead soldier is stretched across the foreground and a wailing woman at left clutches the body of a dead child. Guernica was sent to America to raise funds for the Republican cause, and Picasso stipulated that it was not to return to Spain until the nation was liberated from Franco. It was ultimately returned to Spain, reluctantly, by New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1981, eight years after the artist’s death.

Frida Kahlo, Self-portrait dedicated to Leon Trotsky, 1937, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C.

The Mexican artist Frida Kahlo and her husband, muralist Diego Rivera, had been members of the Mexican Communist party when a dispute with leadership saw Rivera expelled in 1929. Kahlo left the party in solidarity with her husband, and they shifted their allegiances from Stalin to the exiled Leon Trotsky, eventually persuading the Mexican president to grant Trotsky and his wife asylum. When the couple came to stay with Kahlo and Rivera at their home, La Casa Azul, in 1937, Kahlo and Trotsky embarked on an affair. This self-portrait, painted as a gift for Trotsky on his 58th birthday, bears the dedication ‘To Leon Trotsky, with all my love, I dedicate this painting on the 7th of November 1937. Frida Kahlo in San Ángel, Mexico.’