El Greco (1541 – 1614)

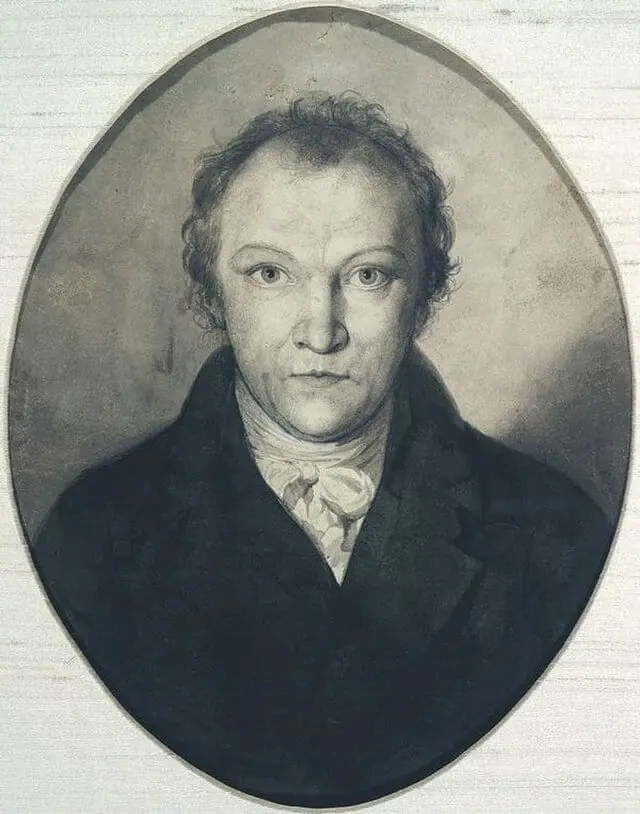

El Greco, Presumed self-portrait, or portrait of an anonymous man, c. 1595-1600, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

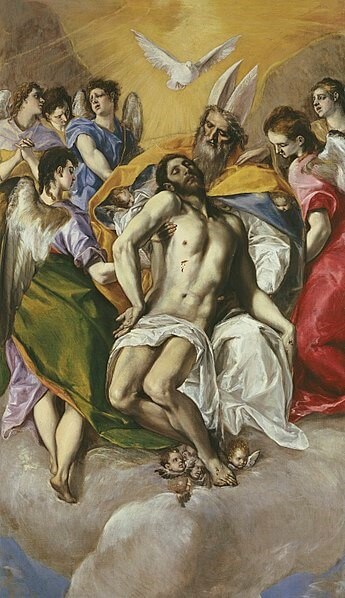

Dominikos Theotokopoulos was born on the island of Crete in 1541. This Greek island was, in the 16th century, host to both Venetian (Crete was part of the Republic of Venice) and eastern Byzantine artistic influences, both of which underpinned the Cretan school to which Theotokopoulos belonged. Aged twenty-six, the painter relocated to Venice, and, having become a master in the post-Byzantine tradition, he learned to incorporate the styles of great Venetian painters Tintoretto and Titian. Having served his apprenticeship on the Italian peninsula, he moved to Spain, first to Madrid and then Toledo where he finally settled in 1577. Here, by combining Byzantine and Mannerist conventions with Venetian colouring, he pioneered his mature style so characterised by the elongation of human forms, a fantastical colour palette and ambiguous spatial arrangements. His best works from this period are monumental religious pictures, usually intended as altarpieces. It was also at this point that he received his nickname ‘El Greco’ – ‘The Greek’. During this time, he sought the patronage of Philip II of Spain, who was in the process of decorating his palace of El Escorial. He was initially commissioned by Philip II to paint an altarpiece for the chapel there, but, on its completion, Philip disliked the result and had the work moved to the chapter-house. This slight marked the end of El Greco’s aspirations to royal patronage and forced him to focus his efforts on Toledo-based commissions. He would die in the city in 1614 aged 72.

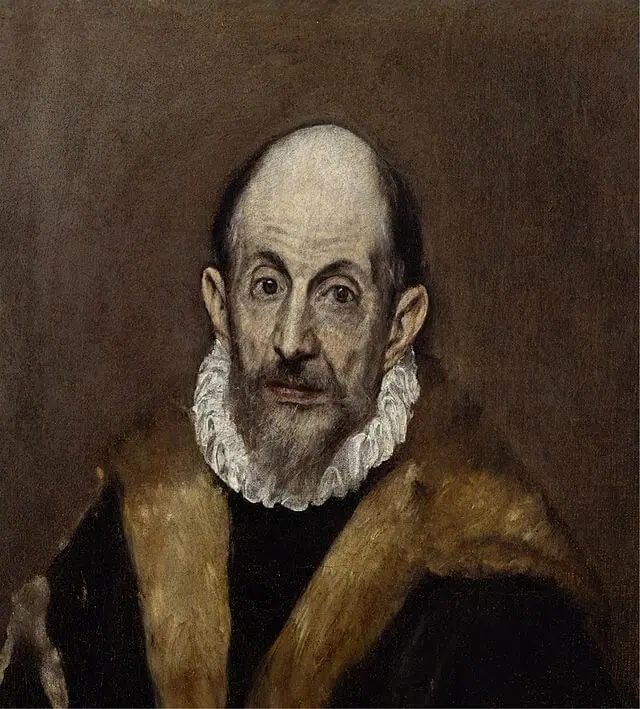

El Greco, The Holy Trinity, 1577-79, Museo del Prado, Madrid

Although El Greco’s career was by no means a failure, he was certainly not held in the regard with which we treat him today. His style of painting defied characterisation and he left behind him no school of followers. In the decades after his death, he was regarded as an eccentric one-off, whose pictures’ strangeness was seen as evidence of a defective – not genius – artist. It would take until the late 18th century for his work to be re-evaluated in the light of Romanticism. He was seen, especially by the French author Théophile Gautier, as a radical painter, labouring entirely under his own visionary imagination. By the 20th Century, he had been rehabilitated both through literature and exhibitions, and proved to be a major influence upon Modernist movements such as Cubism and on Pablo Picasso specifically. El Greco worked ‘with complete indifference to what effect the right expression might have on the public’, said the English critic Roger Fry. He was ‘an old master who is not merely modern, but actually appears a good many steps ahead of us, turning back to show us the way’.

Johannes Vermeer (1632 – 1675)

Johannes Vermeer, The Procuress (detailed of supposed self-portrait), 1656, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden

Vermeer is known today as one of the very greatest products of the Dutch Golden age. The fact that he produced so few paintings (only 35 are firmly accepted today) means that his work is extremely rare and thus considerably more valuable than pictures by many of his contemporaries. His oeuvre is almost entirely characterised by interior genre scenes capturing the rituals of daily life in 17th Century Delft, from high society to low. These pictures were almost all painted in a few rooms in his house, which are recognisable across his works. In addition to such scenes, he painted one religious picture and two views of his native Delft. Vermeer’s early career remains obscure: it is not known if he was apprenticed to a master, or even if he had any formal training as a painter.

He worked slowly and methodically – this is very much evident in the highly-finished and precise nature of his works – and perhaps only completed three pictures per year. His most significant patrons were the husband and wife Pieter van Ruijven and Maria de Knuijt, who owned many of his pictures. Vermeer appears not to have had any considerable fame outside of Delft and made most of his modest living as an art dealer rather than as a painter. He seems not to have been highly successful in his business ventures and, in 1675, he died, leaving his wife in debt and with many works remaining in his studio, unsold.

Johannes Vermeer, The Milkmaid, c.1600, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

There was little clue as to Vermeer’s later renown in the painter’s lifetime or, for that matter, in the following two centuries. It would take until the 1860s when the writer Théophile Thoré-Bürger ‘rediscovered’ Vermeer by writing and publishing a catalogue raisonné of his works. Since then, his oeuvre of accepted works has been whittled down by almost half and every accepted picture is in a major public collection (with the notable exception of The Concert, which was stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 1990). No fully accepted work by the artist has appeared at auction for 100 years – Sotheby’s sold A young woman seated at the virginals for over £13 million in 2004, but the painting still lingers in the ‘attributed to’ category. Barring a major rediscovery, it is highly unlikely that a work by the artist will appear for public sale again. That said, if it were to happen, the price would surely be in the hundreds of millions.

William Blake (1757 – 1827)

Whilst William Blake’s work was not completely unknown during his lifetime, it was, however largely ignored and dismissed as the feverish production of a madman. Blake was many things: a poet, artist, illustrator, visionary, and religious mystic. He was born, lived his whole life (apart from three years in Sussex) and died in London and never left England. From an early age he claimed to be see visions of God, Christ and angels, and over the course of his life he would develop his own mystic version of Christianity – one that rejected the organised church and all the repressions and self-denials that brought. He instead committed to a spiritual relationship with Christ and the God of the New Testament.

Blake made his money as an engraver and illustrator. He trained as a printer with the engraver James Basire, who educated him in the art of line engraving. From a young age he was engraving copies after Renaissance paintings and making prints from the sculpture and architecture of Westminster Abbey. He later enrolled in the Royal Academy schools where he rebelled against the apparent hypocrisy of President Sir Joshua Reynolds’ lofty and classicising artistic doctrine, which, given that he worked primarily as a portraitist, Reynolds often failed to adhere to himself. Instead, he took inspiration from the irascible Irish painter James Barry, who single-mindedly pursued a career as a painter of idiosyncratic historical and mythological scenes, most of which met with complete critical ambivalence.

Like Barry, Blake made no concessions when it came to his own artistic, political or religious beliefs. He was regarded variously as a dangerous radical for his sympathies with revolutionary America and France and simply as a madman for his obscure religious beliefs.

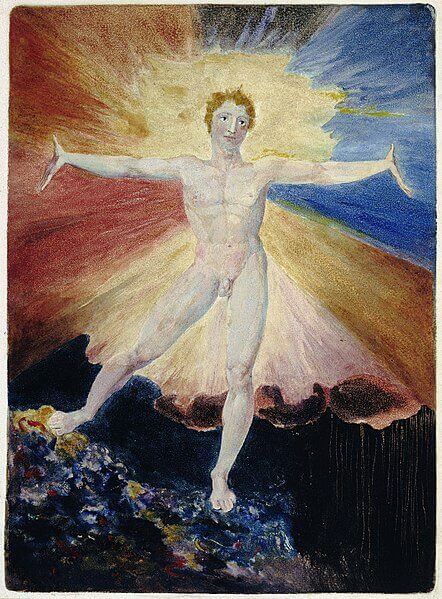

Blake was as much a poet as a visual artist and some of his most notable works are ‘illuminated’ or illustrated collections of his poetry, such as Songs of Innocence and Experience (1789). He also produced prophetic writings which, again, he illustrated. He was more successful as an illustrator of other people’s writings, however, and he provided images for Milton’s Paradise Lost, Dante’s Inferno and The Book of Job from the Old Testament.

William Blake, Albion Rose, from A Large Book of Designs, 1793, The British Museum, London

Blake, however, was a complete commercial failure when it came to selling his own productions. He organised exhibitions of his work which failed to sell a single picture and, by the time of his death, he had only sold just 30 copies of the now canonical Songs of Innocence and Experience. Most of the works he did sell were to friends, who bought them mainly, it seems, out of sympathy.

Although he died mostly unknown and practically destitute, Blake’s critical rehabilitation did not take long. He left behind him a small group of followers called the Shoreham Ancients, of which Samuel Palmer was the most famous member. He was, however, widely rediscovered by the Pre-Raphaelites, especially Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and a biography by Alexander Gilchrist was published in 1860. His words were set to music in 1916 in the Hymn ‘Jerusalem’ and his visionary drawings and free-love views were highly influential in 1960s counter-culture.

Today, his prints and drawings are hugely valued, and many of them are in public collections. His auction record was set in 2004, with a watercolour selling for $3,928,000.

Vincent Van Gogh (1853 – 1890)

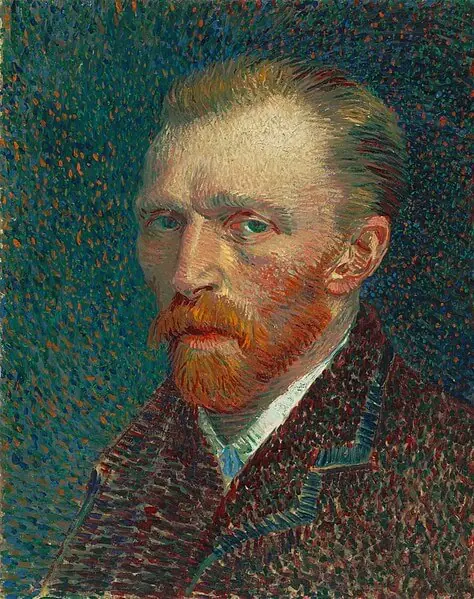

Vincent Van Gogh, Self Portrait, 1887, Art Institute of Chicago

Of all the painters whose enormous fame was found only after their deaths, Van Gogh is surely the best known. His work is amongst the most recognisable, popular and expensive art in the Western tradition. Born in Zundert, in the Netherlands, Van Gogh’s first began a career as an art dealer at the firm Goupil & Cie. Had reasonable success there before being dismissed in 1876. He spent the next few years in a string of itinerant positions, working variously as a teacher, bookseller and Christian missionary. He seems to have been generally dissatisfied and showed signs of the mental health issues that would so famously figure in the final years of his life. Van Gogh came to art only in the last decade of his life. His early works depicted rural peasants, with a dark, earthy colouring that characterised this ‘Potato Eater’ period, so named after his major work of 1885. Van Gogh would move to Paris in 1886, where he met emerging Impressionist painters Paul Signac, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Georges Seurat, and, through them, introduced the bright colour for which he is so well-known into his work. He then relocated to Arles, a sun-drenched town in the South of France. It was here that his mature style began to form, his colouring became more saturated and his brushwork more confident. Paul Gauguin visited and, in a moment of mental crisis, Van Gogh cut off part of his own ear – he was later hospitalised in Arles. His depression worsening and in a state of mental delirium, he continued to work compulsively. The majority of his oeuvre of over 2,000 pictures dates from the last two years of his life, a life cut short by suicide during a chronic relapse in 1890.

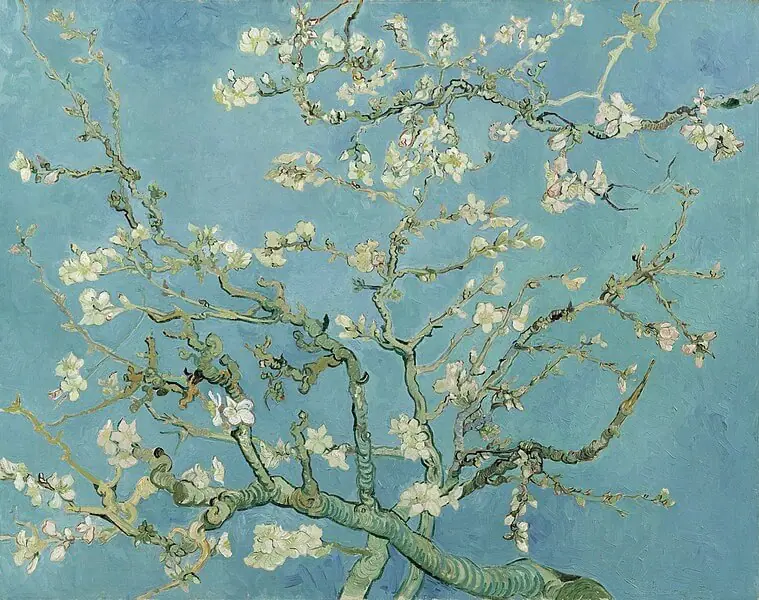

Vincent Van Gogh, Almond Blossom, 1890, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Van Gogh had only managed to sell one painting during his lifetime, but, tragically, his work was starting to gain some critical traction in the months before his death. He was the subject of retrospective exhibitions in Brussels and Paris in 1891 and, by the early 20th Century, his work was not only well-known, but proving influential to a new generation of Expressionist artists, especially in Germany. He now has a large museum in Amsterdam entirely dedicated to him and his pictures are amongst the most expensive ever sold, with his auction record standing at a remarkable $117,180,000.