The Lascaux Cave Paintings, Palaeolithic period, Lascaux, France

Thought to be at least 20,000 years old, these extensive cave paintings are among the world’s best-preserved examples of Palaeolithic art. The paintings primarily depict animals which were once native to the south-west region of France including cattle, birds and felines as well as human figures. Perhaps the most famous image is of four black bulls which demonstrate not only the artist’s (or artists’) ability to depict movement but also an early understanding of perspective. Since the early 2000s, the caves have featured electric light and air conditioning, which some say – through the increased light exposure and changes in humidity – have caused more damage than good, and public access is now being carefully managed. Fortunately, a new International Centre for Cave Art, located at the foot of Lascaux hill, welcomes visitors to explore its complete replica of the original cave and its paintings.

Giotto di Bondone, called Giotto, The Lamentation, 1305-06, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua Italy

The frescoes of the Scrovegni chapel mark a distinct leap in the development of Western art. Commissioned by Enrico Scrovegni, a wealthy Paduan banker and money-lender looking to repent for his usurious sins, Giotto and his team of 40 assistants worked to cover the interior walls of the chapel – 700 square metres in total – with a series of four separate fresco cycles. These depict the Life of the Virgin and the Life of Christ (which each run along the lateral walls in three tiers), the Cardinal Virtues and Vices, and The Last Judgement, above all of which spans a ceiling of midnight blue decorated with stars. This particular work, The Lamentation, features as one of the 23 frescoes that show the Life of Christ and is a fine example of Giotto’s skilful storytelling. Not only is the emotion, sadness and distress on the figures’ faces depicted with such realism, but also the image is imbued with such movement – the flight of the putti as they dart down from heaven and the flow of the figures’ drapery as they bow and kneel before Christ – which forms the perfect contrast to His still and silent body.

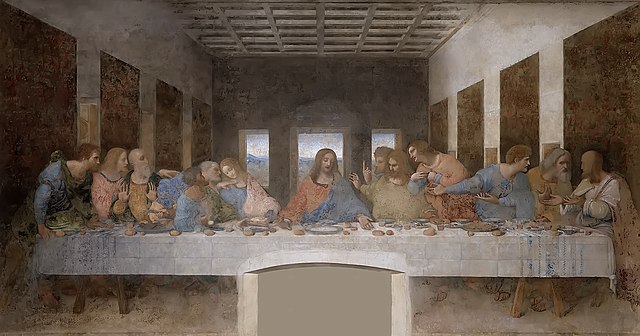

Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper, c. 1495-98, Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan, Italy

From one wall painting to another, Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper – like Giotto’s work – epitomises the very best of the Italian Renaissance. Not only this but Leonardo’s fresco also speaks of his innovative, experimental and curious character which made him the ‘Renaissance man’. Rather than using the more traditional fresco method of painting directly into wet plaster, he used a dry technique, incorporating the use of oils. Whilst this allowed for a smoother finish to his work, he somewhat sacrificed the strength and structural integrity that buon fresco (wet plaster fresco painting) provides, whereby colour pigments become part of the wall as the plaster dries. However, despite harmful attempts at restoration in the 18th century and the ravages of the Second World War – during which the church and refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie were badly bombed – Leonardo’s painting survives and now benefits from controlled environmental conditions intended to preserve it for years to come. Described by Giorgio Vasari as ‘a beautiful and marvellous thing’, this is surely one artwork not to be missed.

Tiziano Vecellio, called Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1520-23, The National Gallery, London, England

One of three bacchanals (or hedonistic scenes) commissioned by Alfonso d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne depicts the moment that Bacchus, god of wine, falls for the abandoned princess Ariadne and leaps forth from his chariot, drawn by cheetahs, to meet her. Although scared of Bacchus at first, Ariadne is won over when he promises her the stars and the two are later wed. The constellation of stars – the ‘Corona Borealis’ – in the top left-hand corner is Titian’s reference to Ariadne’s wedding crown, which Bacchus is said to have thrown skyward in celebration of their union. Although the exact place that this painting would have occupied in the Duke of Ferrara’s palace is unknown, there can be no doubt that – alongside its two companion paintings Feast of the Gods and Bacchanal with Vulcan by Giovanni Bellini and Dosso Dossi respectively – his interiors would have been something to be envied.

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, called Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam, c. 1512, The Sistine Chapel, Vatican City

Perhaps the most recognisable of Michelangelo’s frescoes for the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, The Creation of Adam illustrates the Genesis phrase ‘God created man in his own image’. Lying on the ground, Adam reaches out his left hand towards God who has appeared from Heaven with a band of angels. With God reaching His hand out to Adam in return, Michelangelo has captured the moment just before their fingers meet. This is an image filled with suspense and tension, with its distinct contrast between the whirling motion of God’s cloaked arrival and the stillness of the two figures’ gestures. This fresco alone took sixteen days to complete, a testament to Michelangelo’s creative efforts and to the completion of such an enormous artistic undertaking.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith beheading Holofernes, c. 1620, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy

Another religious work, Gentileschi’s Judith beheading Holofernes depicts the drunken army general, Holofernes – who has fallen asleep after dinner – being murdered by Judith, a young Jew from Bethulia. The bible describes how Judith’s heroism and determination to outdo Holofernes saves the people of Israel from a military siege. Completed during Artemisia Gentileschi’s return from Florence to Rome – of which she was a native – this work demonstrates the influence of the Caravaggio upon her artistic practice, which is most noticeable in the sharp contrasts of light and dark, and the deep shadows this creates. Indeed, Judith and her accomplice are partially lit, their limbs and faces bright but their bodies barely distinguishable, which only serves to intensify the drama of this clandestine act.

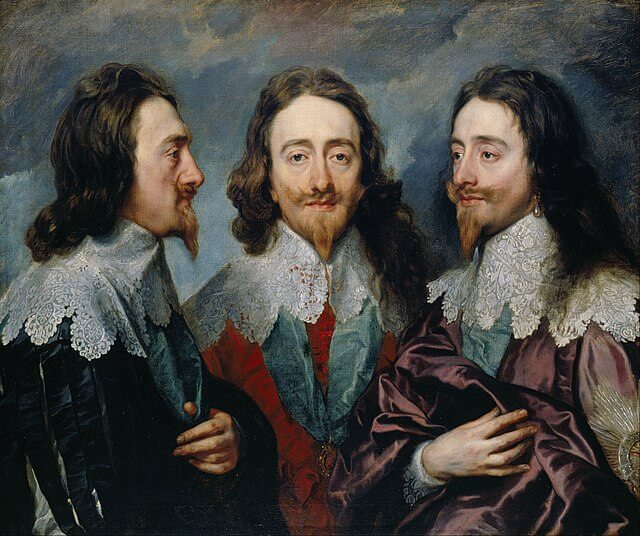

Sir Anthony Van Dyck, Charles I (1600 – 1649), 1635-36, Windsor Castle, Windsor, England

Painted by a well-remembered painter of the English Royal court, this triple portrait of Charles I by Sir Anthony Van Dyck was originally intended as a visual aid to the Italian sculptor Lorenzo Bernini. Commissioned in 1636 to produce a marble bust of King Charles I as a gift to his wife, Henrietta Maria, Bernini was sent Van Dyck’s painting to work from. This he duly did, and his completed sculpture was present to the King and Queen in July the following year (although it was later destroyed by the fire at Whitehall Palace in 1698). What remains of this creative collaboration, however, is this sensitive and relatively restrained – at least for Van Dyck – portrait of the King. No doubt inspired by Lorenzo Lotto’s Portrait of a Man in Three Positions, which belonged to Charles I at the time, Van Dyck has captured the King’s countenance, costume and character from almost every angle. Although very much a study – as was its intended purpose – this work is a fine example of the artist’s great skill and ability to render figures with undeniable realism.

Thomas Gainsborough R.A., The Blue Boy, c. 1770, Huntington Art Gallery, California, USA

Thomas Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy is without question an iconic painting. Formally titled A Portrait of a Young Gentleman when it first appeared in public at the Royal Academy in 1770 (only acquiring its nickname by 1798), this is Gainsborough’s take on the British ‘grand manner portrait’ tradition. Captured by the brilliance of its colours and the child-like yet simultaneously serious expression on the young boy’s face, Henry and Arabella Huntington famously purchased the work through Sir Joseph Duveen in 1921. Before it travelled to their home in California, however, The Blue Boy hung at The National Gallery, London, for three weeks where visitors could bid it farewell. One hundred years since that date, in 2022, it returned to London once again for a short commemorative exhibition and was displayed alongside other celebrated artworks.

John Constable R.A., The Hay Wain, 1821, The National Gallery, London, England

Offering a view of Flatford Mill and its pond– a view synonymous with Constable and early 19th century England – The Hay Wain was one of three large Suffolk landscapes that the artist showed at the Royal Academy between 1819 and 1825. It depicts a wagon (or hay wain) crossing a river ford – from which Flatford takes its name – towards a field where haymakers are at work with their scythes and pitchforks; it is in every sense an idyllic country scene. Although it is an image of the Suffolk countryside, the painting itself was in fact executed in Constable’s London studio. He was, of course, familiar with the landscape around Flatford having himself been born only a mile or so away at East Bergholt and we know that he made many pencil and oil sketches of the millpond and the surrounding buildings over many years, which no doubt contributed to the creation of his larger compositions. His return to this same location as a subject for his art – culminating in the production of these highly-detailed paintings – have made Flatford a landscape that is recognised and visited by people the world over.

Katsushika Hokusai, Under the Wave off Kanagawa, c. 1830-32, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

One of a large number of woodblock prints, this work by Katsushika Hokusai, which is known more commonly as ‘The Great Wave’, is widely considered one of the most recognisable and enduring of Non-Western images. It depicts a stormy sea, across which three small boats are tossed and thrown. One great wave – from which the work takes its nickname – dominates the left-hand side of the image and renders Mount Fuji, depicted in the background, minute in comparison. The interplay between these two peaks, between land and sea, serve to remind us of the importance of this image as a depiction Mother Nature and her extraordinary power. Indeed, Hokusai’s work has inspired many other creatives, among them Claude Monet, who partook in Japonisme – the 19th century craze for Japanese art – and Claude Debussy, whose orchestral composition ‘La Mer’, arranged for piano in 1905, featured ‘The Great Wave’ on its first edition cover.

Claude Monet, Impression, sunrise, 1872, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, France

A work by possibly the best-known of the Impressionists, Claude Monet’s Impression, soleil levant (Impression, sunrise) is one of six very similar compositions, each of which offers a view of the port of Le Havre – Monet’s hometown – at a different time of day. In this painting, two small fishing boats drift across the water behind which a red sun pierces through the heavily clouded, foggy sky. This bright sunshine has been interpreted as Monet’s ode to the revitalisation of France following the country’s defeat during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. Exhibited at a Paris exhibition held by the group of ‘Painters, Sculptors, Engravers etc.’ in 1874 – alongside works by artists such as Degas, Pissarro, Renoir and Sisley – it is thought that Impression, sunrise is the painting that inspired the name of the Impressionist movement. When asked for a title for the work, which was to be included in the accompanying catalogue to the exhibition, Monet simply said ‘put Impression’, or so the story goes. Nevertheless, it is a fitting title and description for this hazily-painted masterpiece.

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1927, Museo Reina Sofìa, Madrid, Spain

Picasso’s powerful painting, Guernica, is a political statement on an enormous scale. Created by the artist in response to the devastating bombing of the Basque town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War, it was first exhibited at the 1937 Paris International Exposition, where it gathered little traction. The mural then, however, travelled to a number of locations across the globe as part of a touring exhibition raising funds for the Spanish war relief, and it was then that interest in the work grew. Painted over the course of 35 days, during which the artist’s muse, Dora Maar, documented the work’s development, Guernica was created using ordinary house paint, as Picasso wanted to achieve a matte finish across the entire canvas. The result is a stark, indeed horrifyingly direct, depiction of the suffering endured by countless innocent Spanish civilians. What makes the image all the more imposing is its scale, measuring over 7 metres wide and over 3 metres tall. Picasso was clearly intent on forcing viewers to confront the tragedy that conflict brings.