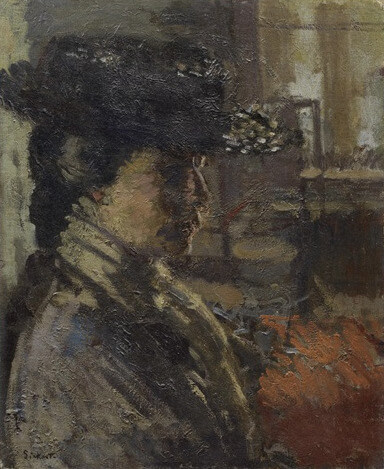

Virginia Woolf, in her 1934 essay Walter Sickert: A Conversation, concluded that the artist “always seems more of a novelist than a biographer…He likes to set his characters into motion”. Born in Munich in 1860 to a German-Danish father – who was also an artist – and an Anglo-Irish mother, Sickert was relocated to England at the age of eight. Despite his education in London – which included a year at the Slade before his characteristic nonconformity prompted him to abandon formal academic education – and his eventual settling in Camden, he would return frequently to the Continent, spending extensive time in France as well as in Venice. An exceptionally innovative artist, his impulse towards experimentation is apparent when tracing the development of his work, from his earliest plein-air landscapes in muted oils, to his shift towards studio work and the eventual emergence of a brighter palette. His use of photographs and news clippings, which he appropriated and reinterpreted within his compositions, was particularly pioneering, prompting a “rich international tradition of painting that frankly acknowledges its photographic origins, which was extended subsequently by the likes of Francis Bacon, Gerhard Richter [and] Chuck Close” (Martin Hammer).

Walter Richard Sickert, Self Portrait, c. 1896, Leeds Art Gallery

Sickert’s work features a variety of subject matter. Time in London saw the formation of the Camden Town Group, a group of English Post-Impressionists which included Wyndham Lewis and Augustus John, and led to some of his most famous work, such the Camden Town Murders series of 1907-09. From the 1880s, much of his work centred around music halls, which brought controversy for their perceived vulgarity. The consistency within his work derives not from his subject matter, which was compellingly broad, but from an atmospheric theatricality offered by his palette choices and innovative angles. For Sickert, formerly an actor, this was perhaps instinctive.

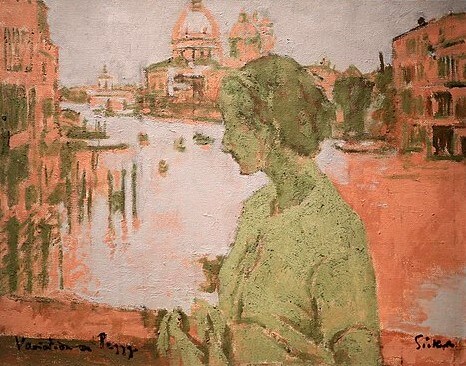

As accomplished as his unsettling figural studies were his landscapes. Sickert produced paintings and sketches of Dieppe, the fashionable Normandy resort visited by the likes of Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley – the latter of whom he painted – until he returned to England permanently in 1922. Images of Dieppe suggest pensive observation, and the interaction between the light and the town’s architecture is acutely rendered in beautifully muted tones. The influence of his two primary mentors – James McNeill Whistler, for whom he worked as a studio assistant when he first travelled to France, and Edgar Degas, whom he encountered in Paris shortly afterwards – can be consistently identified, although arguably it was Degas’s encouragement of indoor painting that ultimately defined Sickert’s practice of working in a studio from drawings. This eventually transformed into his novel method of composing from photographs. Sickert’s landscapes illustrate these influences, synthesising Degas’s technique of close examination with Whistler’s atmospheric pictorial detail, whilst also exuding his own characteristic melancholy. The influences of Whistler and Degas, as well as Sickert’s command of light and his evocative, grey-toned palette are also present in his paintings of Venice, which he visited initially in 1894 and returned to intermittently throughout the subsequent decade. Jean, Lady Hamilton, who had met Sickert off the island of Burano and who owned some of his

Venetian landscapes, praised his views of Venice and Dieppe as “full of appeal – sad – wan – touching”.

Walter Richard Sickert, The Rialto Bridge and the Palazzo Dei Camerlenghi, 1901-02, oil on canvas, currently offered for sale by Simon C. Dickinson Ltd.

The Rialto Bridge and the Palazzo Dei Camerlenghi, likely painted 1901-02, is an exceptional example of Sickert’s Venetian work, and is offered for sale by Dickinson in the gallery’s exhibition at Frieze Masters (11-15 October, The Regent’s Park, London). Antonio da Ponte’s 16th Century bridge is virtually synonymous with Venice, yet, despite having been depicted by a multitude of artists, the landscape is given a unique dynamism within Sickert’s composition. The river becomes one of the characters Woolf spoke of, “set…into motion”. The water is mobile, and dexterous use of purples and greens gives it an almost metallic sheen. It shifts to warmer orange where the sun meets the river at the left of the painting and a small bright orange building above the bridge contrasts with the low-toned palette, implying late afternoon sun. It is a wonderful display of Sickert’s ability to capture light, as well as of his typical early palette.

Walter Richard Sickert, Variation on Peggy, c. 1934-35, Tate Gallery, London

In 1895, Sickert wrote to the artist and fellow member of the New English Art Club, Philip Wilson Steer, that “Venice is really first-rate for work….and I am getting some things done”, and the influence of the city upon his art persisted. His Variation on Peggy (1934-35), depicting the actress Peggy Ashcroft, was inspired by a newspaper clipping and features planes of loosely applied, unnatural colours characteristic of his later experimental work. Nonetheless, it reveals the consistent and enduring inspiration that the city of Venice provided Sickert throughout his career.

Sickert is relatively unique within the Camden Town Group in that he received recognition within his lifetime. Whilst his depictions of music halls were deemed inappropriate – when he first exhibited his Second Turn of Katie Lawrence at Gatti’s at the New English Art Club in 1888 it was labelled both “grotesque” and “shocking” – they nonetheless attracted attention. His venture towards portrait painting did not benefit him financially, and his time in Dieppe and Venice was initially complicated by a lack of regular income. Nonetheless, his landscape works found a ready market though his dealers in Paris, and his paintings of Venice in particular appealed to the burgeoning British enthusiasm for La Serenissima which had followed the earlier publication of John Ruskin’s Stones of Venice. His charm facilitated connections – as indicated by the range of sitters he painted, such as the singer Elizabeth Swinton – but also gained him some patrons, such as Jean, Lady Hamilton. His first retrospective was organised during his lifetime, and was held at the National Gallery in 1941, and there were several displays to mark the centenary of his birth in 1960, including one at the Brighton Royal Pavilion in June 1962. However, “after his death, Sickert remained a notable but underestimated figure. His work was well represented in the nation’s public galleries, but he was perceived as problematically independent of the major identified movements in British art” (Nicola Moorby), contributing to a decrease in market interest in his art.

Walter Richard Sickert, Katie Lawrence at Gatti’s, c. 1888, oil on canvas, Art Gallery of New South Wales

In recent years, however, there has been increasing focus and excitement surrounding Sickert’s work. His Venetian works were the subject of a dedicated exhibition at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in 2009, and since then interest has only continued to rise. In Moorby’s words, “his work was reassessed and his importance revaluated”: a 2021 exhibition titled Sickert: The Theatre of Life at Piano Nobile focused on his figures, and he was featured prominently abroad in the 2019 Hungarian National Gallery exhibition focusing on the School of London and its origins. Interest has rapidly developed, and the Walker Art Gallery held the first major retrospective of his work in thirty years in 2021-22. He was the subject of the first Tate Sickert retrospective in over sixty years at Tate Britain in 2022, and the exhibition moved to the Petit Palais, Paris, immediately afterwards.

The Recent Market for Sickert

An overdue rise in academic attention paid to Sickert has led to an increasingly excitable market for his work. All of Sickert’s best sale results have been achieved post 2010 and at Dickinson we see a wider and deeper market for his works emerging, which usually precedes further increases in prices. Some highlights follow:

Walter Richard Sickert, Bonne Fille, c. 1904-05, Private Collection

In June 2023, an oil on canvas painting of a girl, titled Bonne Fille, exceeded its estimate of £30,000-£50,000 and sold at Sotheby’s for £196,850.

Walter Richard Sickert, Le Corsage Violet, 1907-08, oil on canvas, Private Collection

Sickert’s auction record was set in 2013 when Bonhams sold Le Corsage Violet for £290,500. The previous record, achieved three years earlier, was for a view of Venice. Sotheby’s brought the hammer down on Vue du Palazzo Montecuccoli, dit Aussi Palais Polignac, Venice at £264,750.

Walter Richard Sickert, Vue du Palazzo Montecuccoli, dit Aussi Palais Polignac, Venice, c. 1901-04, oil on canvas, Private Collection

Sickert’s views of Venice continue to be popular with collectors and, as such, perform well at auction.

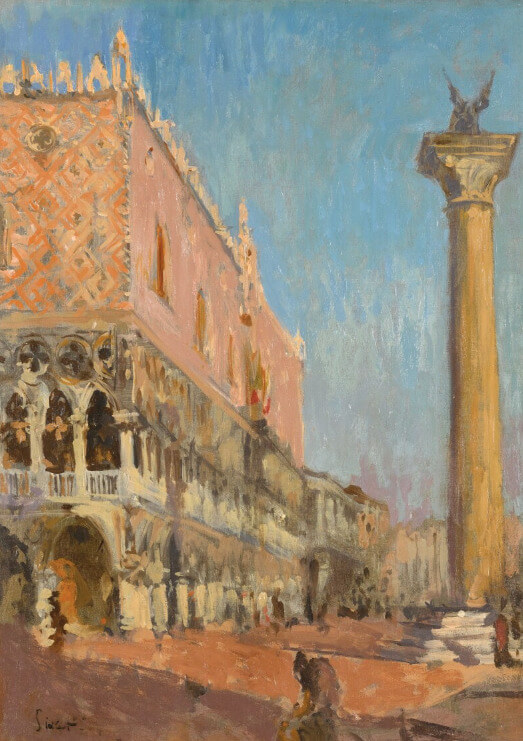

Two of the strongest works of this type to have appeared, Santa Maria della Salute and The Lion of St Mark and the Doge’s Palace, Venice, achieved £145,250 and £100,000 respectively.

Walter Richard Sickert, Santa Maria della Salute, c. 1901, oil on canvas, Private Collection

Walter Richard Sickert, The Lion of St Mark and the Doge’s Palace, Venice, oil on canvas, Private Collection

In all, Sickert is clearly enjoying not only a scholarly renaissance, but a commercial one too. He is clearly a painter whose works we should be paying closer attention to.