Paolo Uccello, The Hunt in the Forest, c. 1470

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

1. Paolo Uccello (1397 – 1475)

Bridging the gap between Gothic and Renaissance, the Florentine painter Paolo Uccello used animals as a vital tool in his quest to make sense of the visual world around him. Vasari tells us that Uccello was so obsessed with mastering the depiction of perspective that he would work night and day, much to his wife’s chagrin. What makes Uccello a great animal painter (and the first on this list) is how his pioneering use of one-point perspective was applied to the animals in his pictures.

This painting is his last known work and, in many ways, his most complex achievement. Uccello presents us with a panoramic view of huntsmen both mounted and on foot, surrounded by a pack of sighthounds, chasing deer into the dark central vanishing point of the picture. To create the illusion of depth, he has had to paint his horses and (somewhat medievally stylised) hounds either in profile or facing diagonally towards the vanishing point. All the animals conform to this rule and, although highly contrived, it results in what is perhaps the first spatially coherent depiction of animals in a landscape.

Albrecht Dürer, Young Hare, 1502

Albertina, Vienna

2. Albrecht Dürer (1471 – 1528)

A true Renaissance man, Dürer could turn his hand to most things, whether that be penetrating self-portraits, a huge and varied body of printed and drawn works, or, of course, the production of religious painting. One vein that runs throughout all of his practices is a predisposition for the intricate. This is especially evident in his woodcuts which layer tiny symbolic detail over often complex, stylised forms to create a dense, meaning-laden image. When he wasn’t inventing intricacies of his own, Dürer seemed happy enough to observe them in nature. He completed painstaking depictions of plants and animals, obviously delighting in reproducing the minutiae of their constructions with the utmost fidelity. Remarkable for the accuracy and clarity of its treatment, is Dürer’s Young Hare perhaps the first photo-realistic artwork?

Frans Snyders, Boar Hunt, c. 1625 – 1630

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

3. Frans Snyders (1579 – 1657)

Snyders was one of the first ‘animaliers’, or painters who specialised in depicting animals. Taught by the great animal painter Pieter Breughel II and Hendrick van Balen, Snyders had some of the best artistic training that Flanders could provide. After a trip to Italy in 1608-09, Snyders returned to his native Antwerp to pursue a career as a painter of animals. Snyders’ most notable works are probably his hunting pictures. These scenes are memorable because, more often than not, they do not include huntsmen – rather, they focus on the combat between the animals themselves. By shifting this focus, Snyders was able to explore each animal’s physical attributes and state of mind. Through a mix of facial expressions, bodily contortions and gory detail, we are made fully aware of the pain suffered by the quarry and the bloodthirstiness of the hounds that pursue.

Paulus Potter, The Young Bull, 1647

Mauritshuis, The Hague

4. Paulus Potter (1625 – 1654)

Despite his incredibly short life (Potter died of tuberculosis aged just twenty-eight), Paulus Potter is perhaps the best-loved animal painter of the Dutch Golden Age. Potter primarily specialised in depicting cattle and horses and did so with a subtle and unlikely blend of supposed realism and idealism. The prime example of this combination is undoubtedly his masterpiece, The Young Bull. The bull depicted here is in fact a creation of Potter’s, an ideal composite constructed of studies taken from several beasts. In doing this, Potter gives the illusion that the eponymous bull is a perfectly observed creature; the hairs on its hide are individually delineated as are the numerous flies that buzz about it. Yet despite this warts-and-all approach, Potter places this bull at the centre of his monumental canvas where it acts not only as an ideal specimen of its species but as a symbol of Dutch prosperity.

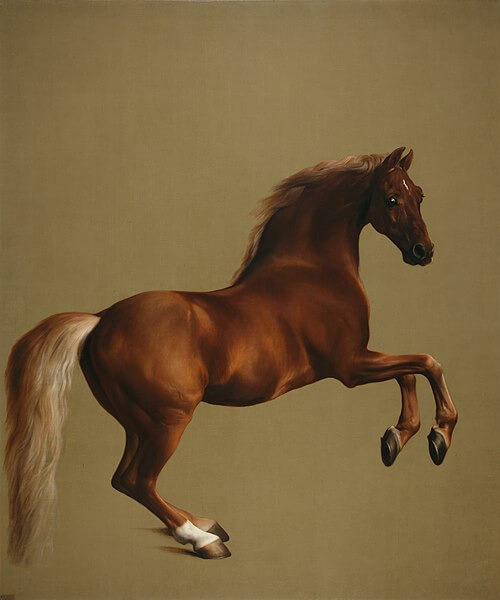

George Stubbs A.R.A, Whistlejacket, 1762

National Gallery, London

5. George Stubbs A.R.A (1724 – 1806)

Stubbs was a master of depicting all manner of animals; dogs, lions, tigers and even kangaroos appeared from beneath his brush. He is, however, all but unanimously accepted as the greatest horse painter of them all. The origin of Stubbs’ unique ability were the years he spent locked away in a Lincolnshire farmhouse, dissecting horses and making detailed anatomical drawings later published as The Anatomy of the Horse. The understanding Stubbs gained from this study gave him a marked advantage over horse painters of the previous generation, such as Wootton and Seymour. Stubbs put his skills to good use and painted innumerable pictures of horses with remarkable accuracy. Stubbs’ grounding in anatomy also allowed him to depict the animal in a more lyrical manner than ever before, horses as protagonists in their own right. Nowhere is this more apparent than in his most celebrated picture, Whistlejacket, the Marquess of Rockingham’s racehorse. Depicted life-size, the thoroughbred rears on its hind legs and looks the viewer in the eye in a remarkable show of strength and self-assurance. Even more radical is the picture’s blank background, which focusses our attention on the artist’s magnificent subject, creating the powerful image so loved by visitors to the National Gallery today.

John James Audubon, Whiteheaded Eagle, 1827

Plate 31 of The Birds of America by John James Audubon

6. John James Audubon (1785 – 1851)

John James Audubon was as much an ornithologist as an artist. Audubon is best known for his magnum opus, The Birds of America, which, as the title suggests, is a richly illustrated survey of all things American and avian. Born in the French colony of Saint-Domingue and raised in France, Audubon was moved to America by his father to avoid his conscription into Napoleon’s navy.

Fascinated by birds since childhood, Audubon turned his full attention to their study around 1820 after a patchy career as a mine owner and trader. He travelled widely, hunting birds that he could either turn into taxidermy or position with the use of wires and weights with the purpose of drawing them with great accuracy.

In its finished state, The Birds of America consists of over four hundred species which were engraved and hand coloured by an army of assistants. Audubon was keen to show his birds in motion, which, paired with bold colouring, created dynamic, appealing images. This helped scientifically as it allowed him to show each bird in multiple different positions. Another features of the work is the fact that each bird is rendered lifesize, meaning that some of the larger creatures’ bodies are somewhat contorted in order to fit onto the page. In creating this work, Audubon not only produced the most accurate ornithological survey to date, but did so in a way that placed artistic depiction on an equal footing to scientific exactitude. The Birds of America frequently tops lists of the most expensive printed books ever sold.

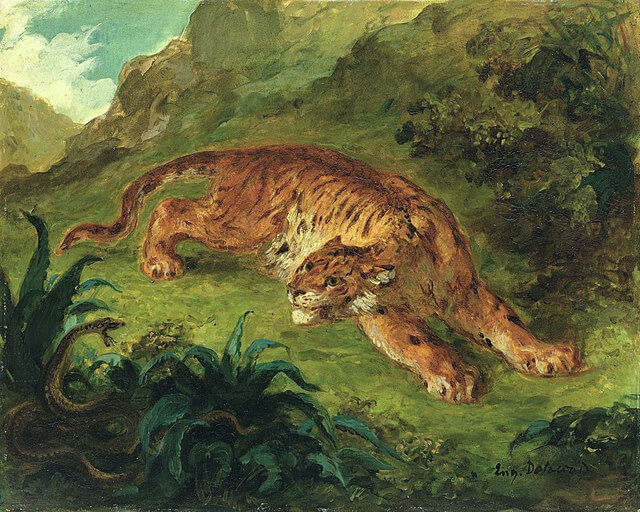

Eugène Delacroix, Tiger and Snake, 1858

Hamburger Kuntshalle, Hamburg

7. Eugène Delacroix (1798 – 1863)

The epitome of the French romantic artist, Delacroix enjoyed a career that was built on the foundations laid by his friend and mentor, Théodore Géricault. Reacting to his older friend’s 1819 masterpiece, The Raft of the Medusa, Delacroix announced his career with fraught and dramatic modern history paintings such as The Massacre at Chios and Liberty Leading the People. Delacroix had no trouble transposing the romanticism of his history paintings to depictions of animals. He chose wild, untamed beasts as his subjects. Lions, tigers and leopards abound, often locked in mortal combat. Influenced heavily by Stubbs’ romantic treatment of animals – namely his series of horses being attacked by lions – Delacroix takes this prototype but replaces Stubbs’ restrained brushwork with his own wild, rapid handling.

Sir Edwin Landseer R.A., Eos, 1841

Royal Collection, London

8. Sir Edwin Landseer R.A. (1802 – 1873)

Landseer is the best-known animal painter of the Victorian era. He was beloved not only by his royal and aristocratic clients but also by a British public who decorated their homes with printed reproductions of his work. Landseer painted an enormous range of creatures from birds to monkeys and horses to polar bears. Further to this, he sculpted the Trafalgar Square lions and produced perhaps the most enduring image of the Scottish Highlands, The Monarch of the Glen. He was a master of anthropomorphising animals through paint. This picture is of Eos, the beloved greyhound of Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s consort, and she was clearly a very fine, sleek creature. Albert’s presence is felt through his discarded top hat, gloves and cane. Eos appears to be looking up at her owner, just out of view. Landseer ingeniously mirrors Eos’ coat in the beaver fur top hat and nods at her white markings through the inclusion of the pristine gloves and ivory cane top. In doing all this, Landseer did not simply create an impressive and anatomically exacting depiction of a dog; rather he equated the hound to its owner who, like Eos, we are told is elegant, and crucially, well-bred.

Henri Rousseau, Surprised!, 1891

National Gallery, London

9. Henri Rousseau (1844 – 1910)

Rousseau is the first artist on the list whose work was apparently not interested in the accurate anatomical depiction of creatures. An entirely self-taught artist, Rousseau was a Parisian tax collector by profession and only turned his hand to painting in a serious manner when he was in his late forties. His lack of academic training is immediately evident. His paintings are naïve, partially due to the fact that he often used illustrated children’s books as inspiration. The curious thing is that his animal paintings almost exclusively take the jungle as their setting despite the fact that he never left his native France. He instead used trips to the botanical gardens in Paris to ignite his imagination. Surprised! is housed in London’s National Gallery. Rousseau’s technique involved the meticulous building up of paint layers to create a polished and controlled surface to his canvas. He also manages to imbue the tiger with all the danger and aggression it is popularly imagined to have.

Sir Alfred Munnings P.R.A., R.W.S., R.P., K.C.V.O, Frank Freeman and his Hounds, c. 1929

Previously with Dickinson

10. Sir Alfred Munnings P.R.A., R.W.S., R.P., K.C.V.O. (1878 – 1959)

In many ways an heir to Stubbs, it is no exaggeration to claim that Alfred Munnings was one of the great horse painters of art history. Munnings worked through the first half of the twentieth century but, being the staunch traditionalist (and an outspoken opponent of modernism) that he was, his art was primarily concerned with the timeless evocation of English sporting and countryside life.

Munnings grew up as a rural Suffolk miller’s son, meaning his formative years were spent surrounded by and observing the horse-drawn agriculture of the late Victorian period. He received artistic training in Norwich. His early work which followed took rural scenes of gypsies and their horses as its subject. After working as a war artist towards the end of World War One, Munnings transitioned his career into that of a fashionable society horse painter and portraitist. His best works are a combination of several elements: a perfect understanding of anatomy, sleek and elegant portraiture (not dissimilar to that of contemporaries such as de Lazlo), effortless impasto brushwork, and an Impressionistic understanding of colour. Munnings’ dazzling technical proficiency and patrician clientele ensured his ascent to the highest rank of artistic life: a knighthood and the Presidency of the Royal Academy from 1944-49.

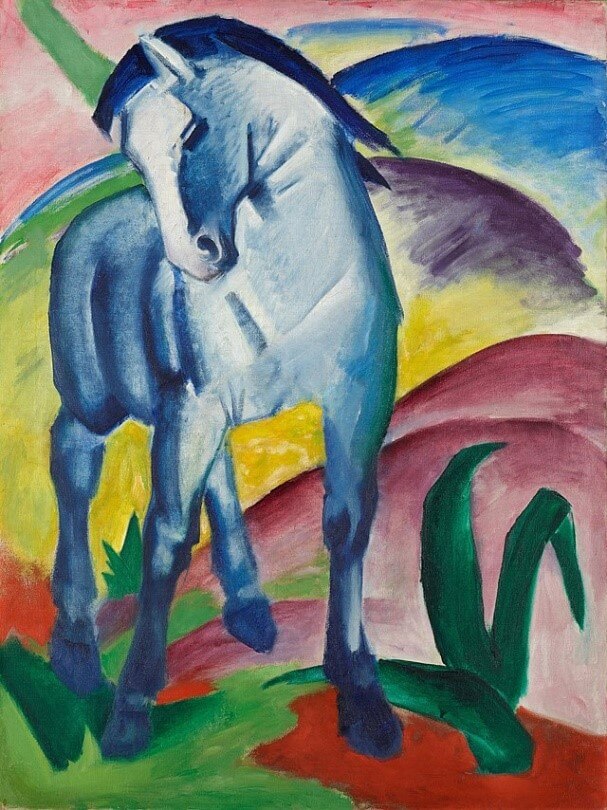

Franz Marc, Blue Horse I, 1911

Lenbachhaus, Munich

11. Franz Marc (1880 – 1916)

A leading proponent of German Expressionism and Modernism (and presumably no friend of Alfred Munnings), Franz Marc had his life cut tragically short on the battlefield at Verdun. Before his early death at the age of thirty-six, Marc had been a founding member of Der Blaue Reiter, a journal and artistic collective that took artistic inspiration from a wide range of sources such as folk art from the Pacific and Russia, Japanese prints and, like Rousseau, children’s books. By combining these stylistic elements, Marc created dreamlike depictions of animals – particularly horses – using bold brushwork and colours. A sense of calm and peace pervades Marc’s work. The bright primary colours of the landscape are joyous whilst the ubiquitous blue of the horses produce a more spiritual, reflective reaction. Marc not only used horses as a spiritual vessel for his paintings, but was evidently fascinated by their form. In this painting, the horse is delineated almost exclusively in straight lines which prefigures his full adoption of a Cubist approach the following year.

Lucian Freud O.M., C.H., Pluto, 1988

Private Collection

12. Lucian Freud O.M., C.H. (1922 – 2011)

A real titan of British art and one of the greatest figurative painters of the last century, Lucian Freud painted portraits that are always imbued with immense psychological insight. Freud’s painting technique changed almost beyond recognition in his career of over seventy years. Early animal works often feature strangely juxtaposed creatures (often birds), somewhat surrealistically placed, painted or drawn with precise lines and on a minute scale. These rather un-painterly early efforts soon made way for his bolder, impasto lade later style.

In a very English tradition, Freud was a lover of horses and dogs, but he also saw animals as individuals in a human sense. He subjected them to the same levels of artistic scrutiny and in them found all the personality of his human sitters. In much the same way, Freud saw his human sitters as creatures and, as such, often painted them naked. Freud was an admirer of animals’ temperaments above all things and it is possible to detect rather more warmth in his depictions of canines than in those of their owners – something evident in this study of his favourite pet whippet, Pluto.