When we talk about ‘Concrete art’ (and its successor, the ‘Neo-Concrete’ movement) – the theme of Perspective: Visible and Tangible Form, our recent stand for TEFAF New York 2022, and the ongoing exhibition at 980 Madison – rest assured we’re not planning to hire builders to fill the room with actual concrete! (Not that that’s a bad idea…but Rachel Whiteread got there first.)

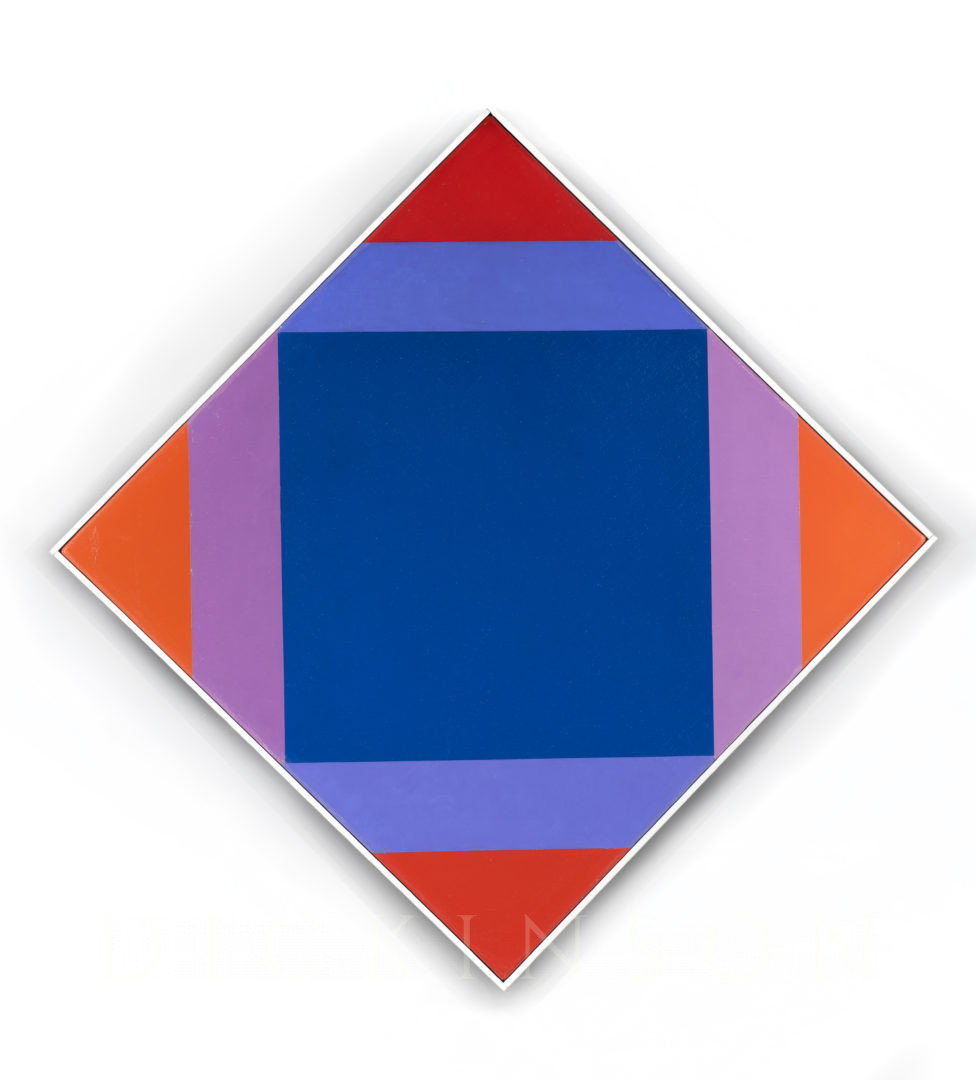

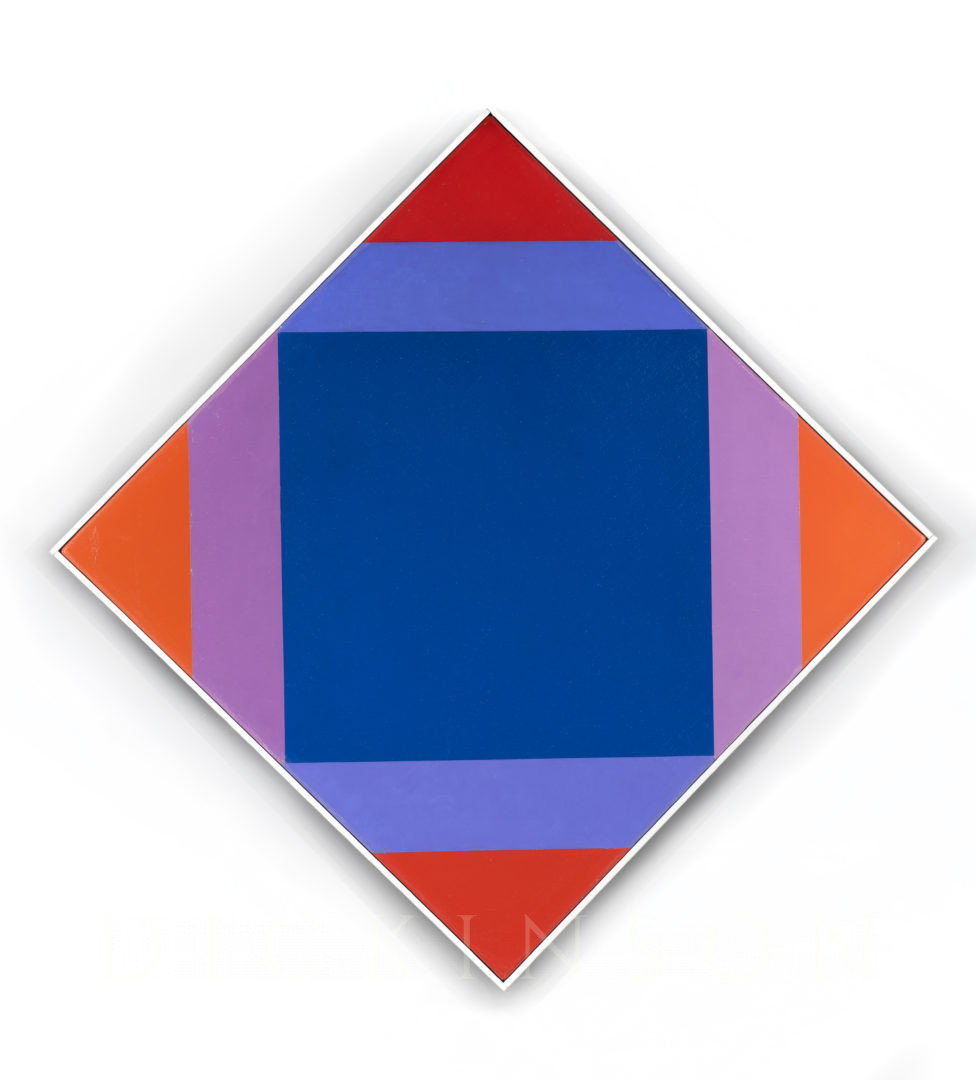

The term Concrete art in fact refers to a movement centred on artworks that emphasise geometrical abstraction, with strong horizontal, vertical and diagonal lines often reminiscent of modern architecture. The term was originally used by Dutch artist, author and architect Theo van Doesburg, who – along with Piet Mondrian – founded the De Stijl movement in 1917. The pair fell out in 1924 over the issue of diagonals, which Mondrian rejected in favour of strict horizontal and vertical lines, but which Van Doesburg promoted for their dynamism.

Following the dissolution of the Mondrian-Van Doesburg partnership, Van Doesburg sought to establish a new artist collective sharing his personal approach to abstraction. He first discussed this proposal with Uraguayan painter Joaquin Torres-García in 1929, but again fell out with his intended collaborator, this time over the issue of abstraction: Van Doesburg championed purely abstract art free of any identifiable references, while Torres-García believed in maintaining ties to referentiality. The two went their separate ways, with Torres-García and his group forming the Cercle et Carré and Van Doesburg joining fellow artists Otto Carslund, Jean Hélion and others in a group dubbed Art Concret; Van Doesburg felt that the term ‘abstract’ already carried too many associations. Art Concret, or Concrete Art, declared in its manifesto a universal aim: to find inspiration purely in its individual components, the line, the plane and colour, rather than in the subjective realm.

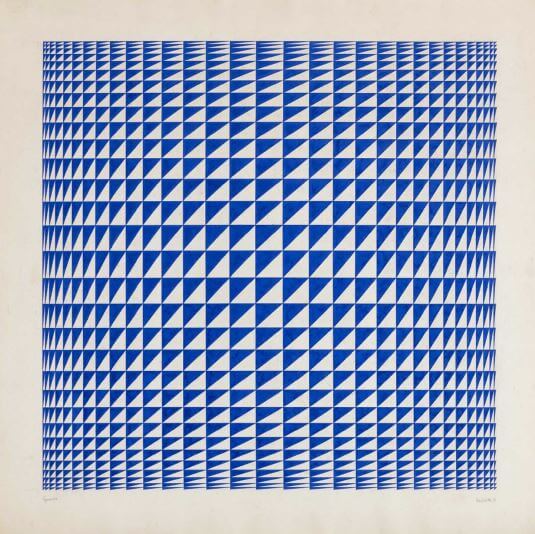

After Van Doesburg died in 1931, fellow advocates of the Concrete Art manifesto helped to promote the movement more widely, both in Europe and in Latin America. One of the most significant contributors to this effort was Max Bill, the Swiss artist, architect and graphic designer, who studied at the Bauhaus and is credited with organising the first international exhibition of Concrete Art in Basel in 1944. It was Bill who, in 1951, brought Concrete Art to Latin America with his 1951 retrospective at the São Paulo Museum of Modern Art. Bill’s work, and the Concrete Art style, seemed to many young Brazilian artists the ideal language to reflect a rapidly modernising mid-century Brazil. Among them, Luiz Sacilotto was one of the innovators of Brazilian Concrete art, and was hailed by Waldemar Cordeiero, leader of the Ruptura group, as the ‘structural beam’ of Concretism in Brazil. Augusto de Campos, the Concrete poet, writer, and friend of Sacilotto, further identified his work of the 1950s as precursor to Op-Art, claiming that the Brazilian was experimenting with this art form before Victor Vasarely, who is widely recognised as the father of the movement.

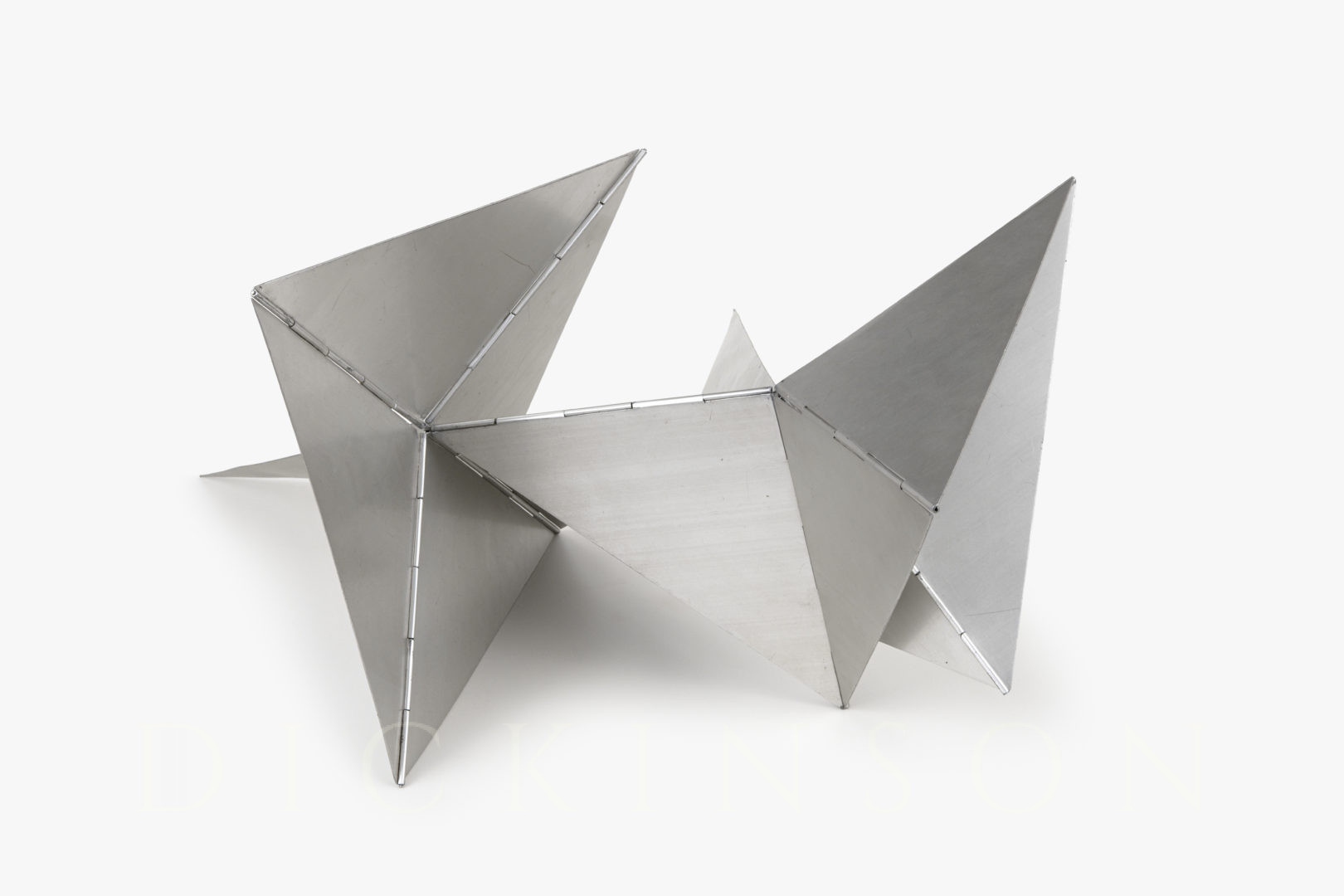

The Brazilian Neo-Concrete movement was a splinter group that emerged from the Grupo Frente, based in Rio de Janeiro, existing only briefly in the years 1959-61 before breaking into factions. Concrete art first found success in Latin America because its pure abstraction and non-objectivity made it palatable to the repressive governments controlling the region. Neo-Concretists preserved abstraction but differed in an increased sense of poetry and emotionality, feelings absent from pure Concrete art. Among the leaders of this new wave of artists were Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape and Hélio Oiticica. The group’s manifesto was authored by the poet Ferreira Gullar in 1959, and described an artwork as ‘something which amounts to more than the sum of its constituent elements; something which analysis may break down into various elements but which can only be understood phenomenologically.’ In other words, although the work itself may be abstract, it must transcend the limitations of non-representation to express the complexities of human existence. It can draw on elements of time and space as well as those of line and plane. Other artists, although associated with the movement, resisted clear categorisation. While her work was informed by Neo-Concretists such as Hélio Oiticica, Sergio Camargo, Lygia Clark and Lygia Pape, Mira Schendel never officially joined the Neo-Concrete group nor the subsequent Tropicalia cultural movement, due in part to her fierce independence. Also working at the periphery of the movement was Alfredo Volpi, whose Neo-Concrete influences were combined with his love of architecture and filtered through the lens of his Italian origins.

Right: M. Schendel, Sem título (Dec. 1960), 1960, oil on canvas

Perspective: Visible and Tangible Form is not the first time Dickinson has staged a Neo-Concrete show. The gallery’s 2012 exhibition featuring works by Ivan Serpa was among the earliest shows with this theme to take place in North America.

To enquire about the availability of the above works, please click here.