Anyone who has visited one of Dickinson’s art fair stands in recent years will have noticed our scholarly catalogues. These are a cross between an auction house catalogue and a museum exhibition catalogue (albeit put together with a considerably smaller team than the former and on a much shorter time frame than the latter!) Today’s insight gives you a closer look at the complex process of producing a catalogue.

With four to five fairs a year to plan, and artworks coming in on consignment until the last minute, we don’t have a great deal of lead time. Despite our best efforts to be organised in advance, there is always something to resolve at the last moment.

When artworks first come into the gallery, they are catalogued by Head of Research Molly Dorkin, who uses artists’ catalogues and online databases to record a work’s provenance (known history), literature references and exhibition history. Labels or stencils on the reverse of a painting can also yield information about a work’s history, as can our own notes in old auction catalogues. Some works need additional expertise, which means writing to the recognised authority or committee for a certificate of authenticity. The works are also professionally photographed.

The Old Masters library at Dickinson London

The next stage is research and writing: literature references need to be checked and scanned at various libraries (with the assistance of Gallery Manager Max Weaver, Old Masters Administrator Fraser Short, and of course our reliable interns). Molly will write a brief, hopefully interesting, essay on the relevant artist or artistic movement, sometimes working closely with a noted expert such as Picasso scholar Marilyn McCully. All of the essays are checked by Head of Impressionist and Modern Art James Roundell, who catches every error, from the smallest typo to a missing catalogue reference.

Gallery Manager Max Weaver inspecting the labels on the back of a painting

Writing text is the easy part, but the catalogue then moves into the design phase, with Managing Director Emma Ward setting a scheme for the catalogue and stand that will play on a consistent colour palette and general aesthetic. Emma and Molly will meet with Lara or Maria, our consultant graphic designers (and ex-Dickinson staff), to explain the project and its parameters – it is then up to the designer to choose everything from the shape and format of the catalogue to the font, layout and cover design. Fraser and Max supply images of the relevant artworks as well as general images – perhaps a photograph of an artist at work, or with a model; or images of works in museums that relate to the pieces offered for sale. These all have to be scanned and sent, along with their captions. In many cases we also have to apply for copyright permission from an artist’s estate.

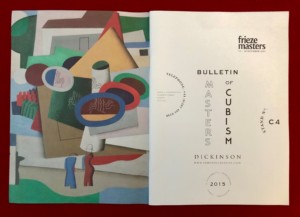

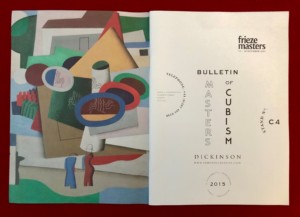

Frontispiece of the catalogue for Frieze Masters 2015

Once the designer has gone back and forth on several drafts with Molly, to proof for corrections and edits, the document is sent to our printer (who is generally fretting at this stage over concerns about timing – especially if we have chosen a labour-intensive, hard-cover catalogue!) He still has to send us a printer’s proof so we can colour-check the images for accuracy; choose endpaper colours; and correct any final typos or add expertise that has come in at the last moment. Only then can we officially go to press. While we are awaiting the printed catalogues, the designer sends us a digital one to begin advertising the upcoming fair.

The feedback on our catalogues from consigners and buyers alike makes the process worthwhile: putting an artwork, or a collection, in context; providing accurate, scholarly information; and presenting our research in a printed catalogue helps us show off the artworks – and our stands at fairs – to their best advantage. But if you spot a typo…please don’t tell us!