‘Here is the man who has meditated on all things modern, here is the painter who wishes to invent only new compositions, who would draw and paint only materially pure forms’ (Guillaume Apollinaire, 1913)

Most people, if asked to name a Spanish Cubist, would have a single answer: Picasso. His fame is such that it easily eclipses that of his fellow innovators in the early years of the 20th century, among them the Spaniard Juan Gris, whose early death in 1927, aged 40, cut short a brilliant career. Thankfully, scholars are seeking to remedy this, and to bring Gris to the attention of a wider audience. Cubism in Color: The Still Lifes of Juan Gris, which opened on 18 March at the Dallas Museum of Art and will next travel to the Baltimore Museum of Art, marks the first exhibition dedicated to Gris in the United States in over 35 years, and features nearly 40 paintings and collages executed between 1911 and 1926.

Installation of Cubism in Color: The Still Lifes of Juan Gris, Dallas Museum of Art, TX, photograph by Chadwich Redmon, courtesy Dallas Museum of Art

Apollinaire once called Gris ‘the demon of logic’, and his ability to straddle the boundary between abstraction and representation was second to none. Born in Madrid, Gris moved to Paris in 1906. By 1909, he was living with his wife and young son at the Bateau-Lavoir – the ramshackle collection of artists’ studios in Montmartre, where Picasso was already in residence. Among his friends, Gris counted the poets Guillaume Apollinaire and Max Jacob, as well as artists Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, Fernand Léger, Jean Metzinger, and, of course, Picasso. He only began painting seriously in 1911, having abandoned a career as the author of satirical cartoons, and exhibited for the first time at the 1912 Salon des Indépendants. In the same year, he signed an exclusive arrangement with dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler.

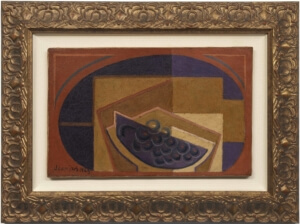

J. Gris, Le raisin noir, 1923, oil on canvas, 22.5 x 33.5 cm, available for sale at Dickinson

The earliest works in Cubism in Color are typical of Analytical Cubism, a term actually coined by Gris himself. This style is characterised by multiple viewpoints and the fragmented, overlapping planes of the subject depicted – usually in a muted or limited palette so as not to detract or distract from the forms themselves. Relatively short-lived, Analytical Cubism was succeeded around 1912 by so-called Synthetic Cubism, which featured simpler, flat, overlapping shapes and often a brighter palette. As Gris himself described it, ‘the only technique is a sort of flat, coloured architecture.’

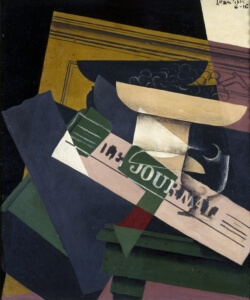

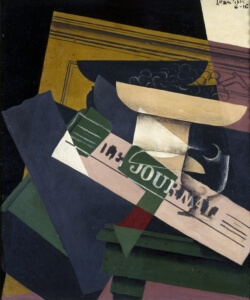

J. Gris, Les Raisins, 1916, oil on panel, 55 x 47 cm, sold by Dickinson to Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

One of Gris’s periods of greatest innovation and brilliance – the years that saw him experimenting with a combination of collage and oil painting, and the introduction of the pointillist dots of ‘Confetti Cubism’ – coincided with the First World War. As a foreign national stranded in Paris, Gris was not obliged to serve in the French army like so many of his artist friends, but he struggled financially. Kahnweiler, exiled to Germany as an enemy alien, was unable to continue paying Gris according to the terms of his contract; it was only in 1915, when Gris was officially released, that he was able to begin dealing with Léonce Rosenberg. Among the many masterpieces dating from this era was Gris’s Les Raisins (1916), sold by Dickinson to Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, and Nature morte à la nappe à carreaux (1915), which set the auction record for any work by the artist when it sold for $57.1 million in 2014. Although the forms are abstracted, they never lose touch entirely with representation, a quality that defines Gris’s style.

Juan Gris in 1926, photograph by Georges Duthuit

Gris gained additional attention and recognition in the following decade, including major exhibitions at Galerie Simon in Paris and Galerie Flechtheim in Berlin in 1923. The years 1924-25 saw him expressing the majority of his aesthetic theories, and delivering his lecture Des possibilitiés de la peinture at the Sorbonne in 1924. He died of kidney failure on 11 May 1927.