Beyond the conventional genres of portraiture, landscape, history painting, still lifes or religious scenes, some artists looked to more unusual subjects for inspiration, among them the field of medicine. From the old masters to the modern era, paintings of medical subjects have offered valuable insights into contemporary practices of scientific enquiry and healing.

L. da Vinci, Vitruvian Man, c. 1490, pen and ink on paper, Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice

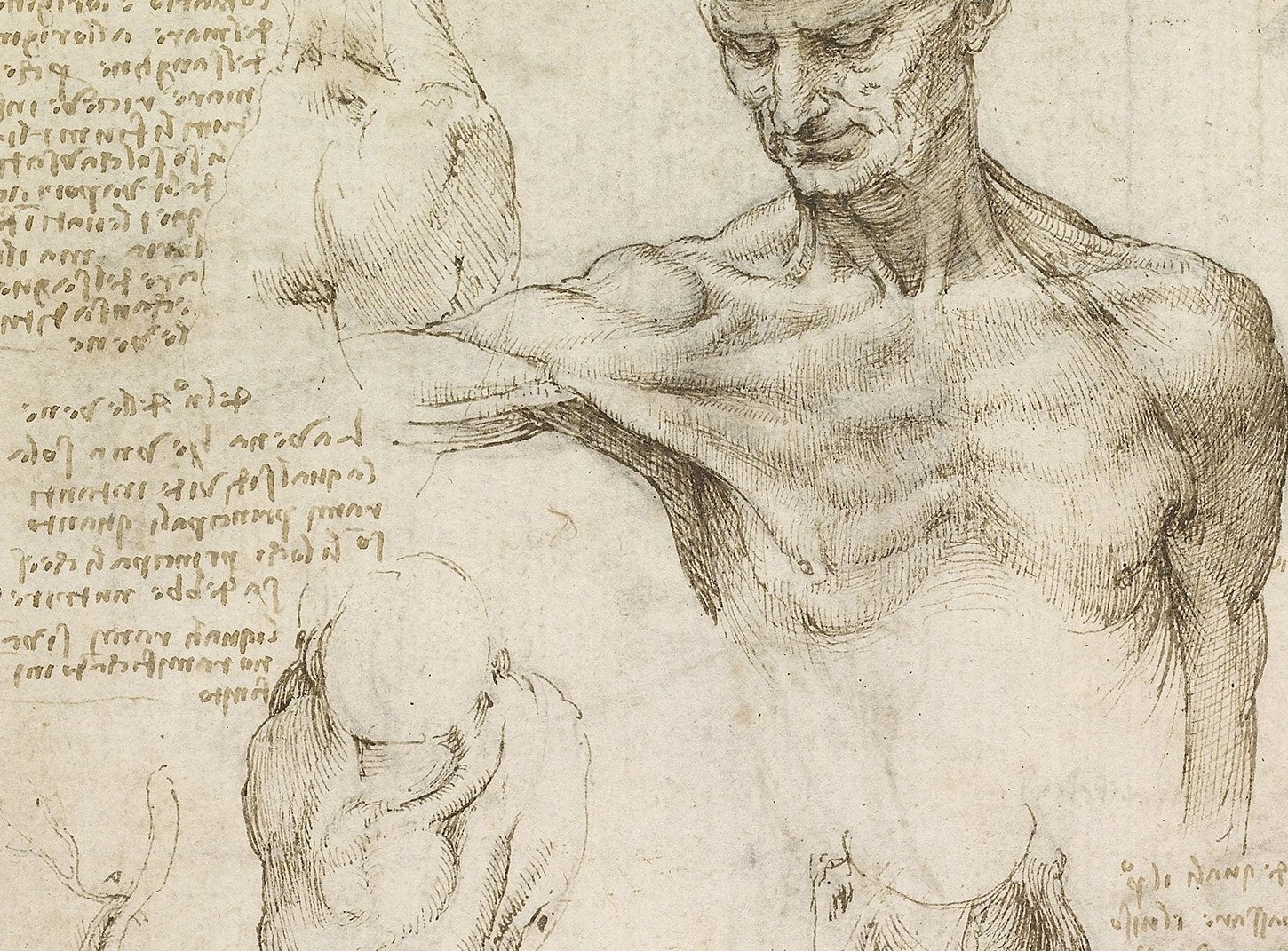

Leonardo da Vinci’s series of medical studies, many of them collected in the artist’s sketchbooks, were intended for scientific study rather than as ‘art’. A talented engineer, inventor, poet, and scientist as well as an artist, Leonardo was originally engaged by an anatomy professor to provide anatomical drawings for a textbook; Marcantonio Della Torre, the anatomist, died before the project began, but Leonardo was eager to continue the mission and began dissecting cadavers – in secret, as it was forbidden by the church – himself. The detailed drawings he produced made substantial contributions to the fields of anatomy, neuroanatomy and neurophysiology.

Rembrandt, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp, 1632, oil on canvas, Mauritshuis, The Hague

Among Rembrandt’s most famous works is his 1632 oil painting The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp (1632). Dr Nicolaes Tulp, the mayor of Amsterdam and official City Anatomist, is seen here demonstrating dissection to a group of fellow physicians and scholars. He is using as his cadaver the body of a hanged criminal – identified as Aris Kindt, condemned for burglary – as criminals were considered outside the church and thus dissection was permitted, albeit only once a year. It was considered, oddly enough, a social occasion, with paid tickets sold and the spectators finely dressed. Rembrandt’s theatre is an imaginary scene, although the individual portraits were painted from life.

J. Steen, The Lovesick Maiden, c. 1660, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

There was as much quack science as genuine medicine depicted in the art of this period. Paintings such as Jan Steen’s The Lovesick Maiden (c. 1660) offer a more comical take on the subject of healing. In Steen’s composition, an elegantly dressed young woman sits forlornly, head in hand, while a quack doctor attempts to take her pulse. Details, such as the pair of copulating dogs in the doorway, tell us the real reason for the young woman’s illness: one for which there is no doctor’s cure. Likewise, dentists were seen as a subject offering comedy value, as we can appreciate in a painting by David Teniers II – from the grimace of the patient, suffering a procedure in the days before anaesthesia, to the determined look of the dentist, who may have had neither actual qualifications nor training (The Dentist, 1652).

D. Teniers II, The Dentist, 1652, oil on panel, Manchester Art Gallery, Manchester

Some artists painted their own doctors out of gratitude. Such was the case with Goya’s Self-Portrait with Dr Arrieta (1820). Goya had developed a serious illness very suddenly in 1792, one that left him completely deaf, and suffered a second episode in 1819. Although the cause of the disease remains unknown – speculations, based on his recorded symptoms, range from syphilis, lead poisoning, and infection of the central nervous system, to a type of plague – Goya was treated successfully by plague specialist Dr Eugenio Arrieta. In this painting, we see Arrieta ministering to the stricken artist, and an inscription reads: ‘Goya, in gratitude to his friend Arrieta: for the compassion and care with which he saved his life during the acute and dangerous illness he suffered towards the end of the year 1819 in his seventy-third year. He painted it in 1820.’

F. Goya, Self-portrait with Dr Arrieta, 1820, oil on canvas, Minneapolis Institute of Art, MN

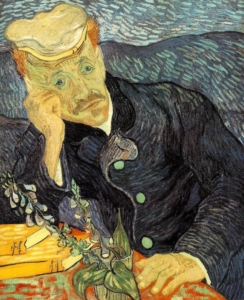

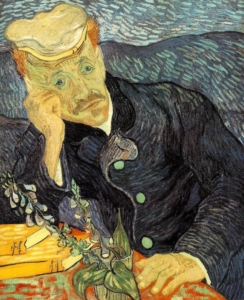

Likewise, Van Gogh’s two versions of the Portrait of Dr Gachet (1890, Private Collection; and 1890, Musee d’Orsay, Paris) depict Dr Paul Gachet, the doctor who cared for Van Gogh during the final months of his life, following his release from the asylum in Saint-Rémy. Unlike Goya’s doctor, shown treating his patient, Van Gogh’s Gachet is seated at a table, leaning head on hand in the classic pose of melancholy. Looking more closely, however, we can identify the purple plant in his hand as the medicinal herb foxglove, and the two yellow books on the table may be medical texts. Van Gogh relied heavily on Dr Gachet during these months, writing to his sister Wilhelmina: ‘I have found a true friend in Dr Gachet.’

V. van Gogh, Portrait of Dr Gachet, 1890, oil on canvas, Private Collection

Two depictions of surgery by American Thomas Eakins, executed some two and a half centuries after Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp, illustrate advancements in the field of medicine. The first, The Gross Clinic, was painted in 1875 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, PA), and shows Dr Samuel Gross operating on a young man to treat osteomyelitis of the femur. Where Rembrandt’s Dr Tulp was carrying out a dissection on a cadaver, Eakins’s Dr Gross is carrying out a procedure to heal a living patient. Moreover, the patient is unmoving thanks to one of the most revolutionary advances in medicine to date: anaesthesia, first used just 29 years prior, during a dental procedure at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

T. Eakins, The Agnew Clinic, 1889, oil on canvas, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

The Gross Clinic wasn’t Eakins’s only foray into painting a medical subject: four years later, Eakins painted The Agnew Clinic (1889), which again demonstrates important advances in the field. Where the surgeons in The Gross Clinic crowd closely around the patient wearing everyday dress – their hands un-gloved, evidently still unaware of the importance of a hygienic environment for surgery – the surgeons in The Agnew Clinic are attired in surgical gowns (albeit still without gloves). Also significant is the presence of two women: the anonymous patient, undergoing a mastectomy; and the nurse, identified as Mary Clymer, the first trained operating room nurse in Philadelphia. Not surprisingly, Eakins’s decision to depict a partially-nude female patient surrounded by male physicians, even in the context of surgery, aroused controversy when the painting was exhibited.

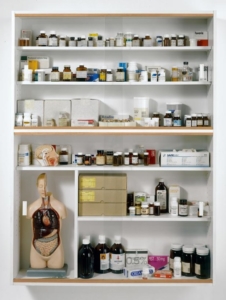

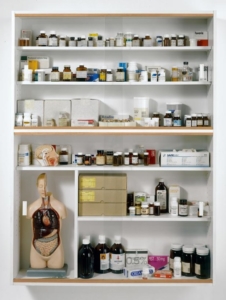

D. Hirst, Sinner, 1988, glass, faced particleboard, ramin, plastic, aluminium, anatomical model, scalpels and pharmaceutical packaging, Collection of the artist, UK

Moving into the 20th century, we have Damien Hirst’s series of Medicine Cabinets, featuring rows of multicoloured pills or pill boxes lined neatly on the shelves of a cabinet. In the first of these, created in 1988, Hirst lined up the empty boxes from his grandmother’s various prescriptions after her death. He observed: ‘You can only cure people for so long and then they’re going to die anyway. You can’t arrest decay but these medicine cabinets suggest you can.’ Hirst’s cabinets seemingly offer a cure for all ills, but ultimately, as he points out, our faith in pharmaceutical cures is still a question of belief and hope rather than certainty.