With over two months of lockdown now behind us, ‘dressing for work’ has taken on a new meaning – after all, will your colleagues really notice you’re in your gym gear, when all they can see is a postage-stamp-sized image over zoom? (Or is that just us?) It may even prompt some contemplation about the nature of clothes and the meaning of dressing – or undressing – in art throughout the ages. And while we wouldn’t recommend taking your cues from the classical nude (at least not for those with a digital meeting scheduled!) we can identify a range of meanings, purposes and messages associated with depictions of nude figures through the ages.

Carlo Saraceni, The Giant Orion, c. 1616-17, oil on canvas

Depictions of the nude, idealised figure were an ongoing preoccupation of Greek and Roman artists, and while we see fewer depictions of the nude in the Middle Ages, this interest was reignited by the artists of the Renaissance and Baroque periods. The nude figure was considered suitable for allegorical or history painting due to its timelessness, and it was acceptable to depict contemporary leaders, as well as mythological ones, as ‘heroic nudes’. In Carlo Saraceni’s The Giant Orion (c. 1616-17), the giant is depicted nude apart from a drapery – an artistic choice that both emphasises his hulking form and underscores the timeless qualities of the narrative. The figure’s specific pose may well have been studied from life. Sir Peter Lely’s A bacchanale with nymphs, a satyr and putti (c. mid-1640s) also offers an example of an academic nude – the figure at far right, with his back turned to us, must surely be based on a life study. (The semi-nude nymphs might have required a bit more imagination, due to the general lack of female studio models – but a fully-clothed nymph is surely a wasted opportunity!)

Sir Peter Lely, A bacchanale with nymphs, a satyr and putti, c. mid-1640s, oil on canvas

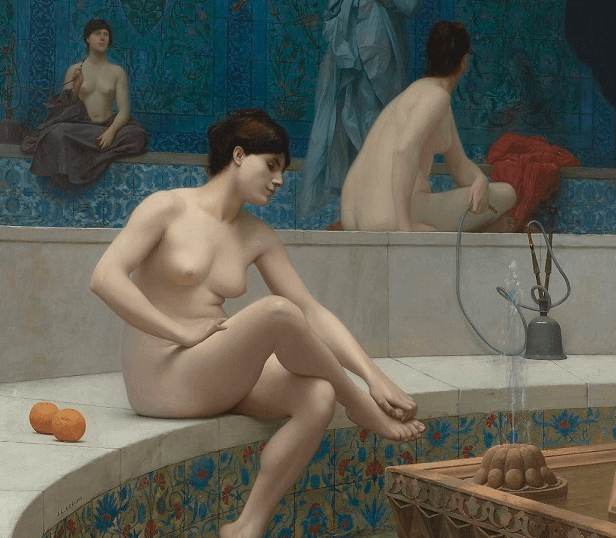

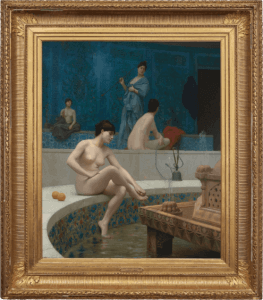

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Les Baigneuses du Harem, 1901, oil on canvas

In the 19th century, Jean-Léon Gérôme was undoubtedly one of the leading painters of the academic nude, and the theme of the harem had already been popularised by painters such as Delacroix and Ingres. Gérôme’s nude bathers are less lascivious – albeit no less sensual – than the odalisques of Ingres, and his reliance on photographs contributed a sense of accuracy to works such as Les Baigneuses du Harem (1901). In fact, they are artificial constructs: Gérôme would never have been permitted to sketch in a harem, and his model would therefore have been a Parisian girl – if you look closely you can see that the same model has posed for all four figures. Around the same time Gérôme painted his Baigneuses, Renoir executed his Jeune Femme Nue, a small-scale view of a seated young woman partially draped. This delicate, brilliantly-coloured work straddles the line between the traditional academic nude and the informality of the modern nude – though it stops short of attempting to shock the view in the manner of Manet’s Olympia.

Not all nudes are meant to be purely academic, of course; in some, the element of nakedness is emphasised for storytelling (or voyeuristic!) purposes. In Pier Leone Ghezzi’s Susannah and the Elders (late 1720s – early 1730s), we as viewers are complicit with the wicked elders, gazing lustfully at the naked Susannah. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, artists such as Auguste Rodin and his pupil Camille Claudel exploited the power of the naked form to communicate emotional as well as physical exposure and vulnerability. Claudel’s L’Implorante, petit modèle relates to the artist’s L’Age mûr, a monumental sculptural group depicting a man caught between old age and youth – but the figure of a nude young woman on her knees, imploring, carries an additional pathos as it was conceived during Claudel’s tumultuous (and ultimately tragic) relationship with Rodin. Meanwhile, Rodin’s own Petite Eve depicts the titular figure after the Fall, suddenly penitent as well as aware and ashamed of her own naked form. Similarly emotionally exposed are the three women in Picasso’s Trois nus (1938), a spiky, charged wartime drawing that may be based on the three women in the artist’s life: his estranged wife Olga, his long-term mistress Marie-Therèse, and his new love Dora Maar. By distorting the seemingly pleasurable scene of nude bathers, Picasso communicates a sense of unease and anxiety.

Pier Leone Ghezzi, Susannah and the Elders, late 1720s – early 1730s, oil on canvas

Camille Claudel, L’Implorante, petit modèle, conceived c. 1898 (cast by 1920), bronze with dark brown patina; and Auguste Rodin, Petite Eve, conceived in 1893 (cast by 1917), bronze with green-black patina

For full details and prices of any of the works cited, please contact [email protected].