Giovanni Paolo Panini – painter, architect, and designer of stage sets – was as much responsible for Grand Tourists’ images of Rome as his fellow countryman Canaletto was for romantic notions of La Serenissima. But how accurate were these depictions? Neither Canaletto nor Panini felt constrained by the rules of strict topographical fidelity, and both often blurred the boundary between landscape and capriccio (an imaginary view).

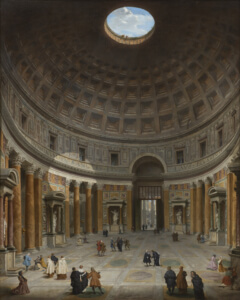

Giovanni Paolo Panini, Rome, the Pantheon, a view of the interior, 1734

But Panini’s views of the Pantheon – a subject so popular among collectors he painted at least eight known autograph variants, with even more studio versions known to exist – are among his most topographically faithful, presumably because the Pantheon required little in the way of imaginative embellishment; indeed, apart from the evolution in fashion, we might be looking at a painting of the building as it appears today. Let’s take a closer look at this most iconic of structures through the eyes of one of the greatest of the high Baroque painters of architecture.

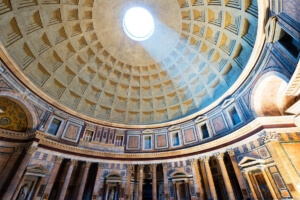

Interior of the Pantheon with the famous light ray from the top

The Pantheon was built as a Roman Temple, originally commissioned by Marcus Agrippa during the reign of Augustus (27 BC – 14 AD) and completed by the Emperor Hadrian. It was probably dedicated circa 126 AD. In 609, the Byzantine Emperor Phocas gave the building to Pope Boniface IV and it was consecrated on 13 May 609 as a Catholic church, the Basilica di Santa Maria ad Martyres – although it is also known colloquially as Santa Maria Rotonda for its shape.

Exterior of the Pantheon, end of the 19th century

Through Panini’s lens, the Pantheon stretches away from us as we look simultaneously in all directions, in a visual effect akin to what can be achieved with a wide-angle camera lens. We instinctively lean back and look up towards the oculus, our gesture echoed by the tiny figures craning to look up from Panini’s canvas. Straight ahead, we look through the entrance rotunda to the monolithic granite Corinthian columns supporting the portico. Looming above our heads is the coffered concrete dome, which remains – nearly two millennia after its construction – the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome. The bronze that originally lined its coffers was stripped away long before Panini’s time, sent to Constantinople by Emperor Constans II in July of 663 AD. More recently, just a century before Panini, Pope Urban VIII (1623-44) ordered the bronze ceiling of the portico melted down and repurposed for bombards for the Fortification of Castel Sant’Angelo; according to some sources, it also provided the bronze for Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s elaborate baldacchino in St. Peter’s basilica. In the centre of the dome, an oculus is open to the sky providing light and ventilation – and, for Panini’s two curious and fearless onlookers, a view of the events below.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Baldacchino di San Pietro, 1623-1634

One of the most impressive, and eye-catching, elements of the Pantheon’s interior – exquisitely captured by Panini, and highlighted by the spot of sunlight cast on the wall – is the intensely colourful array of building materials. Over the years, although the exterior of the Pantheon has been stripped of some of its embellishments – and apart from the bronze ceiling and monumental columns, which were once rare Egyptian porphyry – the interior has remained largely intact. The walls and floors are inlaid with stones including dark red porphyry from Egypt, Docimian marble from Asia Minor, Numidian yellow marble from Chemtou in former Carthaginian territory, grey granite, and green porphyry.

Detail of the floor

Since the Renaissance many important historical and artistic figures have been honoured with burial in the Pantheon. We can find the tombs of the artist Annibale Carracci, the composer Arcangelo Corelli, and the architect Baldassare Peruzzi – but perhaps most significant among them is Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, better known as Raphael, who died aged 37 in 1620. His tomb is located to the far right of where we stand in Panini’s view (positioned at the high altar, in fact), and the columns framing the tomb can just be seen at the far right of the painting. In what is surely no coincidence, Panini has signed and dated this work on the edge of Raphael’s tomb monument, in a bold effort to align himself with ones of the supreme Renaissance masters.

The tomb of Raphael, with the Madonna del Sasso by Lorenzo Lotti, also known as Lorenzetto