Associate Director Dr. Molly Dorkin talks about Robert Delaunay’s 1925 Painting “La Ville de Paris, La Femme et La Tour Eiffel”

Robert Delaunay’s towering work of Orphism, “La Ville de Paris, La Femme et La Tour Eiffel” is no stranger to public exhibition. Standing at a phenomenal 4.5 metres tall, the crown jewel in Delaunay’s Eiffel Tower series was first displayed at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes 1925 in Paris. It is both a wonderful depiction of ‘les annees folles’ (the roaring twenties) and the emerging visual concept of Art Deco (a term inspired by the same fair in Paris), a vibrant and colourful depiction of “la Tour Eiffel” and other Parisian landmarks. This video takes us back to 2015’s Masterpiece Fair in London, where the picture was shown by Dickinson in conjunction with works by Robert’s wife, Sonia Delaunay. It was also exhibited at TEFAF 2016, where it was one of the fair’s celebrated attractions. Associate Director and head of research at Dickinson, Dr. Molly Dorkin talks about the content and significance and provenance of the work in the film above.

“One of the earliest sketches he did of the Eiffel Tower,” says Dr. Dorkin “An oil study from 1909, was actually painted for his then fiancee Sonia Terk as an engagement present, so this helps us to understand why this was such a meaningful subject for her and why after Robert’s death in 1931 she held onto this painting for the rest of her life.”

As one of the founders of the Orphist movement, Delaunay’s work was at the cutting edge of artistic development in France during the early 20th Century. He was a master of colour and wrote extensively on the subject, arguing that colour was a thing in itself, with its own means of expression and form. He was aware of the pioneering work of the French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul, whose research was published in 1839 as De la loi du contraste simultane des couleurs. (The text was translated into English and published in 1854 under the title The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colors.) Specifically, Chevreul was investigating the optical properties of contrasting colours, and he identified the phenomenon by which the perceived colour of a particular hue is influenced by the colours that surround it. Unsurprisingly, his discovery had a tremendous influence on the work of artists such as Delaunay, who harnessed this new knowledge to achieve deliberate visual effects. Chevreul is one of 72 scientists and engineers whose names are inscribed on the Eiffel Tower, and one of only two who were still alive when Gustave Eiffel planted the tricolore, the national flag, at the apex of the Eiffel Tower on 31 March 1889.

Fascinated by this new Parisian landmark, Delaunay soon began a series of paintings and drawings known as his ‘Eiffel Tower Series’, the first of which was an engagement present to Sonia Terk, a textile designer who would become his wife, Sonia Delaunay. She later recalled: “It was ‘our’ picture. The Eiffel Tower and the Universe were one and the same to him.” After Robert Delaunay’s death in 1941, this work remained in Sonia Delaunay’s own collection until her death in 1979. It can be seen in various photographs of Sonia in her studio. A talented artist and designer in her own right, Sonia produced striking and original fabrics based on the aesthetics of Orphism, and she dressed Surrealists, socialites and film stars. She also designed interiors, and together with Robert was responsible for the set and costume designs for Le P’tit Parigot (“The Small Parisian One”. This 1926 French movie, shot as a serial in six parts, was directed by René Le Somptier and starring Georges Biscot. La Ville de Paris, la Femme et la Tour Eiffel can be seen in the background in contemporary photographs of the film set.

“The need for a new subject has inspired the poets, launching them onto a fresh path and bringing to their attention to poetry of la Tour [the Eiffel Tower], which communicates mysteriously with the whole world. Rays of light, waves of symphonic sounds. Factories, bridges, iron structures, airships, the numberless gyrations of aeroplanes, windows seen by crowd simultaneously” (R. Delaunay, originally published in Les Soirées de Paris, October 1913, p. 111).”

To the right of the Eiffel Tower, near the top of the canvas, is a round shape with thick, dark radiating lines. This represents the Place Charles de Gaulle, also called the Place de l’Étoile, the meeting point of twelve large avenues including the Champs-Élysées. At its centre we see the block-like arched shape of the Arc de Triomphe, one of the most famous monuments in Paris. It was commissioned in 1806 to honour Napoleon’s victory at Austerlitz. In 1919, three weeks after the victory parade celebrating the end of hostilities in World War I, Charles Godefroy flew his Nieuport biplane through the arch, with the event captured on film. It is this moment that Delaunay is evidently celebrating in his composition, and we can see the plane itself soaring skyward in the upper left corner of the painting. Godefroy’s achievement, much like the Eiffel Tower itself, symbolises the triumph of technology and modernity.

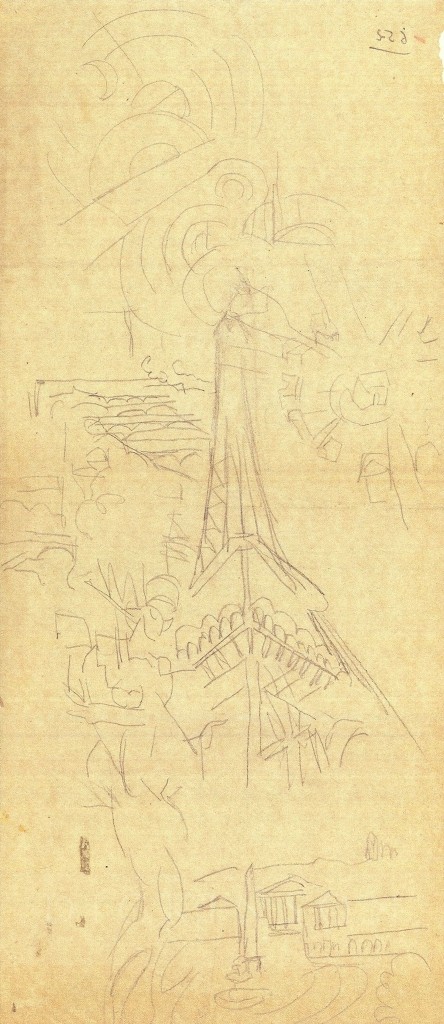

In addition to several pencil sketches in which he worked out his earliest ideas, Delaunay evidently painted two studies in preparation for his submission to the 1925 Exposition. Both are considerably smaller in scale. The more loosely painted of the two, now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, measures 130.8 x 31.7 cm. A second study, more detailed yet still smaller in scale than our painting, at 208 x 52 cm., was last recorded in a sale in Paris at the Palais Galliéra (8 Dec. 1966; see Apollo, April 1967, p. 312). There is also a painting entitled La Tour Eiffel et l’Avion, which shares the same measurements as the upper canvas of La Ville de Paris, la Femme et la Tour Eiffel, and may have been intended as an alternate top (previously Galerie Gmurzynska, Cologne).

When Delaunay declared “Art in Nature is rhythmic and has a horror of constraint”, he may have been thinking of the soaring height and repeated geometric patterns of his Eiffel Tower. The dizzying perspective, which seems to look simultaneously down at the Pont de la Concorde between our feet and up at the biplane soaring above the horizon, echoes the giddy pace of les années folles. Like the Eiffel Tower itself, Delaunay’s radical construction received its share of scepticism from conservative critics; yet it has endured to captivate contemporary audiences with its timeless celebration of technological advancement and human ambition in the modern metropolis.

“La Ville de Paris, La Femme et La Tour Eiffel” was named “Most Outstanding Picture” of the fair at Masterpiece 2015 and was a major attraction at TEFAF 2016, where it was exhibited by Dickinson.